IN ENCOUNTERING ROCK ART, the initial impact is the image itself. How do we understand the meaning behind the diverse life forms and abstract designs painted and carved throughout the arid landscapes of the American West? Are they to be taken literally or might they stand for something else?

It is commonly the case that outside observers will impose their own views on what is seen. If there is any possibility of approaching rock art’s various meanings, we have to learn its symbolic language, which is inevitably cast in terms of what are to us unfamiliar relationships between things.

Among the cosmological principles given visual form in rock art of the American Southwest, for example, are motifs that unsuspectingly represent dual complementary forces. These motifs include representations of deities that embody these factors. Among them are the Hero Twins, or War Twins, of the Navajos, who assume male/female gender roles as they cooperate in creating a safe world for the Navajo people.

Man in an animal pose, Mimbres, around 1000–1130 CE, New Mexico. The combined human and animal characteristics erase the distinctions between them. Similar examples can be found on classic Mimbres black-on-white ceramics.

Another example is the horned and oft-feathered serpent, who is represented in Mimbres, Jornada Mogollon, Casas Grandes, and Pueblo rock art and continues to play a role in Pueblo art and ritual today. Exceeding the boundaries of the natural world, this serpent is a notable case in point, as it represents both celestial and terrestrial realms, amplifying its reach.

In Ancestral Pueblo art and in Mexico, as an aspect of Quetzalcoatl, the serpent assumes the war power of Venus as Morning Star, which in late Ancestral Pueblo art is conflated with predatory birds and portrayed as a scalper. On the other hand, as a terrestrial entity, the feathered and horned serpent provides water that facilitates the growth of corn. In a broad sense, the uncertainties of existence are embodied in the complex symbolism of this serpent god, which represents the earth and sky, corn, and life itself, as well as the fearsome power of political authority.

When it comes to interpretation, there are many cautionary notes. Are representational figures simply what they appear to be? Are snakes lacking distinguishing features simply snakes? Is a deer simply a deer? Is a duck just a duck? A sheep a sheep? Are they good to eat? (It is a common—and simplistic—supposition that the ancients made pictures of their food just for the sake of it, so to speak.) If ducks were food, why are they often sitting on people’s heads?

A single icon can be used as a starting point.

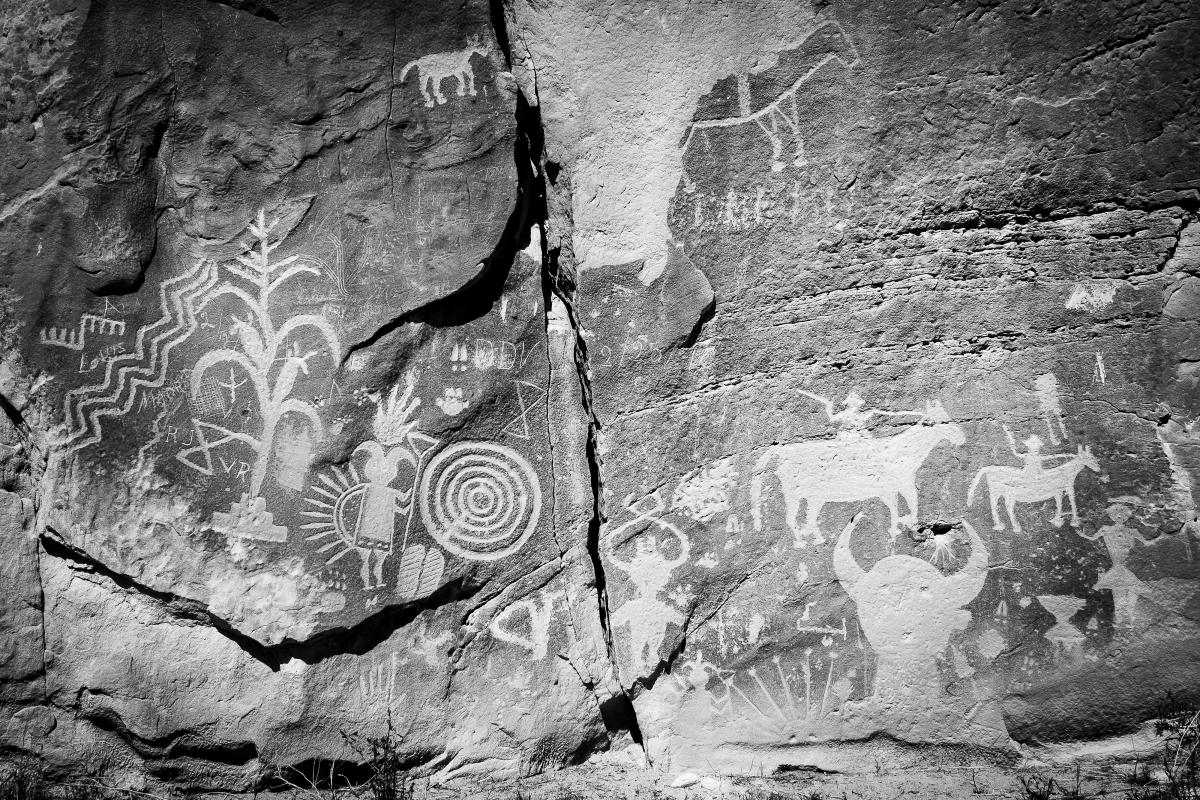

Jornada Mogollon–style petroglyphs on scattered boulders along a rocky ridge in southern New Mexico.

THE SPIRAL

Imagine a person, most likely a Pueblo man from a nearby village on the mesa top, approaching a cliff above a trail. He pauses before the blank wall of stone and scatters an offering of cornmeal.

This is not an unusual gesture. It is simply expected Pueblo protocol, a courtesy based in an underlying assumption that you need permission to impose something onto this cliff face, which like everything else is part of the ambient animistic universe. Not to ask would be offensive and possibly even dangerous. So he asks.

His intent is to carve an image into the cliff, and with the necessary tools at his disposal—stones and perhaps a piece of antler—he carefully pecks out a spiral. Why here? Is it a marker? Does it function like a street sign to designate the approach to the place along the cliff, where the trail forks and ascends to the village? But since everyone knows where that is, does the spiral have another function?

A Pueblo spiral found in New Mexico.

Some spirals, via interactions with sunlight and shadows playing across the rock face, appear to mark solstices and equinoxes and thus seasonal changes important to farming communities that tie their ritual events to seasonal cycles. Is this happening here? Is the man a sun priest? If not, what else might explain the appropriateness of a spiral on this cliff? Hundreds of years later, there are no secure answers as to what the spiral signified.

The spiral, a simple and familiar figure found in the rock art of many cultural origins, is particularly common among the stone canvases of the Hohokam and the Ancestral Pueblos of the American Southwest. As a frequent element on sandstone walls, boulders, and igneous outcrops, it poses a challenge, forcing the observer to engage with it to grasp what the artist intended in each case.

Contemporary commentary from Pueblo people indicates that there is no single interpretation but that the spiral has multiple potential meanings. Movement is inherent in this design, and water, wind, or a journey—a spiraling inward to the Center Place—are all implicit in the spiral motif. Further, according to the Zunis, the journey to the center is also a search for knowledge. In addition, the Center Place is an active concept in the here and now, actualized by the central plazas in contemporary Pueblo villages.

Paired horned serpent deities in New Mexico. The large cross shape at the tail of the left-hand serpent may indicate a rattlesnake, a cloud, or, equally likely, Venus, the Morning Star, with which the deity is often associated. The figure also has a collar, symbolizing corn that he delivers in ritual events.

Thus the idea of the center is simultaneously both abstract and specific. Here also, boundaries between the physical and spiritual realms are permeable and blurred. For a given Pueblo village, the center is a specific location symbolized in the village plaza. It is both fixed and flexible, however, so if the village moves, so does the Center Place. Does a double spiral on a rock or elsewhere denote migration from one place to another? Perhaps, but there are other possible meanings, one of which is inherent in the northern Tewas’ description of movement of blessings from the earth.

For the Tewa of Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo in the northern Río Grande Valley of New Mexico, the cosmological diagram of the Tewa world takes the form of a set of nested squares around the south plaza, which is the true center of the village. In distanced progression outward from this center, shrines, hills or mesas, and mountains of the four directions are designated. They define the Tewa world, through which blessings are said to travel.

The village center is called the “Earth mother earth navel middle place,” to which the mountain earth navels on the periphery of the Tewa world send the blessings they have gathered “from all around,” which are then directed inward toward the village. These geometric patterns on stone are more than designs; they are expressions of complex belief systems.

Warrior deities supplement the protective agencies of Morning Stars and shield bearers. Portrayed in this New Mexico petroglyph is a widely known warrior woman, distinguished by her divided mask.

Why spirals were so commonly pecked on rocks remains an unanswered question, although there is reasonable evidence in many cases that some of them served as ritualistic solar markers to designate solstices and equinoxes, important dates in the agricultural/ritual cycles common to farming cultures.

Cliffs and boulders correctly situated would have provided numerous opportunities for carving spirals that documented the sun’s movement by means of interactions with sunlight and shadows and would have functioned as significant components of the cultural landscape. These considerations involve the meaning/place/time tangle mentioned earlier.

Although a spiral may evoke multiple meanings, depending on the viewer, there is power in ambiguity, thus accounting for the spiral’s popularity, however contradictory this might seem.

A bold design with stepped clouds was adapted to this tall rock face in southern New Mexico.

STEPPED CLOUDS

The visual vocabulary of rain cosmology looms large in the rock art of southwestern agriculturalists, beginning around 1000 CE or slightly earlier. This graphic “lexicon” is diverse and complicated, as it portrays rain deities and other spirits, pottery vessels, cotton textiles, and rain clouds all in an interrelated system. This packet of complex associations entails relationships between things foreign to Western thought.

The frequently encountered and familiar triangular stepped cloud motif pervades Jornada Mogollon and Pueblo graphic media, including rock art, textiles, and ceramics. Fundamental to the graphic expression pertaining to rain cosmology, and in many ways uniting it, the stepped cloud may take the form of a full-fledged stepped pyramid or it may be just a half pyramid, with “steps” on only the long edge. Such edges are often juxtaposed to create a jagged space that can be interpreted as lightning, thus making it more inclusive.

Pyramidal stepped clouds may be elaborated with falling rain or a rainbow in the base. Such depictions translate into visual metaphors of a water mountain. The widespread concept is related to rain cosmology in Mesoamerica and its peripheries, where mountains are envisioned as great storehouses of water, as testified by mountain lakes, caves, and springs. It is said that mists from these terrestrial sources rise to form rain clouds. Thus, the water mountain, depicted as a stepped triangle, is associated with bringing rain to the arid environments of the American Southwest.

Pyramidal stepped clouds may be elaborated with falling rain or a rainbow in the base.

Just as the stepped cloud motif has rain-making connotations, so do bowl-shaped kachina masks frequently found in rock art. Today among the Pueblos, ceramic vessels such as water containers assume ritual roles as symbolic springs. In rock art of both the Jornada Mogollon and Pueblo world, the faces of some rain-bringing kachinas are in the shape of bowls or jars, thus compounding their message. Some of these are decorated with stepped clouds.

Many of the textile patterns on the rocks in these regions are large, detailed, and meticulously crafted, involving skill and time consumption, factors that indicate their importance. Why are these designs commonly found on textiles and ceramics laboriously carved on cliffs and boulders under the open sky? To speculate, were textile patterns associated with social groups and therefore pictured on rocks to promote status, wealth, and authority? Were they identity markers? Did they have a role like a billboard in a textile trade? So far there is little evidence to support such interpretations. More consistent with Pueblo cultural practices is the suggestion that the rocks so decorated were “clothed” with textiles—that is, they were thought of as “stones wrapped with clouds.”

Birds were a popular subject in the Río Grande Pueblo world and, along with other life forms, were chosen for representation for their symbolic cosmological associations.

HUMAN FORM

People portrayed as hunters, warriors, and ceremonialists, or in scenes related to fertility and birth, suggest persons engaged in the activities of everyday life. Thus, they convey messages pertaining to social and gender roles, social hierarchy, or participation in religious rites. But they are rarely alone. Instead, various kinds of interactions and relationships are drawn between anthropomorphs and birds, animals, insects, and even plants. Overall, human figures send mixed messages when they are distorted or even conflated with other life forms and exceed the natural realm.

In the greater Southwest and beyond there are humanlike figures whose identity as humans or spiritual entities is ambiguous. Painted by hunter-gatherers several thousand years in the past, these elongated human silhouettes, hovering against expansive sandstone backdrops, are among the most emotionally evocative figures lurking in the canyons on the northern Colorado Plateau.

A high point on a basalt dike in northern New Mexico is a focus of these pecked hands of Pueblo origin.

There is something fearsome, something confrontational in figures that look human but are not. It is not at all clear what these immobile, large, and looming figures represent. Typically they lack appendages, but at times an arm is added, rather awkwardly, to support a small creature. In one painting, a rabbit runs down an arm. Other than their oversized staring eyes, they lack other facial details, while their simple tapering torsos may be filled with fine patterns that include snakes and other animals. The small birds and insects that fly around them are viewed as “messengers” or spirit helpers, conveying information and knowledge from or toward the immobile human shapes, which may represent shamans in trance or otherworldly powers encountered on spiritual journeys.

Via a large number of rock art styles of diverse cultural origins, over millennia, the details of costuming and associated ritual paraphernalia—including feathers, antlers, horns, entire animal heads, and other references, such as pictured syntheses of disparate life forms—convey the perception of a conceptual continuity between all species, each with its own specialties, suggesting a sense of universal dependency on shared knowledge. These representations allude to the idea that supernatural powers that humans lack are inherent in other species. In turn, this suggests a hierarchy of beings and knowledge within which humans are actually dependent on the powers controlled by other forms of life, resulting in a complex world order that differs from and challenges our worldview today.

An isolated boulder in southern New Mexico includes hands.

Far from being inert renderings from an ancient past, rock art, regardless of age, has an impact on any viewer, demands comprehension, and provokes responses. William Frej’s photographs are one response to rock art. The photographic work represents an effort to see these paintings and petroglyphs as they are today in their landscape contexts. The artists have long vanished, but their insights and ideas “written in stone” remain. They continue to speak from the past, bringing to us in pictorial form a diversity of ideas, cosmologies, and beliefs of the first Americans.

Read more: Near Las Cruces, a hike to ancient petroglyphs brings whispers of the past.

William Frej is an award-winning photographer who has spent decades studying and photographing the petroglyphs of the Southwest and Indigenous architecture and cultures around the world. Archaeologist and artist Polly Schaafsma is an authority on the pre-Hispanic Indigenous rock art and kiva murals of the greater American Southwest.

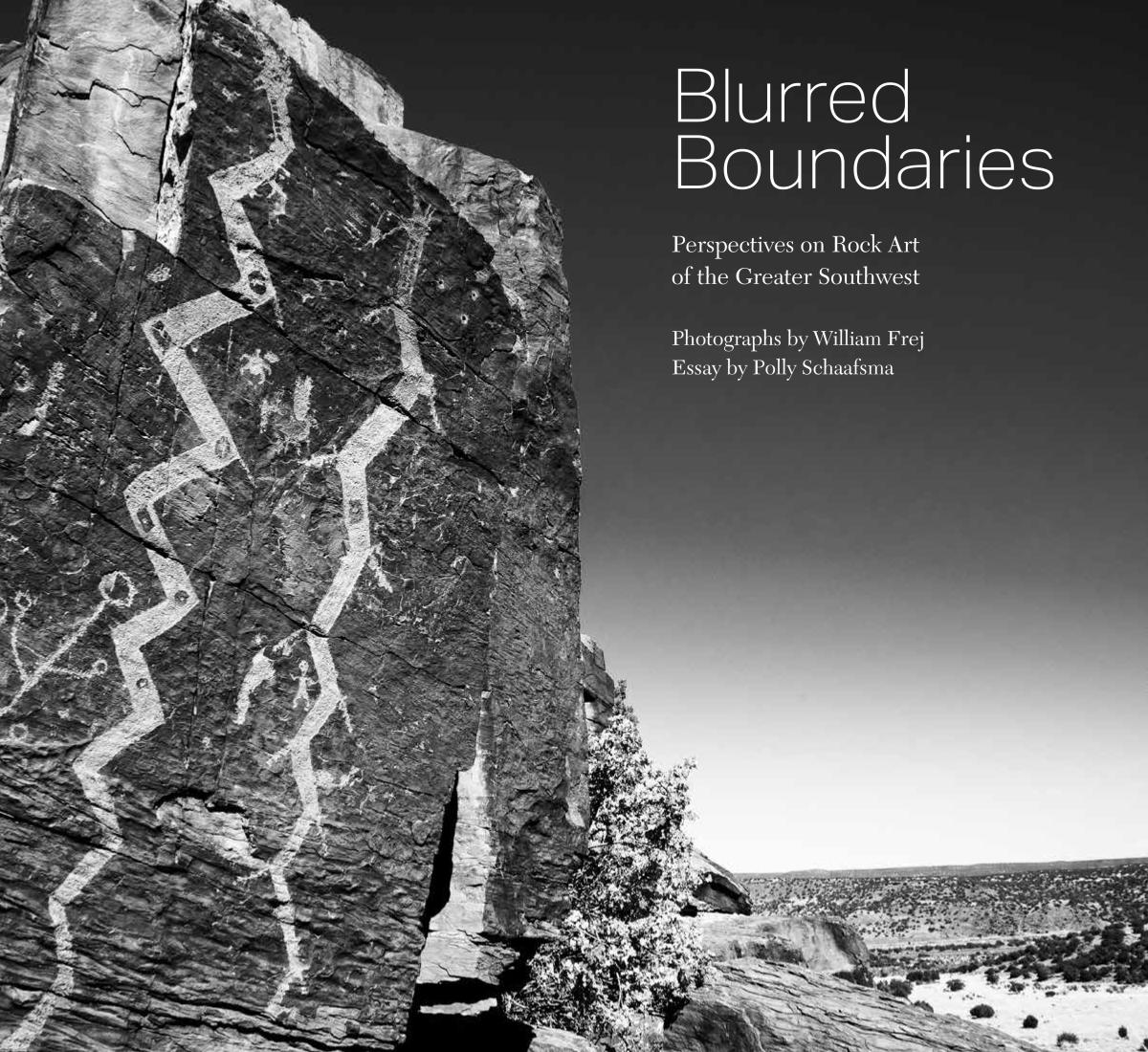

Published in 2023, Blurred Boundaries: Perspectives on Rock Art of the Greater Southwest (Museum of New Mexico Press) is a lavishly illustrated tome that uses William Frej’s black-and-white photographs to illuminate the mysteries of the region’s imagery. Find a copy at bookstores or online.