IN THE EARLY SPRING LIGHT, the village of Nambé seems to secretly sigh, awaken, and then exhale the breath and promise of new life. Despite the obvious changes that contemporary life brings to many of the rural villages of New Mexico, it is evident that something unchanged, ancient, and timeless is about to reoccur.

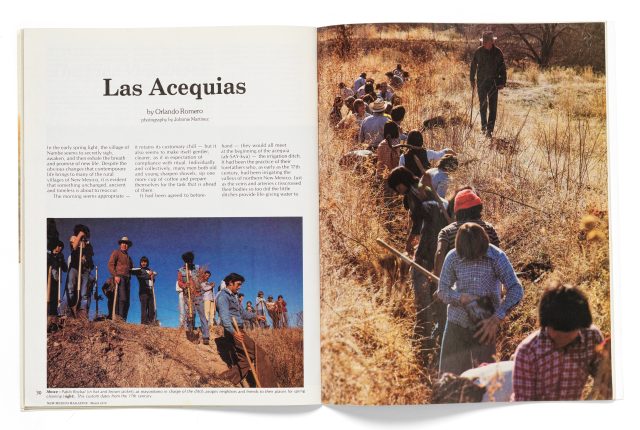

The morning seems appropriate—it retains its customary chill—but it also seems to make itself gentler, clearer, as if in expectation of compliance with ritual. Individually and collectively, many men both old and young sharpen shovels, sip one more cup of coffee and prepare themselves for the task that is ahead of them.

It had been agreed to beforehand—they would all meet at the beginning of the acequia (ah-SAY-kya)—the irrigation ditch. It had been the practice of their forefathers who, as early as the 17th century, had been irrigating the valleys of northern New Mexico. Just as the veins and arteries crisscrossed their bodies so too did the little ditches provide life-giving water to their thirsty fields. From this relation has grown a communal existence that is both physical and social. It doesn't matter if the ditch serves three families, 30 families, three acres or 300, the result is the same—physical and cultural survival is and always has been dependent upon the ditches.

As is the nature of anything that is ritualistic, a certain amount of ceremony accompanies that rite. There has to be someone in charge, someone who directs, someone who marks and calls out the various sections of the ditch and assigns workers to those sections and, of course, the many cleaners who will shave the acequia sides, scrape its bottom, burn the past summer’s weeds and chop the wandering roots that perpetually seek the acequia’s cool moisture.

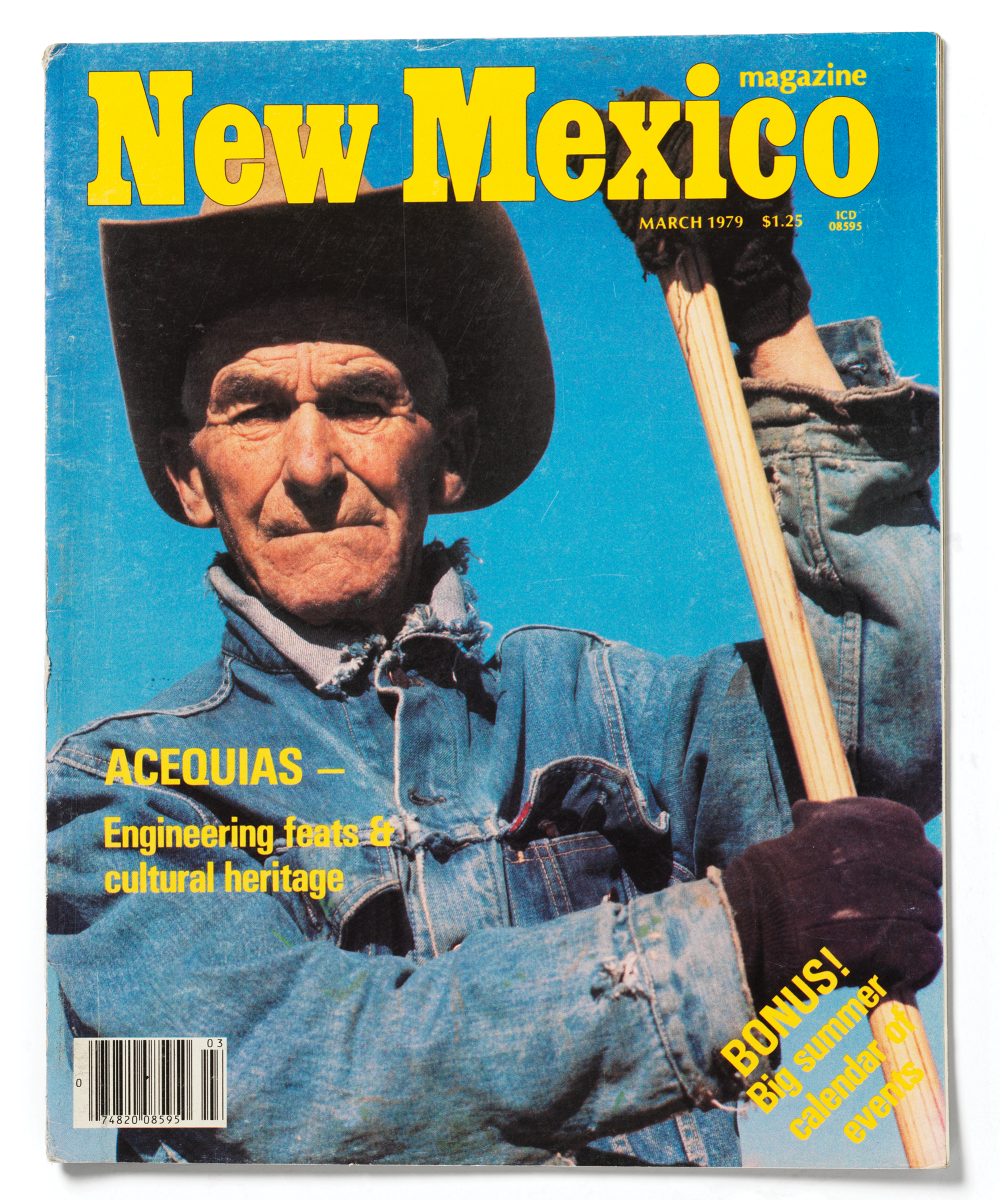

ON THE COVER

Bernardo Casados, in his eighties, carries on the time-honored tradition as rayador of the Nambé irrigation ditch. Photograph by Johnnie Martinez.

This particular acequia in Nambé meanders past ancient cottonwood trees, wild rosebushes, alfalfa fields, flowers to be, thorns, corrals, adobe houses, and horses that romp in an open field, glad to be relieved of their winter lethargy. All bring past memories to me of endless summer days to come. Somehow I couldn't picture my life on a piece of land without an acequia. My childhood and my contemporary manhood have been spent in activities revolving around the acequias—whether spreading manure on fields, pruning fruit trees and grapevines, ridding the pond of perpetual willows, hoeing gardens until the sun goes down, all early and present activities have been connected to the acequias.

And beyond that are those special memories of being close to ancient old people and relatives who would endlessly talk about the ways of growing things, how deep to plant the chile seed, when to irrigate it. Especially endearing are those recollections of my grandfather and me on summer nights irrigating the field of recently planted corn, the field that glowed magically under the influence of a full moon. The earth became wet and brown and from it rose an essence so particular to wet earth that to this day it is one of my most lingering of memories.

Read more: North of Santa Fe, a water mill continues a tradition and brings a community together.

Maybe it is because the acequias and all that accompanies them are even more ancient than the coming of the early Spanish colonists. According to Phil Lovato, in his work Las Acequias del Norte, ditches were already in use by the Puebloans when the Spanish people arrived. He adds that the Spanish colonists brought with them the experience and technology of irrigation and its institution as practiced in Spain during the period of the Moors. Whatever the historical reason, the feeling was genuine and primal. The maintenance of the ditches and their associations assured the individual and collective survival of village peoples.

So it is that the men gathered at Nambé have come to address themselves to the cleaning and maintenance of the ditches. As customary, the mayordomo begins the task of reading the names of the various members of this particular acequia. His authority, as described by the association’s bylaws, includes the responsibility for making payment to laborers who substitute for absent members. The next most important man is the rayador, whose responsibility is to mark the section assigned to each individual cleaner. If, for example, you are assigned the number five, as the rayador goes down the ditch rayando (marking numerically) that section as number five’s responsibility, you must clean, shave, and scrape that section.

QUOTABLE

“They are all ages, from little girls to men, and they are walking in the same direction. They come from Trampas, Santa Fe—the surrounding towns and villages. They are pilgrims journeying to a hallowed place. Every Good Friday and the Thursday night before, they create a living border along the roads that lead to the village of Chimayó.”

—from “Pilgrimage to a Hallowed Place,” by Scottie King

If there are 30 men working the acequia, then the assigned numbers run as high as 30. As soon as the last section is finished, the rayador begins the process of assigning sections numerically all over again until the ditch is cleaned and repaired. It also is a way of telling who needs to go back to his previously assigned section and complete his work if the mayordomo is not satisfied with the individual or his work. In some sections the ditch needs more work than usual or extensive repair has to be completed. The mayordomo then assigns a group of men to continue necessary repairs while the main crew proceeds with the usual cleaning.

Although the work is usually difficult, there is always occasion for conversation and socializing because time usually overlaps before the last section of the acequia is finished and the rayador marks off the new sections. For many of the men it is time to renew old village conversations, to talk a little about life or just plain village gossip. For many of us, it offers the opportunity to converse with village patriarchs like Don Bernardo Baca, who in his eighties not only still participates in the spring ritual of the acequias but also has a good story to tell about life in the village, usually about days when there was so much water that people had trouble crossing the small Nambé stream, or about days when there was so little water that it was a miracle plants produced anything at all. Whatever the conversation, there is always time to reflect on all the things that are close to or about the acequia. There is also the feeling of participation, of camaraderie, of renewing communal bonds.

Read more: The first chile feature by New Mexico Magazine describes the evolution of the chile.

Just a few years ago, a branch ditch needed repair. The acequia was used by four or five families and, therefore, was not one of the principal ditches that receives the usual spring attention. My grandfather and Don Bernardo decided to contact the local families involved, and in less than a few hours we received the help necessary to complete the cleaning. In addition, Don Bernardo volunteered a horse and, with a large scoop-type shovel attached to it, we managed to do collectively in a few hours’ time what would normally have necessitated days. Once again, the acequias had brought us together.

In many cases, however, disputes over how much water a person can use, or how long he can irrigate, or about a person who is caught irrigating when it is not his turn end up in a severe reprimand from the mayordomo, or, at worst, in a court of law. Because laws regarding the acequias go back more than a hundred years, the rights of users and their portions are fairly well established. It is, however, the responsibility of the mayordomo to ensure that individual users are not abusing existing laws of the local ditch association. So important is this responsibility that at least one law states that a mayordomo may be jailed if he does not fulfill the obligations of his office.

Because water is such a precious commodity in the Southwest, it is interesting to note that water disputes among members of local ditch associations are few in relation to the long history of acequia use.

The Report of the Special Committee of the United States Senate on the Irrigation and Reclamation of Arid Lands of 1890 includes the Compiled Laws of New Mexico regarding the acequias. Of particular interest is Section 26: “It shall be the duty of the overseers to superintend the repairs and excavation on said ditches or acequias; to apportion the persons or number of laborers furnished by the proprietors; to regulate them according to the quantity of land to be irrigated by each one from said ditch or acequia; to distribute or apportion the water in the proportion to which each one is entitled, according to the land cultivated by him, also taking into consideration the nature of the seed, crops, and plants cultivated, and to conduct and carry on said distribution with justice and impartiality.”

Whether or not the letter of the law was strictly adhered to, obviously the acequias mentioned in the report of 1890 not only determined the future growth of New Mexico but also existed in perpetuity before the arrival of the American government.

And it is manifest every spring that with each shovelful of damp earth the acequia laborers throw on the bank of the ditch, they too are part of the history-making process—that for this task, men of all ages gather to do what is necessary. And the land will respond by providing them with the rewards due them for their labor.

But, most important, the ritual of the acequias is one of the last links to the cultures that have nurtured New Mexico.

Sourdough Pancakes - Ann Edwards

SOURDOUGH: MAN & BREAD SOURDOUGH. Two things come to mind at the mention of the word: Mouth-watering breadstuffs and those tough prospectors of the West and Alaska. The men derived their name from the bread (or rather the leavening agent used in the bread, a fermented flour). The prospectors used to carry a start of sourdough with them into the wilderness.

The loss of his sourdough starter meant hardship to the prospector. He was known to walk miles through blizzards to get another start. Almost every meal depended on sourdough. It was used for bread, biscuits, pancakes.

The night before, or at least six hours before you want pancakes, place sourdough starter in a glass or ceramic bowl (never metal), and stir in:

1 cup lukewarm water (not hot)

2 cups flour (white or whole wheat)

2 tablespoons sugar

1 teaspoon baking soda dissolved in

1 tablespoon water

1 egg

1 teaspoon salt

2 tablespoons melted shortening

1. Let this stand in a warm place, loosely covered with a towel or wax paper, overnight.

2. In the morning, stir and remove ½ cup starter to your sourdough starter jar and place back in refrigerator to be used again.

3. To the rest of the batter, add:

- 1 teaspoon baking soda dissolved in

- 1 tablespoon water

4. Stir and add:

- 1 egg

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 2 tablespoons melted shortening

This makes a thin batter and very lacey pancakes full of flavor. Do not make big pancakes. A lot of small dollar-size

work better.