Above: The Bank of the West Tower, nicknamed the Horizon Pillar, in Albuquerque. Photographs by Krysta Jabczenski.

THE SUN GLEAMS OFF the gild-ed bands of a white tower as Thea Haver, founder of Modern Albuquerque, leads me through the city’s Highland Business District and a few blocks of old Route 66. Oddly situated at the corner of San Mateo Boulevard and Central Avenue, the 17-story skyscraper juts above its surrounding single-story buildings. When it was completed in 1963, the First National Bank East was the tallest building in New Mexico—so big, in fact, that the state Department of Transportation reportedly filed complaints about the structure. Drivers cruising by, it’s said, caused accidents while craning to count its floors. Iconic even now, and still the tallest building outside of the downtown corridor, the building inspired contractors to nickname it “Horizon Pillar.”

Clad in something like 2.5 million one-inch gold tiles that reflect the brilliance of the desert sun, the building is a “monument to the optimism of this period,” as Haver puts it. That period is mid-century modern—a roughly 25-year interval between 1950 and 1975 when Albuquerque mushroomed from 96,815 people to 288,710. All those people needed houses, schools, stores, and office buildings. Modernist architects like Max Flatow, Jason Moore, George Pearl, Dale Bellamah, and W.C. Kruger responded with materials made possible by the newly engineered mass-production capacities of the factory age. Those architects, along with others, essentially created the Northeast Heights, marching out from the UNM area toward the foothills of Sandia Peak.

With styles that critics sometimes derided as boxy, cold, and downright ugly, their modernist feats now ride a nostalgia-fueled wave of popularity, fed in part by 21st-century cravings for a simpler-is-better design ethos. Ethan Aronson, Haver’s cofounder in a year-old business that celebrates modernism, slyly describes the style as “post–World War II, pre–Star Wars.” Together, Haver and Aronson are putting Albuquerque’s modern architecture on the map by conducting original research on standout specimens and sharing their histories through walking tours and special events that hold appeal for anyone who adores reruns of The Jetsons and Mad Men, Eames chairs, and coffee tables with hairpin legs.

Above: The entrance of the Horizon Pillar.

Above: The entrance of the Horizon Pillar.

In a long navy coat, knee-high brown leather boots, and big, dark sunglasses, Haver is as stylish as you’d expect an architecturally savvy 34-year-old to be. She extends a gloved hand to note how the basket weave of Horizon Pillar’s gold stripes and white concrete columns creatively minimize heat inside the building while also allowing it to meld into its environs by reflecting magical pink sunsets and the bluish grays of monsoon storms.

Now the Bank of the West Building, it’s a literally shining example of modernist architecture. The architectural firm of Flatow, Moore, Bryan & Fairburn used innovative principles to organize the structure, with the columns cast in place to support an elevator system at the building’s core. Inside, an open-floor concept dominates its 196,232 square feet. Envisioned as the hub of a five-block commercial complex that was never fully realized, it speaks to postwar aspirations crafted with industrial materials, organic shapes, a sense of futurism, and a “form follows function” philosophy.

Mid-mod design took off with the birth of the atomic age and then the Cold War. People flocked to the rapidly developing Sunbelt cities—in Albuquerque, to support the expansion of Kirtland Air Force Base and Sandia National Laboratories. Aronson’s own grandfather was a mathematician who moved from Connecticut to Albuquerque after receiving a call to work on the Manhattan Project. The 32-year-old’s family has been here ever since.

Above: The God's House Church in Albuquerque.

Above: The God's House Church in Albuquerque.

A Baltimore native and relative newcomer who landed in Albuquerque in 2014, Haver was surprised by the diversity of buildings she saw in a region more typically known for Spanish Pueblo Revival and Territorial Revival architecture. “There were a lot of architects coming to New Mexico who weren’t invested in the prevailing traditions,” she says. “They weren’t looking to the past for influences; they were thinking about the future.”

The pair started with a foundational document, (“our bible,” they say), produced for the City of Albuquerque Planning Department in 2013 by William Dodge and Cara McCulloch. Its 112 pages catalog modernist structures, but Haver and Aronson soon noticed how much it had missed. They estimate that the document captured about 60 percent of the midcentury buildings in Albuquerque, but even before the inception of their small company, the duo found more—and then more. “I think that was the spark that led us to starting Modern Albuquerque—noticing a limited awareness of Albuquerque’s recent past,” Haver says.

Read more: Rediscover Las Vegas. The Meadow City is more than the small town that we all love.

What excited them most was that the evidence remains. This is history you can touch. As we stand outside the low-slung Bank of America on Central Avenue, near its intersection with Washington Street, Haver shows me iPad pictures of what the original building looked like back when it was the Albuquerque National Bank. Designed by Kruger in 1959, the bank still wears its original dust-colored ashlar corners. Haver asks me to imagine where its large picture windows, now covered in brick, once were. A little closer to the present-day entrance, she directs my eyes to the rose-colored granite, almost unnoticeable underfoot, that was part of the original swank walkway.

The physical record of this time—even in tiny details—holds value for Haver and Aronson. They describe the work that they do at Modern Albuquerque as “preservation adjacent.” Through research, documentation, and hyping of Albuquerque’s abundant midcentury architecture, they have become publicists for the past.

On their walking tours, they guide the curious along a two-mile out-and-back stretch of the Highland Business District, a particularly dense neighborhood for modernism. Along the way, they reveal Albuquerque’s history through architectural details—a boomerang roof here, a wall of breeze blocks there. They offer two 90-minute tours: the classic Hairpin Legs iteration and the Retro Risqué, an adults-only dive into the more indelicate side of the era, complete with true tales of fallout shelters, tiki culture, and midcentury scandals. Always, the goal is to offer a different take on Albuquerque and build support for the architecture of yesteryear.

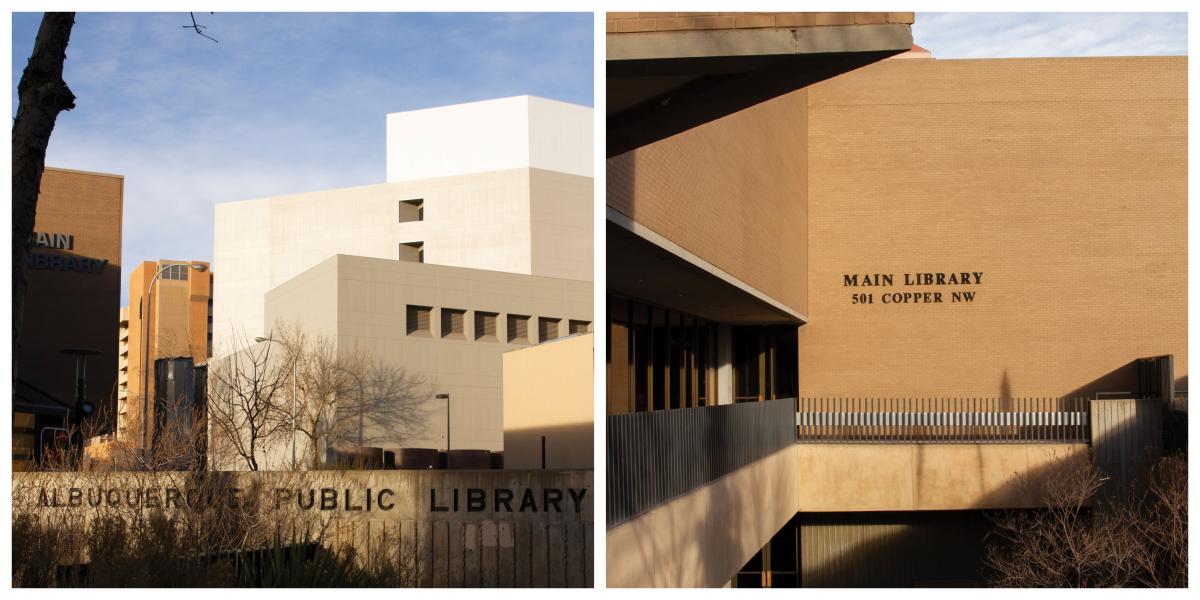

Above: The Main Library in Albuquerque's downtown.

Above: The Main Library in Albuquerque's downtown.

“These buildings can’t speak,” Haver says, “especially if they’re tucked back on side streets or escape notice in neighborhoods. If we’re not calling attention to their stories, they get lost.”

For Aronson, the buildings are more than just a critical part of Albuquerque’s history. He enthuses about the concept of “adaptive reuse,” the idea that such structures can be transformed to meet new and even more modern needs. Look at El Vado, Haver suggests. Once a bustling Route 66 motel west of Old Town, it fell into disrepair for more than a decade before developers renovated the space into a complex with a coffee shop, taproom, restaurant, quirky galleries, and newfangled accommodations that reopened in 2018.

“The best buildings,” Aronson says, “are not just boxes with four walls to keep us and our stuff out of the weather. They leave an impression on us, they make us feel something when we’re inside them.” Even better, he says, “they’re one of the few pieces of art that we can live inside.”

Love New Mexico? So do we. Subscribe today for just $3 an issue and we'll deliver our award-winning monthly magazine right to your door.

GET MOD

Modern Albuquerque’s website, offers resources for midcentury experts and newbies alike. Sign up for its monthly e-newsletter as well as upcoming workshops and special events. Check out @modernalbuquerque, its Instagram page, where the company shares discoveries, research, and all the right photo angles on our modernist past.

At Retrograde Tours get info on mid-century modern walking tours across Albuquerque. Each one costs $24 a person. The flagship outing is the Hairpin Legs Tour, a primer on Albuquerque’s modernist past, with plenty of room for customization. People 21 and older can scour Albuquerque’s bygone underbelly on the Retro Risqué walking tour.

MUST-SEE MODERNISM

First National Bank East

5301 Central Ave. NE

Designed in 1963 by Flatow, Moore, Bryan & Fairburn, this 212-foot skyscraper sits among single-story homes and businesses. Now the Bank of the West Building, it sports gold tiles and white concrete that reflect the desert’s atmospheric skies. Added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979, this building is not only a must-see; it’s quite hard to miss.

Main Public Library

501 Copper Ave. NW

A knockout brutalist design in the heart of downtown, this concrete structure opened in 1975. Architectural firm Stevens, Mallory, Pearl & Campbell designed it after visiting 50 of the most prominent libraries in the country. As journalist V. B. Price wrote, “It is at once a stately, friendly, and imaginative building with no pretentions or fears.”

Classic Century Square

4616 Central Ave. SE

Comprising nearly an entire wall of glass, the facade of what once was White’s Department Store is as stunning as the massive original staircase inside. This Flatow & Moore building was designed in 1957 to accommodate the needs of the burgeoning suburban sprawl. Haver conjures the aspirational spell it must have cast on drivers cruising Route 66. “Imagine it lit up at night, with all those shiny new appliances in the windows,” she says. Today it’s the Classic Century Square antiques mall, where sharp-eyed shoppers can score mid-century furniture and decor.

God’s House Church

2335 Wyoming Blvd. NE

Built originally to serve parishioners of the since moved Hoffmantown Baptist Church, this six-building complex was completed in 1965 after a 15-year construction. The main sanctuary’s east wall sports relief patterns punctuated by small stained-glass windows. That wall extends to meet a towering white concrete bell tower.