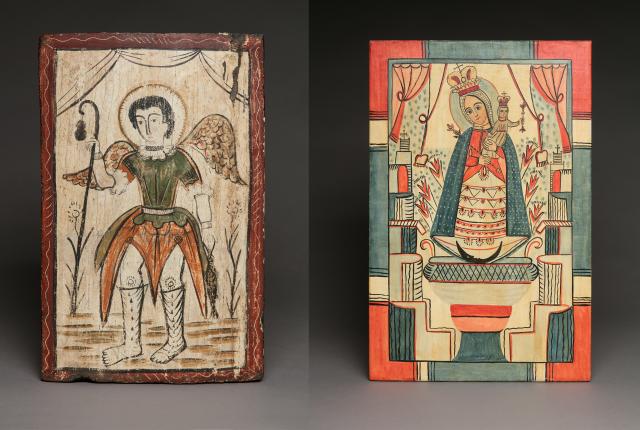

THE ART OF THE SANTERO, or maker of saintly images, is believed to have begun around 1760 in colonial New Mexico. Franciscan priests, charged with the task of establishing Christianity on the frontier, worked with local artisans to provide the holy images needed for worship and decoration in the newly built adobe churches. The santeros made retablos, painted images on hand-adzed pine panels, and carved three-dimensional bultos, both of which were then gessoed and painted with native pigments.

Most of us Santa Fe santeros did not grow up seeing old santos in our churches, since most were decorated with large plaster-of-paris figures depicting Saint Joseph or Saint Anthony. My first introduction to the older images was the result of a survey of northern New Mexican churches in the late 1980s, when photographer Jack Parsons and I documented the historic santero art. At the time, I felt the radiant beauty of the faces on some of these bultos was certainly reminiscent of a woman’s touch: perfectly arched eyebrows, well-formed lashes and lips, a touch of cheek color. Ah, one could only wonder.

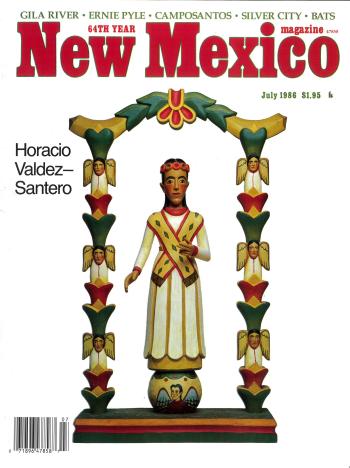

ON THE COVER

July 1986

Master santero Horacio Valdez’s Inmaculada Concepción was photographed by Mark Nohl.

Although researchers have no evidence that women participated in the creation of this art during the colonial period, it certainly became a reality in the 1970s in Santa Fe. During that decade, several women became santeras, including my late sister Anita Romero Jones, Monica Halford, and Gloria Lopez Cordova. I, too, began to follow in the footsteps of the 19th-century artists by establishing myself as a saint maker, a career that would follow me for almost half a century. Today there is an impressive number of women artists who are honored to carry that title.

Before I was a santera, I worked as a legal secretary. I had never considered becoming an artist, and my transformation came about quite serendipitously. After being away for seven years, I returned to my birthplace of Santa Fe. For almost a decade, my parents, Emilio and Senaida Romero, had been well-known tinsmiths, working out of their home. In their own way, they helped to reestablish that traditional art, joined later by two of my brothers, Bobby and Jimmy Romero.

After assisting them at the annual Spanish Market that year, I tried my hand at painting retablos, experimenting with acrylics and then watercolor paints. I went from being somewhat of a copyist, relying on published photos and museum collections, to developing my own style, which was far more colorful than those of earlier artists. My greatest influences were the collections of the Museum of International Folk Art and the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, along with the Larry Frank collection, all of which I was fortunate to have explored many times. I look back on some of my early paintings and I can see the progression from a somewhat primitive style to something a bit more refined. As the years passed, my art became my full-time occupation. Early on, I noticed that most of the woodcarvers and retablo painters were men; women were outnumbered ten to one. It was heartening to see, little by little, these numbers changing every year at Spanish Market. Eventually the ratio evened out.

I received commissions to create large altar screens for churches at El Rito, Ojo Caliente, Arroyo Hondo, and other communities in northern New Mexico. Perhaps the highlight of my career was being chosen to create 15 painted panels of the Stations of the Cross for Santa Fe’s Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi in 1997. As a local artist and as a woman, to be commissioned to create art that was destined to remain in situ for generations to come was mind-boggling. These stations have now been viewed by tens of thousands of visitors.

That someone might find peace and comfort in viewing my work was always far more important to me than whether it was “pretty” or “well done.” I am particularly fond of the 12th station, in which I chose to honor my family by incorporating the names of my ancestors, my parents, my siblings and their families, and my children and grandchildren. What appears to be white lace on Mary’s veil actually contains a prayer for myself and for all who enter the cathedral. The prayer is written in Spanish, and although it is not visible from the aisles, I know it is there.

The art of the santero is an important part of New Mexico’s traditions and central to the spirituality of many New Mexicans. Over the years, other local churches have embraced santero art, to the delight of both visitors and parishioners. Through my efforts and those of other women artists who continue to perpetuate the art, I believe we honor not only our city but also our families and those young artists who hopefully will follow in our footsteps. It is a tradition worth keeping alive, cultivating, and bringing into the public light.

Read more: The author of Abandoned New Mexico finds meaning in our oft-forgotten places.

Marie Romero Cash is a book author and folk artist based in Santa Fe.

WE HAVE ALWAYS CREATED ART

“Places like the Wheelwright have been integral in creating connections with Native American artists. In the 1930s, the Studio School program at the Santa Fe Indian School created masters of contemporary Native art. Indigenous artists work to protect our collective memory through their creativity and their agency. New Mexicans and the Indigenous people have always made objects that reflect their narrative and their worldview—and they’ve always created art.”

—Andrea Hanley (Navajo), chief curator, the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian