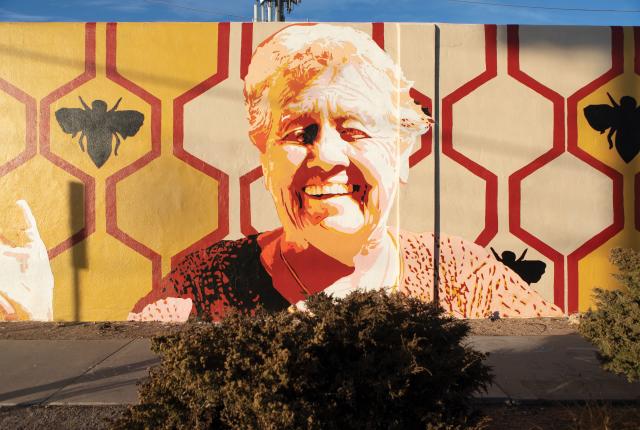

A MURAL NEAR MY OLD APARTMENT in Albuquerque, at the power substation on Silver Avenue and Cornell Drive, constantly gets tagged. Painted in colors of marigold and honey brown, it features images of pedestrians and cyclists in Nob Hill, with a smiling elderly woman in the central panel. Artist Mark Horst painted Honey in the Heart about a year ago. Now I see somebody cleaning off fresh spray paint almost every time I walk by it. These acts of addition and subtraction have, in my mind, become a part of the mural’s life cycle. Though I doubt it’s a part the artist intended, artworks are particularly vulnerable on city streets. The public will have its say.

All across Albuquerque, the cityscape abounds with public art—murals, sculptures, and temporary and permanent installations, some commissioned by the city, others created without anyone’s approval. The city has one of the oldest public art programs in the nation, having commissioned or purchased a staggering 1,000 pieces in the past 41 years. They range from neon sculptures to decorative highway overpasses to a tile-encrusted 1954 Chevy hoisted on a pedestal. Many have become treasured landmarks made by and for a specific neighborhood, roadside creations that give passersby pause, and memorials that reckon with (or gloss over) unsettling local histories. Their meanings are never static and, in some cases, highly contested.

“So much public art is just out there on its own,” says Sherri Brueggemann, manager of the Public Art Urban Enhancement Division of Albuquerque. “It’s like standing on some corner. You know, people just encounter it. We don’t have a docents’ program to tell everybody how to think about it. But that’s what public art is.”This year, Brueggemann’s program will let artists turn utility boxes all across the city into their canvases. No rules. No strings attached. “We know there’s going to be controversy about this,” she says. “But it’s going to be an opportunity to really explore how our city either supports and embraces art and artists or not—and how artists kind of sort themselves out.”

FRIENDS OF THE ORPHANS SIGNS is but one example of public art altering Albuquerque’s landscape. A nonprofit organization founded in 2009 by Ellen Babcock, assistant professor of sculpture at UNM, the group converts abandoned signs into unique art. Some of the earliest works involved rearranging letters on a reader board, like the regularly changing poetry brought to the abandoned Donut Mart sign on Lomas Boulevard, just east of University Boulevard. I’ve driven by when the sign reads A DAISY BETWEEB DUNES OR SIN MIEDO A NADIE (“with no fear of anyone”). Every time, I’m jarred out of my autopilot mode. Little details like these beg me to pay attention.

The orphan signs have gone up mostly on Lomas and along East Central Avenue, parts of the city that were hit hardest by the economic crisis of 2008, where many old businesses remain abandoned and empty even today. I met Babcock and Lindsey Fromm, an artist and arts educator who also works on the project, at Loyola’s Family Restaurant, a holdover from the Route 66 glory days, where endlessly refilled cups of coffee and big plates of biscuits swimming in gravy are the standard fare.

The pair often collaborate with students or community members on their projects, as with two of their newest signs, on Lomas just west of University. There, some students from the UNM Art Department took over two abandoned billboards visible to drivers heading east on Lomas. Both feature stylized photographs of industrial facades, with MIRA/LOOK on one and COME/GOES on the other. The lot the signs sit on used to be a car dealership, but it’s been empty for 10 years and looks like any other empty lot in any American city. But to me, these are the most Albuquerque of signs. “It was two bilingual college students from Albuquerque who designed these,” Babcock says, “and they say that they and their friends don’t just say ‘mira’ and they don’t just say ‘look.’ They always say both.” I imagine Burqueños driving by and seeing a part of their own identity there.

One of the most recent projects involved converting the sign in front of the old Sundowner Motel on Central, near San Pedro Boulevard. A nonprofit has remodeled it into mixed-income apartments, a quarter of which are set aside for people with special needs. Residents from the new apartments, as well as others from New Life Homes housing developments, helped with the design process. One side of the lit-up sign now features a photo of the Three Sisters volcanoes in Petroglyph National Monument, on the city’s west side, along with the text PASADO ES PASADO (“the past is past”). The other side features a close-cropped image of a lion’s eyes staring out in the direction of the Three Sisters.

“The residents wanted to talk about leaving the past behind,” says Babcock, “and they wanted an image of strength and resilience.”

“IT'S REALLY IMPORTANT TO ME THAT artwork that’s going to be in the community is somehow reflective of the community,” says Nani Chacon, an Albuquerque-based artist of Diné and Chicana descent who has created murals all over the world. In keeping with this philosophy, many of her murals in Albuquerque either feature influential community members or involve the community in their creation—including her best-known mural, at Washington Middle School, in the Barelas neighborhood, near Downtown.

The expansive mural, which stretches across one side of the school’s track, is clearly visible from the street. Against the wide field of cobalt blue stand two figures, a man and a woman, with flowering plants and monarch butterflies between them. Monarchs have become a common theme in much of Chacon’s work; they are symbols of migration and Resilience—the mural’s title.

Chacon created the mural with a team of students from Working Classroom, an arts and social justice organization in Albuquerque that provides educational programming and opportunities for student artists. Students attended workshops to learn painting techniques and make the final design with Chacon, then gathered plants from around Barelas that are usually considered “weeds”— like dandelions and silverleaf nightshade growing in sidewalk cracks—and painted them at a larger-than-life scale in the mural. Plants this size remind me that our urban ecosystem is a significant, though underappreciated, part of our non-human community. Maclovia Zamora, a curandera (healer) who influenced the mural’s theme, saw such plant life through a healer’s eyes as she crafted herbal remedies at the B. Ruppe drugstore, off Fourth Street and Barelas Road. Zamora once mixed teas and tinctures for a community that sought remedios outside the health care system. Chacon also painted a mural of Zamora on the pharmacy, which is now a community events space.

NUMBE WHAGEH ("OUR CENTER PLACE" in English) sits discreetly, almost overlooked, in front of the Albuquerque Museum in Old Town. It’s just a small swath of granite-covered ground, largely a conceptual piece, created by Nora Naranjo-Morse, an artist from Santa Clara Pueblo. A nearby plaque reads, in part:

Cycles begin, continue, and fade. It is out of this moist center place that the Towa, the Pueblo people emerged. From here, we, the Towa, know the clouds, mountains, winds, and all other creatures who swirl with us. This is our world place. Here we see beauty, feel love, and know a sacred wholeness … at Numbe Whageh, our center place.

This tender acknowledgment of land and heritage belies the controversy that spawned the artwork. Standing directly in front of and above Numbe Whageh is arguably the most controversial piece of public art in Albuquerque, La Jornada. This statue of Juan de Oñate and a crowd of colonists was commissioned by the city in 1998 for the 400th anniversary of Oñate’s arrival in New Mexico, an event that prompted Cuatro Centenario festivities all across the state and prompted a backlash from those who believed Oñate’s acts of genocide toward the Pueblo peoples weren’t worth celebrating or memorializing.

Originally, Naranjo-Morse was part of a three-artist team the city invited to collaboratively create the memorial statue. Of Spanish, Anglo, and Pueblo descent, the team was supposed to come up with a work that incorporated the many nuanced perspectives on Oñate. Instead, the artists disagreed so completely about the artwork that they weren’t speaking to one another by the end of the process, and Naranjo-Morse felt that she had to create Numbe Whageh in response.

These two works exist side by side in constant tension, showing the complexities of identities that also coexist in tension. To devalue one for the other would depict an artificial version of New Mexico, sanitized of violence and destruction, but also absent resilience. For public art to truly do its job—to speak to and for the community—it cannot exclude any voices. “It’s not ever there to make a statement,” Nani Chacon says. “It’s there to raise a question. And I think that question is then answered by the people who walk by it every day.”

Read more: Murals enliven the remote ranching village of Mosquero.

DRIVE-BY ART

Learn more about Albuquerque’s public art, here, which includes interactive maps and self-guided walking-tour brochures. The Los Muros de Burque website has details about how to hop onto the Albuquerque Mural Trolley Tour, a narrated expedition that explores more than 50 murals and public artworks around Downtown, Barelas, South Broadway, and Nob Hill. On the tour, you’ll learn about the background and meaning behind each artwork—such as the stylized mural of legendary labor-movement activist Dolores Huerta at the corner of Lead Avenue and Broadway Boulevard. Tours take place on the last Sunday of every month from May through October.