WITHIN A FEW DAYS OF ARRIVING in New Mexico’s Embudo Valley, my wife, RoseMary, and I were inspecting a rental property in the upper end of the narrow valley. It was an old adobe, sans bathroom or running water, but capacious.

A flimsy outhouse leaned in the backyard. Some 50 feet from the back porch, there was a narrow channel. I walked over to it through the dry grass and was astounded to see it brimming with water, flowing from east to west, slipping beneath an old apple tree and the barbed-wire fence that separated the property from the downstream neighbor’s. I was entranced. There is something magical about small watercourses wending their way through arid landscapes.

This was my first acequia. New to New Mexico, I didn’t even know the term then, was yet to learn that it was the Acequia del Medio, that it was one of nine in the five-mile-long valley, and that there were up to a thousand other acequias throughout the state. But when I peered down into its clear flow, I felt that, in some sense, I had come home. We lived there for two years before we were able to move into our own homemade adobe on the other side of the river, el otro lado, in an area known as El Bosque and served by the Acequia del Bosque.

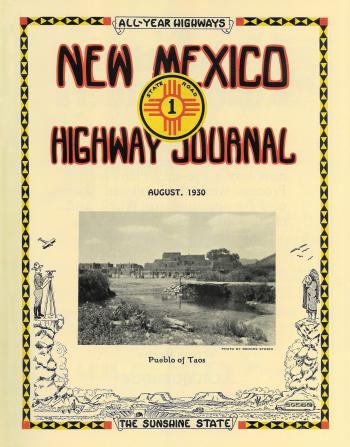

ON THE COVER

August 1930

A photo of Taos Pueblo by Brooks Studio was featured alongside John Galleon’s “Stories of the Taos People.”

I had many more things to learn about acequias. One was that they are governed by a commission made up of three landowner members of the acequia. The actual work of maintaining the ditch and managing the water is done by a mayordomo or mayordoma. In these terms, one touches on the rich cultural and geographical history of the acequia tradition. Acequia is an Arabic term, pointing to North African origins; mayordomo is from the Latin majordomo, meaning head of household.

Acequia traditions were brought to New Mexico during the Spanish conquest, taking root in the land alongside, and perhaps aided by, similar traditions practiced by Pueblo people. But most of the terms are Spanish: comisionados/as, or commissioners; parciantes, or member-owners; la limpia or la saca, the cleaning and digging out of the acequia. The word itself is two-pronged in meaning: acequia can refer to the physical irrigation ditch or to its governing structure.

Acequias are unusual in many respects. They are among the oldest engineered structures, in a vernacular sense, in continuous operation on the continent. They are maintained through communal labor, both volunteer and modestly paid. Their democratic organization, which has flown under the radar of numerous absolutist regimes, controls a basic resource: water, which is rare.

The mayordomo is responsible for checking the water flow once the acequia is cleaned. Mayordomo José Luis Aragon walks the entirety of the ditch to assure there is unimpeded delivery. Photo by Sharon Stewart. Copyright Sharon Stewart 1992–2003. Part of El Cerrito y La Acequia Madre Collection, accn. #2003-014. Used here with permission.

Serious lessons in acequia culture began for me when I was elected commissioner in the mid-1970s. I was at first mistakenly flattered by what I took as appreciation of … what, my organizational skills? The reality was that acequias can also mean families feuding over who gets, or doesn’t get, water during dry times. I was probably elected in the hope that I might side with one of the feuding families.

The function of the commission is to oversee the mayordomo and to collect money from parciantes to deal with acequia expenses and pay the mayordomía, the mayordomo’s monthly salary. Only commissioners get an exemption from ditch dues. So we would all climb in a car and go andando collectando whenever the ditch treasury needed money, leaning particularly on those who had serious delincuencias. This was my way—as tax collector—of integrating myself into my adopted and largely Hispanic community.

The Acequia del Bosque, on the north side of the valley, is often the first to conduct the limpia, which is overseen by the mayordomo, who marks out sections, also known as tareas (tasks or chores), for the workers to dig with a stick or shovel (pala). Tareas are usually six to eight feet in length, enough room for workers, peones, to shovel without banging into each other. A pion is also a form of measure. My property of about two acres is rated at one pion, meaning I must supply one worker, or the cash equivalent, to the acequia for every day worked, which in turn determines how many hours of water I can use during times of rationing. It also determines the amount of mayordomía I pay.

Acequia culture is part of the soul of New Mexico. Acequias feed countless backyard and market gardens, orchards, and pastures. They were also a source of drinking and washing water. These ancient waterways not only have remained an embodiment of the traditions of the earliest Hispanic colonists, but they also have enriched the lives of newcomers who embrace these systems. For me, the acequia has been a mentor, imparting lessons about water, labor, and community. It has turned neighbors into collaborators and friends. Above all, the acequia has rooted me to the patch of land I have called home for the past 50 years.

Every year, when the water begins flowing again in the acequia, in late March or early April, I know that all will be well, that winter is over, spring is here, and summer is coming.

Stanley Crawford, a farmer in Dixon, is the author of several books, including Mayordomo: Chronicle of an Acequia in Northern New Mexico.