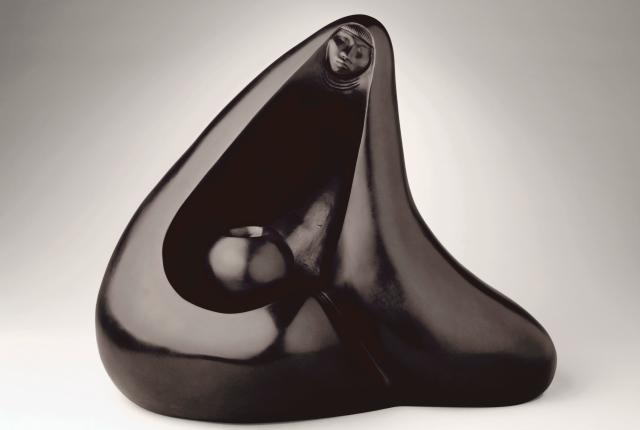

Above: Alan Houser's sculpture, Potter (1982).

Chiricahua Apache Allan Houser (1914–1994) believed that, in making art, he was “creating something you’ve never seen before.” As a master of multiple visual languages and media, Houser melded abstractions with references to Native people and forms from the natural world. The Silver City Museum hosts a mini-retrospective of his oeuvre through January 13. Allan Houser: Renowned 20th-Century Warm Springs Chiricahua Apache centers his history, culturally and artistically, within the longer timeline of southwestern New Mexico.

Born Allan Capron Haozous, he grew up far from those ancestral lands. His family, like other bands of Apache, was exiled from southwestern New Mexico and southeastern Arizona after Geronimo (Houser’s first cousin) surrendered to the U.S. Army in 1887. Many of Geronimo’s followers were eventually imprisoned at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Some stayed long after their sentences ended, including Houser’s family, while others incorporated into the Mescalero Apache tribe. Many years later, Houser reconnected with New Mexico when he became a student of Dorothy Dunn at the Santa Fe Indian School. He first picked up painting there in the 1930s, and, in time, began working in the round, eventually becoming the Institute of American Indian Arts’ first professor of sculpture.

While Houser’s work is very present in the northern part of the state, especially Santa Fe, Carmen Vendelin, director of the Silver City Museum, wanted to bring it south. “There’s a vacuum as far as trying to talk about contemporary Apaches who have roots here,” she says. With 27 works, including sketchbooks and maquettes for larger sculptures, the exhibition begins to fill that vacuum. It brings Houser’s voice back to the place where his people made their home at a significant moment in time: The Chiricahua are now attempting to repatriate to New Mexico.