I came from a yoga mecca—southern California, where there are too many classes and kinds of yoga to choose from. Which is fine if you practice twice a day, seven days a week.

When I moved to Roswell from Irvine, I was newly certified to teach yoga and wanted to teach and write. In Roswell, I found a new world of yoga: students who ride horses and have farms and ranches. And others, like me, who are transplants from another faraway city.

But Roswell is no yoga mecca. People practice occasionally or a few times a week, in a studio, in private lessons, at the gym, or at the senior center. But they’re hard-pressed to find the perfect class every day of the week. Where’s my tribe? I wondered. Where is the group I see and practice with daily? I learned to practice at home.

As a teacher, I observed a community of yoga practitioners different from the kind I knew. It was characteristically Roswell. In a new class attended by 20 women, I asked about previous injuries and heard this answer three times: I broke my pelvis once. What? How? Riding a horse. Rather, by being thrown from a horse. They didn’t think twice about the answer, and didn’t want me worrying over it. Ah, it’s an old injury. A wave of the hand. These were not strained hamstrings from playing hoops, or injuries from running too often on pavement year after year. These were shoulder injuries from lifting too much hay.

I started to ask other questions: How much does a bale of hay weigh? How many cows are you taking care of? How’s it going with that new horse? What is barrel racing? What’s the difference between English and Western riding? I was not only a new yoga teacher; I was a city girl with a lot to learn about this place.

And when I started teaching at my own studio, my culture shock became even more pronounced. My early-morning class was filled with people who had animals: dogs, horses, and barnyard cats. I overheard talk about watering and feeding and caretaking. How to keep creatures warm or cool. A few students changed their yoga schedule entirely during harvest. And last year, when I invited teachers from Colorado to teach a workshop, a few students couldn’t attend because they were shooting firearms at a marksmanship competition.

California may be on the West Coast, but this is the West.

Roswell is famous for aliens, and it may have once boasted that it was the dairy capital of the Southwest—as the sign says when you drive in from the north on U.S. 285 onto Main Street—but it is also still a small city far from other cities. However, it doesn’t matter what you do for a living: lawyer, farmer, soldier, writer, rancher, petroleum landman, teacher. Yoga has the same effect everywhere: It makes people feel better in ways that they had not thought they could. And yoga sometimes changes people’s lives. It’s been amazing to me to see a young student decide to change career paths, and another—who’s building a house—design a space in her dream home just for practicing yoga.

It may be that 24/7 yoga classes are not in Roswell’s future. There is much to be done. Up before dawn, horses to ride, cows to raise, land to care for. There’s a narrow window of time for yoga, given how the springtime wind skews the day here at the edge of the high plains.

But in Roswell, there’s also this: I show up to teach a yoga class and get invited to learn to ride a horse. I learn how to shoot a pistol at a target. A student brings me a dozen eggs and says, Each one of these came from happy hens. I see one new student come into the studio and watch the others—each and every one of them—introduce themselves and welcome that person.

These things don’t happen in the big city. So yoga is changing my life again, too. I’m still from California. I miss chanting and 90-minute classes with wall-to-wall yogis. But this yoga community is kind, and Roswell has taught me an openness that the mecca couldn’t.

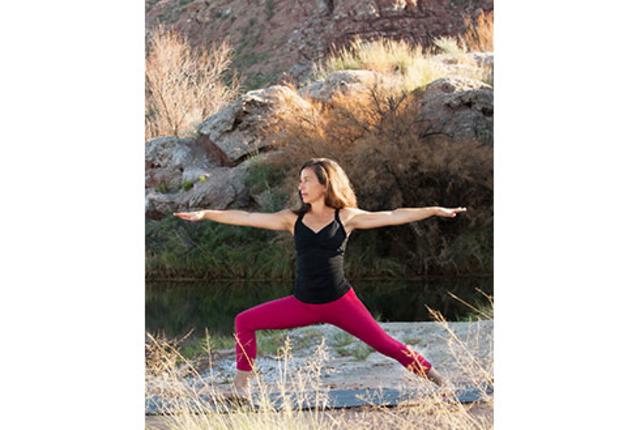

Colette LaBouff is the author of Mean, a book of prose poems. She teaches yoga in Roswell. Find out more a colettespeeryoga.squarespace.com.