Sculptor Debra Fritts and artist Frank Shelton in their Art Chapel.

NOT MANY ART ADVENTURES begin with what sounds like spy talk: Meet me under the pink flamingo at Bode’s. That’s the starting point for about half of the tours run by Abiquiú Art Project: an incongruously large sculpture in the parking lot of the rural village’s combo mercantile-deli-gift-shop-and-gas-station. (Others meet at the Abiquiú Inn.) A notable meet-up point matters. Once everyone’s introduced, they motor out onto country lanes that most tourists have never driven, where they meet museum-caliber artists whom most New Mexicans have never heard of.

“We’re more than a tour; we’re a cultural attraction,” says founder Teresa Toole. “It used to be Abiquiú was US 84 and everything you could see from it. Now people are getting off the main street and learning how people live out here.”

Thanks to Toole and the carefully curated artists on her by-appointment-only tours, visitors get a deep understanding of the region’s power over creative souls in the era after Georgia O’Keeffe, the patron saint of Southwestern sunsets, gigantic flowers, and bleached animal skulls. More than 11,000 admirers still visit the painter’s Abiquiú home and studio each year. Others take plein air painting courses at nearby Ghost Ranch, her summer digs. Her reputation as the mother of American Modernism has only intensified in the years since her 1986 death. The rugged geology, pristine skies, and historical culture that once inspired her now attract artists as diverse as Doug Coffin, a crafter of 30-foot-tall tribal totems, and Joseph Hall, a creator of intricate conceptual jewelry—with painters, photographers, ceramists, and sculptors scattered in between.

Toole, an otherwise retired escapee from the Seattle area (she’s also married to Hall), takes small groups of visitors on voyages into the studios of what she calls “the musketeers” to learn more about their processes, their backgrounds, and their pieces—and maybe even to buy some art. She matches her infectious enthusiasm with enough knowledge that, sometimes, she can finish the artists’ sentences—a great skill for those rare times when one of them isn’t available. Most of all, she’s committed to the magic that happens when visitors meet artists on their home turf.

“If it’s too many people,” she says, “they can’t get up close and personal to it. My whole point is to bring people to art made by artists in this rural place, in its habitat.”

Tempted? Let’s meet at the pink flamingo.

TWO ATTENTION-CRAVING DOGS will greet you well before Walter W. Nelson emerges from his casita-cum-studio, within barking distance of Bode’s. Give the pooches a pat, then pause on the porch to take in the big view of red mountains that serve as Nelson’s morning muse. “Pretty much the only thing to do is art,” he says, referring to both the visual motivation and his relatively Spartan digs.

After a globe-trotting career as an award-winning commercial photographer, Nelson heard the siren song of art. Besides shooting intensely detailed landscapes, the Texas native has branched out into sculpture, painting, and a blend of all of the above. Large-format photos grace a table, while one wall bursts forth with three-dimensional painting-sculpture hybrids that somehow evoke both Diego Rivera’s murals and Spanish Colonial bultos. Brilliantly colored minimalist paintings of ocotillo plants take up two other walls. The fourth carries a series of paintings about O’Keeffe’s beloved Black Place, near Chaco Canyon, which he reinterpreted by grinding that area’s black earth into pigment.

The New Mexico Museum of Art, in Santa Fe, and the Dallas Museum of Art are just two of the institutions that collect his work, which also explores soulful places in Australia, Europe, Latin America, and elsewhere. After decades of bouncing between Houston, New York, Santa Fe, and Abiquiú, he committed himself to the village in 2009. It’s a far cry from the go-go energy he was accustomed to, which was one reason he agreed to be part of the Abiquiú Art Project.

“I want to connect with a larger audience,” he says. “That’s not easy living in Abiquiú. Normally, it’s pretty quiet in here, and when you’re really locked in to a piece, you don’t want to talk to anybody.”

Some visitors bring out the gab in the artists, Toole says as the group heads to the next stop. Others are content to wander through, admire the work, and move on. The full tour can last anywhere from two to three hours, although she also tailors it to specific tastes. Far more than her handful of artists dot the region, and most welcome visitors during the annual Abiquiú Studio Tour, this year October 6–8, one of the oldest and most robust of such tours in the state. Toole thought it important to curate a more manageable, year-round tour with time for personal connections. If demand grows, she says, other artists will land within her net.

Stop number two sits off a long dirt road that briefly parallels the Chama River and passes a couple of historic estates. There, a husband-and-wife duo, painter Frank Shelton and ceramist Debra Fritts, share studio space in a neatly renovated WPA-era chicken coop. Their highly individualistic approaches blend in what they call the Art Chapel, next door. It’s a bright new building where her sculptures of otherworldly people (usually women) share the earthy palette and fierce rawness of his abstract paintings and effigies.

Walter W. Nelson fills his studio with art and dogs.

Walter W. Nelson fills his studio with art and dogs.

Shelton happens to be away on our hastily planned tour day. (He’s a volunteer guide at O’Keeffe’s home.) Fritts stands before his worktable, explaining the meanings behind the various pieces of drop cloth and collage parts—newspaper, tape, plaster, concrete, paint, and inks. Some of his pieces feature grids with intersecting points that he drills out, then sometimes fills but often leaves empty—commentaries on lucky encounters and missed opportunities. “He puts a lot of information in, then edits it down to a quietness,” Fritts says. “He works very intuitively.”

Her own works are similarly elemental, though born of one material: clay. Primordial beings with ghostly eyes rise around her. Birds pop out of a wall. A new series of ceramic shot glasses await a sip. Celebrated by places such as New York’s American Craft Museum (now the Museum of Arts and Design) and the Society of Arts and Crafts, in Boston, Fritts built her name in part on a unique way of glazing her pieces.

“Because I started as a painter, and I didn’t know better, I started mixing glazes like a painter would,” she says. Besides achieving faint hues that mimicked those on antique bisque dolls, she sprayed the glazes with water so they would drip down into the deeper earth tones anchoring each one’s body to the soil. Now she teaches others such techniques in weeklong workshops that sell out almost as quickly as she can post them on her website.

The couple spent years in the South before turning their vacation love for New Mexico into an Abiquiú home, which then altered their art. “I’m starting to rub dry clay powders from Ghost Ranch onto the clay to make a different surface,” she says. “There’s an earthiness here, plus the history and the combining of cultures. We’re going slower and being more thoughtful.”

THREE ARTISTS IN, Toole knows her guests could use a head-clearing break. Fortunately, the final two artists, Coffin and Hall, live across a lane from each other, and the end of their road offers a spectacular view of the White Place, or Plaza Blanca. O’Keeffe adored painting the sweeping drama of those sandstone cliffs. Toole indulges awed visitors as they grab more than a few smartphone snaps.

Then it’s on to Coffin’s studio, which Toole calls “the Meow Wolf of Abiquiú.” Stuffed from the floor to the high ceiling with art assemblages, works in progress, and commentaries on the state of Native American life today, it represents creativity on steroids. Of Potawatomie/Creek roots, Coffin grew up in Lawrence, Kansas, feeling what he calls “an apartness.” He developed his own set of symbols to portray his roots, most obviously in abstract totem sculptures, one of which towers at the Drury Plaza Hotel, in Santa Fe. Others have traveled to Paris, Saudi Arabia, and Africa, and a few bedeck the grounds outside his studio.

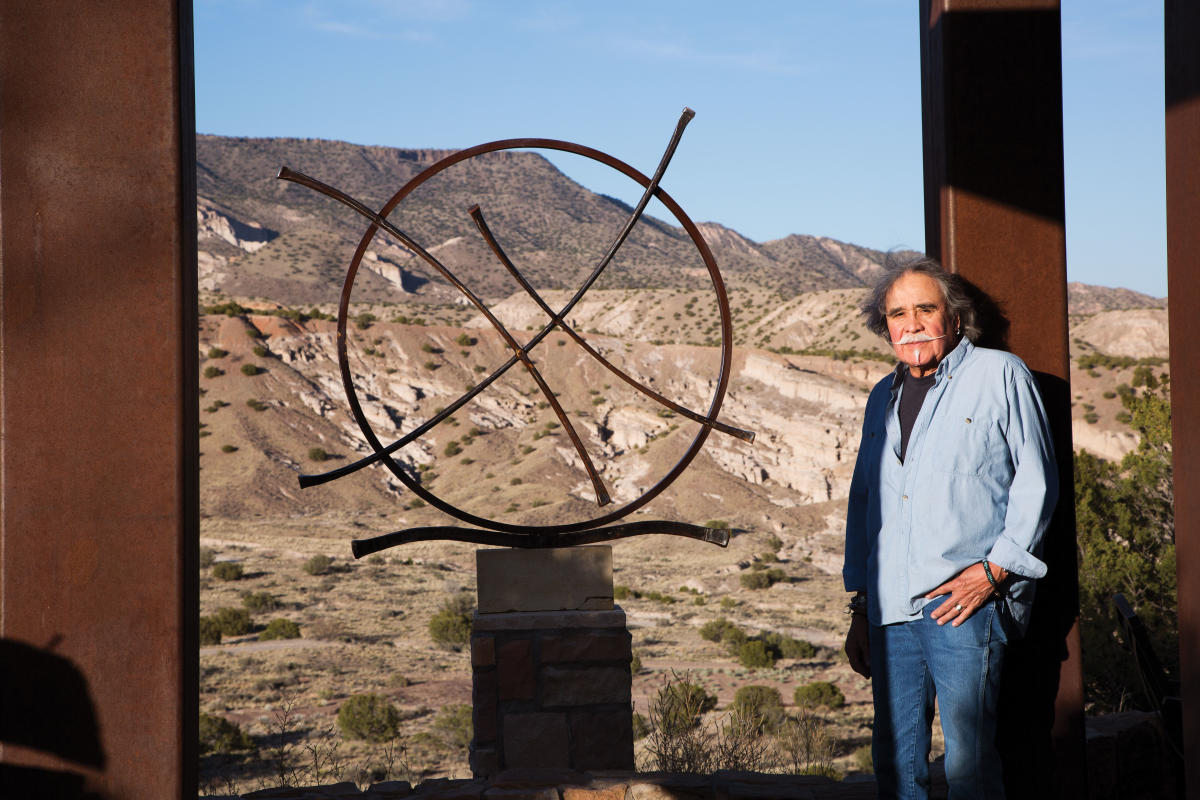

Doug Coffin stands by one of his totems and its inspiring backdrop.

Doug Coffin stands by one of his totems and its inspiring backdrop.

Inside, a cigar-store Indian bears a TV for a face. On the screen? A John Wayne Western. Pee-wee Herman dolls beam down on the chaos of buffalo heads, a heart sprouting antlers, maquettes of totem poles, abstract paintings, shields, and dice. “You get to see all the ideas of the artist,” Toole says, “which makes you understand the work better.”

Coffin got called to Kansas City, where he’s working on a long-held dream to craft a 30-totem installation. (A few weeks later, I run into him over lunch at the Abiquiú Inn. It’s that kind of town. I mention missing him at his studio, and he issues a blanket invite to return anytime. It’s that kind of town, too.)

After Toole’s guided tour of every part of his studio—including a bathroom bedecked with autographed photos of the Hollywood stars he knows—we walk over to Hall’s studio. He steps away from his jeweler’s bench to offer us homemade cookies and explain how he started his metallurgic career by inventing ways to control the rainbow of colors you can burn onto metals—tricks that elevated him into something of a star in international jewelry circles. Since then, he’s mastered tabletop sculptures, brooches that mix fine gems with found rocks, and a ring with movable parts that cast an eclipse-like shadow.

“Normal artists create a vocabulary and stick with that, but I found I do two or three pieces of a series and I’m on to something else,” he says. His gold-with-tantalum-inlay wedding bands, though, proved so popular that he’s made them for 35 years, and they’re worn as far away as Antarctica.

As we’re bundling back in the car, Toole mentions that she just gave a tour to a family from France—one indication of her extending reach. “Almost every person who’s gone with us says they feel that they understand Abiquiú itself better because they see how the artists relate to it and express it in their work,” she says. US 84 awaits our dust-speckled windshield, but in the rearview mirror, Abiquiú and its artists deliver a knowing wink. They know that we’ll be back.

THE ART OF ABIQUIÚ

Getting There

US 84 connects a series of small villages that make up Abiquiú. Head north from Española or south from Chama.

Artful

The Abiquiú Art Project offers tours at $50 a person for one to three people; $25 a person for four or more, 505-685-0504.

More than 80 artists open their studios 10 a.m.–5 p.m., October 6–8 for the Abiquiú Studio Tour. The self-guided event celebrates its 25th anniversary this year.

The just opened Georgia O’Keeffe Welcome Center holds a small exhibit about the groundbreaking artist and organizes tours of her home and studio Tuesday through Saturday, March 6–November 21. Tickets start at $30, 21120 US 84, 505-946-1000.

Ghost Ranch takes visitors on bus and horseback tours of O’Keeffe’s painting sites. You can also pay a $5 day-use fee to hike there. Youth and adult retreats and workshops include archaeology, arts and crafts, writing, and meditation, 877-804-4678.

Settle In

The Abiquiú Inn, next to the O’Keeffe Welcome Center, combines well-appointed casitas with a restaurant, gift shop, and gallery featuring local artists, 21120 US 84, 505-685-4378.

No visit to Abiquiú is complete without popping into Bode’s General Store for a green chile cheeseburger, locally made crafts, and camping supplies, from basics to Yeti coolers (21196 US 84, 505-685-4422.