PORTER SWENTZELL, TRIBAL SECRETARY FOR SANTA CLARA PUEBLO and executive director of Kha’p’o Community School, admits that he isn’t an expert in turquoise. Some of Swentzell’s earliest memories are of watching members of the community earn a living by working in pottery and sculpture, not jewelry. He earned a doctorate in justice studies and served as assistant professor and department chair of Indigenous liberal studies at the Institute of American Indian Arts, in Santa Fe. When it comes to the story of turquoise in New Mexico, the scholar has found that there is simply more beyond the blue than meets the eye.

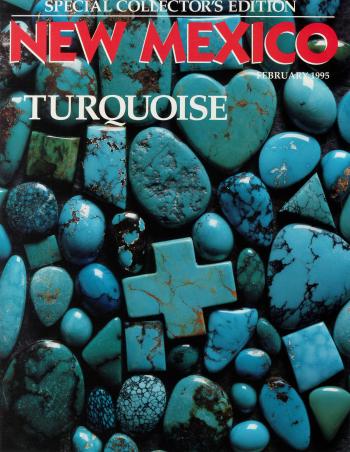

ON THE COVER

January 1995

Mark Nohl photographed various types of treated and untreated turquoise for this collector’s issue.

THERE WAS ALWAYS CLAY AROUND. It was a way of life. I didn’t know many people who had a nine-to-five job. We’re not a pueblo known for jewelry, but we utilize it in our traditional activities. Native artists sell their products for their livelihood, but in our community there is also a demand for those things. We are the major consumers of our own art.

My family had two or three turquoise necklaces growing up. They were precious. Turquoise was hard to get. As a family, we had to share the turquoise for ceremonies. I think my mom, Roxanne Swentzell, traded her artwork as a sculptor for it. People would get things through trading and exchange, which is still common today.

Going back a thousand years to Chaco Canyon, even earlier, think of the natural environment. Turquoise was spectacular. It’s bright, it’s vibrant. A rock may not seem that special to us now, but a thousand years ago it was as special as can be.

When the Spanish invaders came into New Mexico, they were looking for a city of gold. They found turquoise, and they were disappointed that the people had only “Turkish” rock. From the Spanish perspective, turquoise had no value or meaning.

I think it’s ironic. The Spanish didn’t see it in the 16th century, but turquoise became a major product for tourists to buy through the curio trade. Turquoise increased in value over materials that were historically more difficult for Native artists to obtain.

For example, there is no ocean here. Native jewelers in the Southwest often used seashell, spiny oyster, and coral, but that had to come from far away. Those materials were held in high esteem, but people don’t think about it in the same way now.

My wife is from the Santo Domingo Pueblo. When we got married, many of the gifts that were given to me were necklaces.

We had nothing. We received enough to equip my kids. Now I can say to my kids, “Oh, which necklace do you want to carry tomorrow?” They don’t have to share like my household did growing up.

My favorite kind of jewelry is shell necklaces inlaid with turquoise. That way, it’s black, white, and blue on top of the shell itself.

BE JEWELED

Mine these spots for Native-made turquoise jewelry and more.

Palace of the Governors, Santa Fe. Porter Swentzell always takes visitors to walk the line of artists selling handcrafted wares under the portal. “You can engage with the artist directly,” he says. “Your money goes to the person who made your jewelry.” nmmag.us/portal

Gallup Trading Company, Gallup. Dubbed the Biggest Little Store in Gallup, this shop lives up to its nickname when you walk through its adobe facade to discover glass cases stuffed to the brim with handmade turquoise treasures. galluptrading.com

Winfield Trading Company, Vanderwagen. Call ahead for an appointment at this family-owned store specializing in turquoise and offering at least eight varieties of hand-cut cabochons. Ask to see the vault. winfieldtradingcompany.com