COOL BREEZES DRIFTED INTO THE BEDROOM this morning, where the drapes swayed slightly—a hint of impending rain hung in the air. The scents of lilac blooms and cedar and juniper trees drifted inside, immersing us in early-morning sounds and the promise of a beautiful day.

Later, on my morning walk, tiny lizards skittered across my path. One paused to regard me before darting off into the brush. Then a thin rabbit scampered out from under a cedar tree, leaving small dust clouds fluttering as it leaped over weeds and between rocks. Two tiny red birds landed on a branch. As I neared them, they flew ahead and landed on a piñon tree. I talked to them, calling them “little ones” or “sweeties” in Navajo, as I would my grandchildren. This exchange continued for a while—they seemed to wait for me each time they lit on trees alongside the trail.

Doves cooed nearby, reminding me of my childhood at our cabin in the Carrizo Mountains, west of Shiprock. My father would say, “Hasbídí aní, the doves are talking.” We would pause and listen. He taught us to be observant and to pay attention to everything around us.

Decades later, such memories still sustain me. Public utilities were unavailable in Shiprock during the 1950s and ’60s, when I grew up in a multigenerational household. We lived on a farm surrounded by cousins, uncles, aunts, and elder relatives. We saw our cousins as siblings and our aunts and uncles as “our little fathers” or “little mothers.” Elders were grandparents.

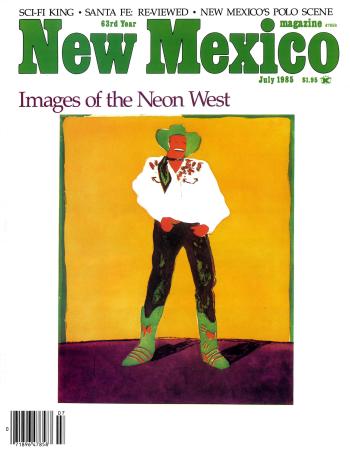

ON THE COVER

July 1985

Fritz Scholder’s Hollywood Cowboy in Roma graced the cover for a story on artists making the Wild West chic.

We called everyone by relation, and our siblings by nicknames. We didn’t know we had “official” or “white” names. This resulted in some memorable stories. Little Sister insisted in kindergarten that her name was Nimasi (Potato), not Marilynn. We siblings were called to verify that she was indeed Marilynn, while Nimasi burst into tears! We consoled her before returning to our classrooms.

Daily life consisted of prayers, age-appropriate farm and household tasks, songs for the animals, and meals that included sharing stories, jokes, teasing, and laughing. The adults told stories, songs, and jokes that were woven into everyday tasks. We learned ceremonial protocol, how to talk respectfully, and our relatives demonstrated compassion and optimism with a sense of humor.

They told us that our primordial deity, Changing Woman, created us. We are her descendants, who live now as Earth Surface People, protected above by our father, the sky, and supported by our mother, the Earth. Changing Woman bound the first four clans to various locations in Diné Bikéyah, Navajo Country. Thus we are matrilineal people, and my clans, Tódik'ozhí (Salt Water People) and Tódích'íi'nii (Bitter Water People), are associated with distinct places and with specific animals as our protectors.

They said that we are made of prayers, stories, and songs, and that the Diyin Dine'é, the Holy Ones, are sentient in plants, birds, animals, and all living things.

Our sacred mountain in the east, Hesperus Peak, is visible from our home, as is the Shiprock pinnacle, to the west. Shiprock seems to be at the edge of our fields; she is our guardian, because she saved our ancestors from a flood centuries ago. We see her daily in the distance, sometimes draped in snow, other times glistening with rain, enveloped in clouds of mist. Her sharp outline was most often distinct against the vast blue sky. She takes on muted hues throughout the day: a pale mix of pink and yellow at dawn, a dark blue-purple at midday, and layers of light red, soft blue, and pink streaks at dusk. Up close, the jagged peaks are dark brown, then drift into a mix of coral, beige, and gray.

Our teachings are memorialized by the concept of saad, which is the guiding knowledge or wisdom in the songs, prayers, stories, and teachings. Although saad was given to us at the beginning of Navajo time, it is relevant today. It is said that the Holy Ones knew we would face challenges in this present glittering world. Saad lives on in us, helps us face threats, and, most importantly, urges us to remember all we’ve been taught and to impart this knowledge to our children and grandchildren. It reinforces our relationships and responsibilities to one another and the land.

These gentle teachings of my parents’, siblings’, and relatives’ stories became the literary inspirations that led to my being appointed the first poet laureate of the Navajo Nation in 2013. I honor their lives and the love they bestowed on me.

Then as now, the smell of rain always fills us with gratitude. On clear afternoons, we can see the misty slants of rain and billowing clouds approaching from the west. Then the air becomes saturated with the scents of fresh wet dirt and damp juniper and piñon trees. This is how we know that the Holy Ones remember us.

Luci Tapahonso is professor emerita of creative writing at the University of New Mexico.

Read more: Climb aboard the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad for a trip you’ll never forget.

OUR OUTDOOR COOKING IS FIRE

“Part of Pueblo culture and tradition, the horno has been used for cooking and baking for centuries. The concept was brought over by the Spaniards, who taught Pueblo women how to build, maintain, and use the outdoor, beehive ovens made of adobe. Today they’re used throughout the pueblos of New Mexico to bake bread, Indian pies, and cookies and to roast our corn and meat. I use cedar or juniper, because the smokiness adds to the flavor.”

—Norma Naranjo, owner of the Feasting Place, which offers classes at Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo