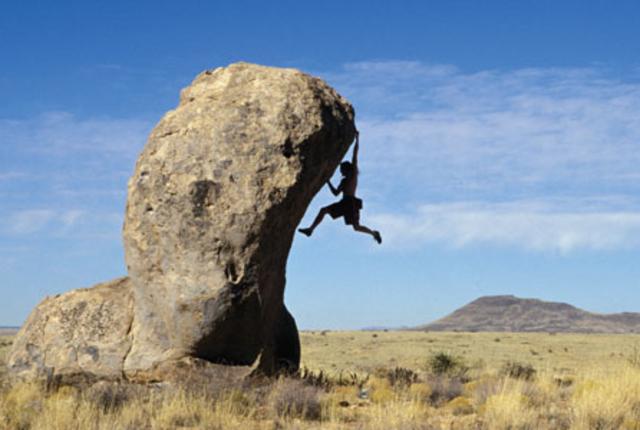

Above: Fairfield grabs an overhang at City of Rocks,

which must have been purpose-built for boldering.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY: MICHAEL CLARK

JUST EAST OF ALBUQUERQUE, a patch of bus-size, globular granite boulders stand sentry in the Sandía Mountain foothills. Nearly every rock climber in New Mexico knows them as U-Mound. If car racers have empty stretches of highway and basketball players have blacktop, rock climbers have U-Mound—a place to gather, mingle, give beta (as in advice), and show off.

In the mid-1980s, U-Mound lured a mix of traditional rock climbers sharpening their skills on the shorter, more accessible stones and an emerging breed of scalers who wanted nothing more than to contort themselves up small stretches of granite—“problems,” as climbers call them— with few graspable features. Among these boulderers was a high school student named Timy Fairfield. He had the cocky swagger and buzzy energy of a rocker, combined with the athleticism of a competitive skier and an elite soccer player. Lithe, wiry, and compact, he sported über-eighties hair that he says “varied between Billy Idol, Flock of Seagulls, and a mohawk.” In a sport of rebels, Fairfield cranked up the revolution by climbing while his boom box blasted bands like Fugazi, Agent Orange, and Guns N’ Roses.

If the other climbers were bothered by the music and attitude, they admired the kid’s talent. Fairfield defied any classical notions of vertical climbing. He moved up by going every other direction. Thanks to his strength, he could hang low by his shoulders and then leap high. Sometimes his feet swung in front of the rest of his body and he looked like a crazed acrobat. Bottom line: He was getting good and distinguishing himself among the best climbers in Albuquerque. Before his teenage years were over, this homegrown phenom would beat nationally ranked climbers and start eyeing the best of the best, an ocean away in Europe and Russia.

Born in 1969 in New Jersey, Timy (pronounced “Timmy”) Fairfield was a toddler when his mother, Lucinda, moved him and his younger brother, Thomas, to New Mexico. Soon she married Steve Fairfield, who helped raise the two boys while she worked as a waitress and at hotels. Meanwhile, she put herself through school and used her education to found a financial planning firm. “That’s probably where I get my drive, from my mother,” says Fairfield.

Almost immediately, their uncle, Raymond Holland, already living in Albuquerque, introduced the Fairfield boys to the New Mexico wilderness. The Coast Guard veteran took the boys hiking in the Sandías and taught them the fundamentals of outdoorsmanship. One of the trips gave 11-year-old Timy an idea. “I remember the first time I rappelled down a cliff,” he says. “I was looking at the features and decided I wanted to climb because it seemed like it would be a lot more challenging to climb up than to go down.”

In 1980, it was an uphill journey merely to find opportunities to climb. The sport had yet to achieve the popularity and acceptance it enjoys today, when even families with young children flock to indoor climbing walls. Fairfield was forced to be a little creative to get out of the house and on the rocks. “It was like ditching school to go surf,” he says. “No one wanted you doing it, but the less they wanted you to do it, the more you wanted to do it. The first thing I learned was how to sneak out.”

He told his parents he was going hiking, but he was really climbing with his uncle. During these covert trips to the Sandías, Fairfield mastered the fundamentals of traditional climbing with ropes, harnesses, carabiners, and anchors.

When he wasn’t climbing, Fairfield skied and played soccer. Skiing was something of a family sport, and his parents pushed him to take it seriously by joining the Junior Ski Patrol at Sandía. It didn’t stick. “By the time I got through the first-aid training I decided I didn’t want to be on the ski patrol, because I had more of a robber mentality than a cop mentality,” Fairfield says. “I wanted to be the one raising hell and being chased, not the one enforcing rules.”

But even anarchists need a cookbook. In the mid-1980s, Fairfield’s parents got wise to his climbing and figured he might as well learn to do it smartly and safely. They sent him for a week of instruction at the International Alpine Academy in Eldorado Springs, Colorado, where he learned from accomplished alpinist Charlie Fowler. A year later, at 16, Fairfield traveled to Europe while a student at Albuquerque’s Sandia High School. “I was exposed to a lot of artificial climbing walls, especially in France, Germany, and England, and that was fun,” he says. In his element, climbing next to Europeans, Fairfield noticed their gymnastic techniques, which included fluid movement, high flexibility, and multi-directional approaches. The method was cutting- edge and used by only a handful of athletes in a growing segment of the climbing sport that frequently coincided with “bouldering.”

Since the early days of alpinism in the 19th century, climbing was inseparable from exploring and mountaineering. Vertical athletes in California’s Yosemite National Park changed the game in the 1950s and ’60s by setting their sights not on mountain peaks, but sheer walls of granite. Boulderers went a step further by climbing even shorter rocks—perhaps 20 to 30 feet tall. Their goal was to find paths up the most absurd stones using strength, agility, and power. “In ’86, I started bouldering, and at that time it was considered practice for real climbing. It hadn’t really defined itself as an athletic discipline,” says Fairfield.

To get stronger, he adopted a few unusual procedures, some pioneered out of his garage. “My friends and I would bolt pieces of two-by-four to the wall and handles to the ceiling in our parents’ garages to simulate climbing,” he says. He also worked out with gymnasts to simulate the kinds of moves he could make on the rock. Many of these innovations he kept to himself. He still does. “The millennials are more about collaboration, but I’m a Gen Xer. I came out of the Cold War. If you develop a training technique, you keep it secret as long as you can,” he says.

The word on bouldering and gymnastic-style climbing, however, was not a secret. Some climbing historians credit Ameri-can John Gill with popularizing, if not inventing, the discipline of bouldering in the 1950s. Gill was a professor of mathematics who brought a keen mind and acrobatic aesthetics to climbing. (It’s not a coincidence that bouldering routes are called problems just like math equations are.) Fairfield followed Gill’s example and moved to Fort Collins, where he attended Colorado State University and spent his free time gripping granite.

Joe Crotty, a climbing companion and former world-class tennis player, took note of Fairfield’s abilities and suggested in 1988 that it might be time for him to compete at an open. Until then, Fairfield had climbed as a largely spiritual exercise. He hadn’t really thought about professional prospects. “Joe convinced me to compete when I was 19, and I did well, I placed second,” he says. He won that spot by beating a handful of nationally ranked climbers. Even so, it didn’t put him on the map.

But in 1988, there wasn’t exactly a map on which Fairfield could be plotted. Competitions in the United States existed mostly on a regional level, and only a few could be classified as national events. If there was a proving ground for American climbers, it was the wall at the Cliff Lodge at Utah’s Snowbird Resort. A good performance there could elevate any climber’s pedigree. In 1991, just three years after his first competition, Fairfield grabbed national attention on that outdoor wall. Other victories soon followed. “When you’re really having a great day,” he says, “you wish the finish line was farther.”

His newfound success catapulted him into an elite field of American climbers. With that, Fairfield gazed overseas. He wanted to prove himself in the more established European field against the strongest climbers in the world. The Russians had been staging competitions as far back as the 1940s. Both the organized sport and its athletes outpaced their American counterparts. But on his initial forays into Europe, Fairfield fell as low as 70th place. He knew the only way to get better was to make the full-time move to Europe and learn from the continent’s masters. The European lifestyle and the ability to travel agreed with Fairfield. He liked living in France, but his skills suffered in comparison with those of his new rivals. Still, he stuck with it. Sometimes, he says, you have to “walk out to the end of the plank and figure out how to swim.”

Even so, he was getting close to drowning. Fairfield routinely placed toward the bottom of the pack at World Cup and other European contests. The events, the climbing equivalent of international track meets, demanded that athletes demonstrate a variety of skills in a handful of separate climbing categories. Fairfield was humbled. Ranked as one of the top climbers in North America, he had reason to believe that he might lose his sponsors and his whole way of living. Stuck at the bottom looking up, he “damn near gave up” and “was just burned out. It was really tough.”

When he got done sulking, he decided to take some action. Fairfield accepted a spur-of-the-moment invitation to the 1995 indoor Speed Climbing World Cup in Birmingham, England, the night before the event. Much to his surprise and that of his competitors, he logged victories in head-to-head matchups and in the overall speed competition. He found a method of cutting across the artificial climbing wall that left his legs free, giving him something of a shortcut and saving time—a technique he used to beat the undefeated defending world champion from Russia in the final round. The win changed Fairfield’s fortunes entirely. He had an incentive to train harder and muscle his way up the European talent pool. In hindsight, he says, “It’s all right to be put on your back a little bit.” Within three years he had begun regularly placing in the top ten at international events, distinguishing himself as one of the few Americans to make a name in European climbing.

Birmingham renewed his career, and in 1998 the International Council for Climbing Competition added bouldering to the circuit as its own event. The generalist nature of previous meets had frustrated Fairfield. “You didn’t really know what you were training for,” he says, comparing it to a decathlon with no advance warning of events. “You know you’re running the 400 meter, so you train for the 400. But you might have to knock out the long jump and, 10 minutes later, knock out a mile.” The security of training specifically for bouldering gave Fairfield confidence. He posted the best results of his career over the next seven years, placing in the top three at the World Cup. In January 2005, Urban Climber magazine declared, “Timy Fairfield is one of the great competition climbing and bouldering legends of our time.”

Between 2004 and 2005, Fairfield transitioned out of competition and into route setting—mapping the courses for other climbers—for ESPN and the Outdoor Life Network. In a way, planning these televised events placed even more pressure on him. If Fairfield created a bad route, it could ruin the contest. He also had to stay in shape to anticipate the skills of the newest waves of athletes. Even now, Fairfield is so strong that last year, at age 46, he recorded a V15 difficulty boulder problem—akin to a sub-10-second 100-yard sprint. Only the best climbers in the world could hope to replicate that feat, and most of them are 10 to 20 years younger than Fairfield.

These experiences, coupled with a lifetime of climbing, led Fairfield to coaching and advising from his base in Albuquerque. His Futurist Climbing Consultants helps a growing number of indoor climbing gyms customize their walls for everyone from professional athletes to families at play. Work is under way on a new commercial climbing gym in Albuquerque. He also advises California-based Mad Rock Climbing on shoes designed specifically for his type of climbing.

Climbing took Fairfield to more than 40 countries across the world, but he keeps his home in Albuquerque. At his most successful and at his most troubled, Fairfield always found solace and motivation in New Mexico. He and his wife, fellow champion climber Brandi Proffitt, built an exercise facility in their backyard and an improvised climbing gym in their garage. Recently, the couple purchased a tract of land near Taos, where they hope to carve out a base camp to explore new climbs in northern New Mexico. They pondered “retiring” in other areas, but gravitated back to New Mexico, where Fairfield learned his craft. Here, when his feet hit the rock, he knows precisely where he is.

—Jason Strykowski is featured in “Storytellers."

ROCK ABILITY

New Mexico is peppered with great spots for climbing, many within easy driving distance of cities. While some of these locations are great for beginning climbers, novices should get training first. Some spots are appropriate for boulderers with minimal equipment such as “crash pads” (reinforced mats that cushion climbers from the ground on short climbs) and specialty climbing shoes. Others require ropes and protection. Helmets are always advisable.

The great indoors may be the best place to get started. New Mexico has two climbing gyms that offer introductory classes and opportunities to meet other climbers. In Albuquerque, Stone Age Climbing boasts New Mexico’s largest artificial wall. The Santa Fe Climbing Center hosts an active group of regulars. Both offer memberships and daily climbing.

For outdoor instruction, contact the New Mexico Mountain Club. The New Mexico Bouldering guidebook provides details on a thousand specific climbs.

DIABLO CANYON

WHERE: Santa Fe

BEST FOR: Intermediate climbers

TYPE OF ROCK: Basalt

WHY: The canyon offers dozens of routes in a relatively compact area. Many climbs are cleaned and bolted, making them perfect for sport climbing.

GETTING THERE: From NM 599, take the Camino La Tierra exit south 5 miles to Old Buckman Road. This dirt road reaches the canyon’s mouth, where most climbers park.

QUESTA DOME

WHERE: Taos area

BEST FOR: Traditional climbers and boulderers

TYPE OF ROCK: Granite

WHY: Questa Dome is peppered with traditional climbs that require advanced climbing ability and technical expertise needed to place cams, or anchors, in seams along the rock. A boulder field leading to the dome has a number of problems more suitable for early-stage climbers.

GETTING THERE: Head north from Taos on NM 522. Drive 6 miles past Questa and go right at El Rito on County Road B042. Turn right where the pavement ends. After 1 mile, the road reaches a junction. Turn right and look for parking at the trailhead.

CITY OF ROCKS STATE PARK

WHERE: Deming

BEST FOR: Intermediate boulderers and hikers

TYPES OF ROCK: Welded rhyolite and welded tuff

WHY: Boulders pop up like mushrooms at this otherworldly location. Walking between them can be adventure enough, but many of the rocks can be climbed. Roped climbing is not allowed.

GETTING THERE: From Deming, go north on US 180 for 24 miles, then northeast on NM 61 for 3 miles. Turn left into the park.

THE BOX RECREATION AREA

WHERE: Socorro

BEST FOR: Intermediate sport climbing

TYPES OF ROCK: Andesite, rhyolite, and welded tuff

WHY: Five rock walls line this canyon. Each offers a selection of bolted routes perfect for sport climbers. Boulderers happily explore the lower sections of rock.

GETTING THERE: From Socorro, take US 60 west for 7 miles to Box Canyon Road.

ENCHANTED TOWER

WHERE: Datil

BEST FOR: All climbing levels, from beginning to advanced

TYPE OF ROCK: Welded tuff

WHY: The walls are filled with opportunities for roped sport climbing. Dozens of routes make this a popular and social spot for climbers.

GETTING THERE: Take US 60 west from Datil for 6 miles. Turn right on Forest Road 6; stay on the rocky dirt road for almost 3 miles to Forest Road 59, which reaches the climbs.

ROY

WHERE: Roy (30 minutes east of Wagon Mound)

BEST FOR: Intermediate to advanced climbers

TYPE OF ROCK: Dakota sandstone

WHY: A large network of canyons is filled with thousands of boulders composed of the best-quality rock of any sandstone in the Southwest. A lifetime of bouldering opportunities await. GETTING THERE: From NM 39 at Mills, take Mills Canyon Rd. west to Mills Canyon. From here consult the guidebook to find the various access roads that take you to the dozen or so bouldering trailheads.

Above: Keenan Takahashi tackles a problem in the Ortega Mountains of northern NM.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY: ERIC BISSELL

THE ORTEGAS

WHERE: Carson National Forest

BEST FOR: Beginning to advanced climbers

TYPE OF ROCK: Quartzite Why: The beautiful swirled quartzite is bullet hard and gives amazing, finger-intensive boulder problems that are begging to be climbed. The views aren’t bad either!

GETTING THERE: The Ortega Mountains have more than a dozen bouldering areas. One of the most popular is called Nosos (pictured), located three miles north of the village of La Madera on NM 111. Either park at the pullout on the left and hike up or, if you have a high-clearance vehicle, follow the dirt road FR 121 for .7 miles, take a right, then follow this to the trailhead.

U-MOUND

WHERE: Albuquerque

BEST FOR: Beginning to advanced boulderers

TYPE OF ROCK: Granite

WHY: A popular and convenient bouldering spot; Timy Fairfield honed his technique here while in high school. A plethora of outcroppings suit different levels of climbers.

GETTING THERE: In the Sandía Mountains foothills. Take Tramway Blvd. to Copper Ave. and head east for half a mile.

Want more like this? Subscribe now!