DIRTY WITH AGE AND SMALL ENOUGH to fit into the palm of a hand, the cased photograph held just three clues. Its technology—an ambrotype, essentially a glass negative placed on a dark background that turns the image to a positive—dated it to between 1850 and 1865. The group of men wore uniforms, a hint that they could be soldiers. Corbels and vigas topped the wall behind them, signifying that they were probably in the Southwest, and maybe New Mexico itself.

The New Mexico History Museum’s Palace of the Governors Photo Archives needed Civil War–era images for an exhibit. Could its staff have stumbled upon a winner in a stash of nearly one million photos, many of them orphaned and undocumented?

They needed to do some detective work to make sure.

First, a conservator treated its backing. Then archivist Hannah Abelbeck pulled a digital scan so detailed that, once the image was enlarged, the letters “FFC” could be read on one of the hats. She posted it to the archives’ Facebook page and asked its avid followers for help. One spotted what looked like a speaking bugle, a common tool among firefighters of a certain era. “FFC,” said another, could mean “Santa Fe Fire Company.”

A group of five men from the Santa Fe Fire Company, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1861-1880. Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA) 145773.

“That gave me enough keywords that I could look for related documents,” Abelbeck says. “I found that the Santa Fe Fire Company was incorporated in 1861 and got the names of people who signed the incorporation docs—which they may be holding in the picture. Then I tracked down images of those people and started matching them up.”

It indirectly filled the Civil War hole, as at least two of those pictured were known to be New Mexico volunteers, but it also added color to a fragment of New Mexico history, a task that falls, in part, to such guardians of our visual past. For researchers, authors, genealogists, people who love exploring history, and even those who want affordable art for their walls, these repositories exist throughout the state in museums, universities, historical societies, and libraries. Some hold a few shoeboxes of snapshots. Others burst at the seams.

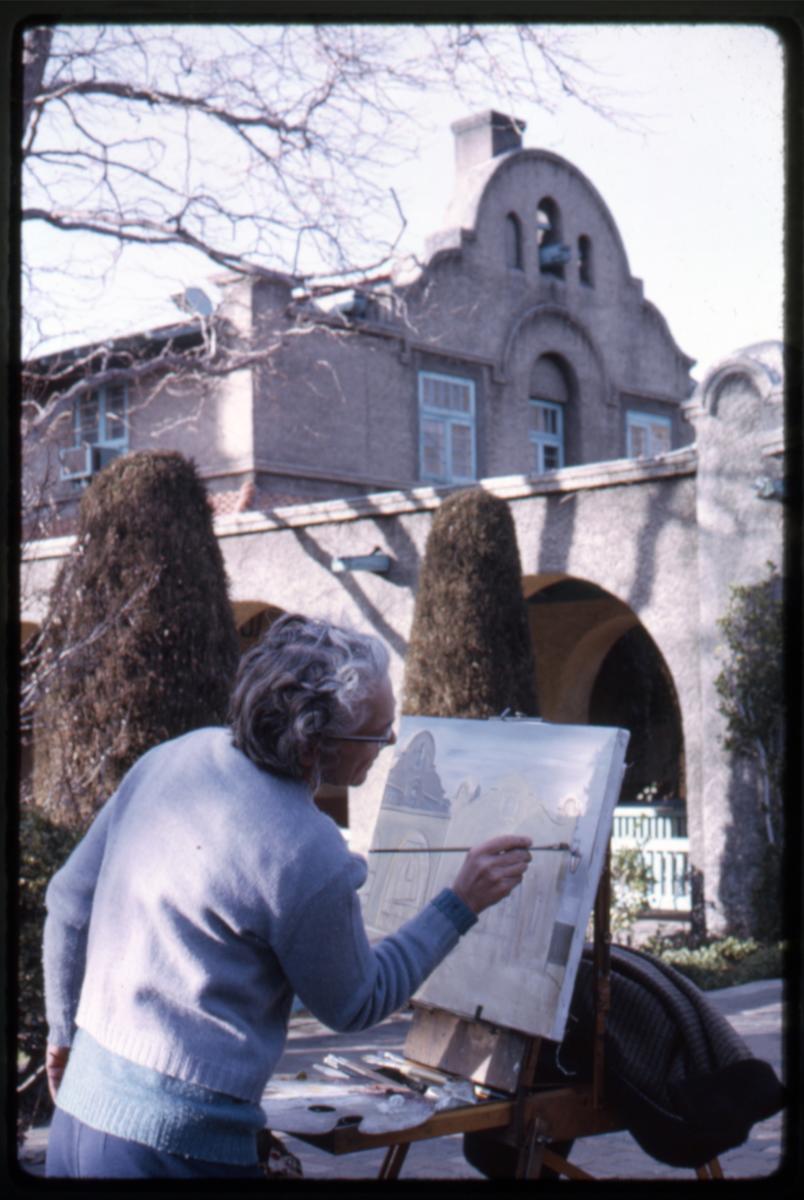

A painter at Albuquerque’s Alvarado Hotel, 1969. Photograph by Walter McDonald, Albuquerque Museum, PA1996.006.136.

Three in particular stand as exemplars—the Palace Photo Archives, the University of New Mexico’s Center for Southwest Research, and the Albuquerque Museum. During COVID-19, most research has been limited to email, although UNM’s center has occasionally been able to offer by-appointment hours. All strive to digitize as many photos as possible, meaning that anyone with a computer can “visit” anytime.

“Handling real things, though, that’s the fun part,” says Cindy Abel Morris, the Center for Southwest Research’s pictorial archivist.

Jillian Hartke, digital archivist for the Albuquerque Museum, agrees. “I get all caught up in stories. I learn so many things and fall down so many rabbit holes. This job is a blast.”

Pilot Katherine Stinson, ca. 1910–19. Center for Southwest Research, Katherine Stinson Collection, 000-506-0053.

KATHERINE STINSON FOUND A MEASURE OF early-19th-century fame as one of the nation’s first female aviators. But she wasn’t just a pilot. She and her mother created a company to design and build aircraft. With her siblings, she started a flying school. She couldn’t serve in World War I but trained some 100 pilots who could. Then she founded the Society of Women Engineers.

Eventually, a bout with tuberculosis forced her to move to New Mexico. She found the cure at a Santa Fe sanatorium and met her future husband, Miguel Otero Jr., son of a former territorial governor. She shifted to architecture and designed homes, including one for Dorothy McKibbin, the gatekeeper of the Manhattan Project.

The Center for Southwest Research holds a few photos of Stinson. “She’s someone that we should know more about and that more people should know of,” Abel Morris says. “Something that many cultural and historical collections are dealing with is that a lot of the photos are of men. I’m always interested in collections by or about women.”

A man views Truchas Peak from the Pecos Mountains, New Mexico, 1940. New Mexico Tourism Bureau, New Mexico Magazine Collection, Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA) HP.2007.20.486.

The center has amassed more than 500,000 photographs. (They pour in, mostly from personal collections, faster than archivists can keep track.) Beyond the physical holdings, it oversees an online search portal hosting 155,968 digitized images (not counting historical documents, postcards, and maps) from 43 New Mexico organizations, including the Farmington Museum, New Mexico State University Library, Roswell Museum & Art Center, and Corrales Historical Society. Altogether, the center’s New Mexico Digital Collections website takes a mere bite of all the organizations’ photos—but it’s still enough to keep a history hound searching for days.

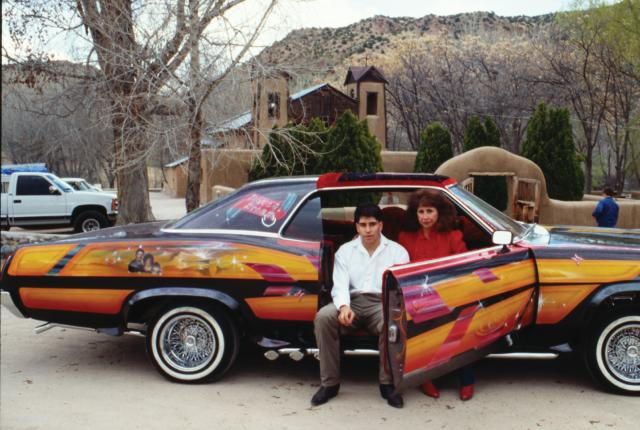

You can find images of miners from Ratón to Silver City, railroad workers, Harvey Girls, the Mexican Revolution, restaurants, fiestas and feast days, lowriders and landscapes.

The Albuquerque Museum posted about 200 images to the site before investing in a stand-alone e-museum, which now tallies around 6,500 images. The bulk of the collective website’s images come from the Palace’s collections.

They are a sight to behold.

Housed in the lower level of the New Mexico History Museum’s Fray Angélico Chávez History Library, the photographs fill a warren of rooms containing shelves of boxes, rows of file cabinets, and a few freezers to preserve silver nitrate and acetate negatives. The collection began in the 1880s, when the Historical Society of New Mexico somehow intuited the future importance of the young medium and built relationships with people like famed explorer, artist, and photographer William Henry Jackson.

There are daguerreotypes, tintypes, lantern slides, a solid chunk of photos from both New Mexico Magazine and The Santa Fe New Mexican, and, increasingly, born-digital pics. Despite the seeming glut, all three archives share a concern about the holes within their collections. For generations, photography required money, and the people who could afford it brought their biases to bear on their subjects.

An Isleta Pueblo woman sells fruit to a soldier on a passenger train, 1912. Albuquerque Museum, gift of H. Leonene Smith, PA1994.010.010.

Native people were posed in ways to uphold the “stoic Indian” stereotype, often in costumes and settings invented by the photographer. Their names, along with those of Hispanic villagers, usually went unrecorded. Other minorities were ignored altogether.

“We have only one photograph of a Chinese man, a portrait in 1890,” says Hartke. “We don’t know who he is. We can always use more women’s history. Suffrage was a big research topic in the last few years, and I feel we were abysmal in providing images. We have 1914 footage of a parade, but only about 15 seconds of it.”

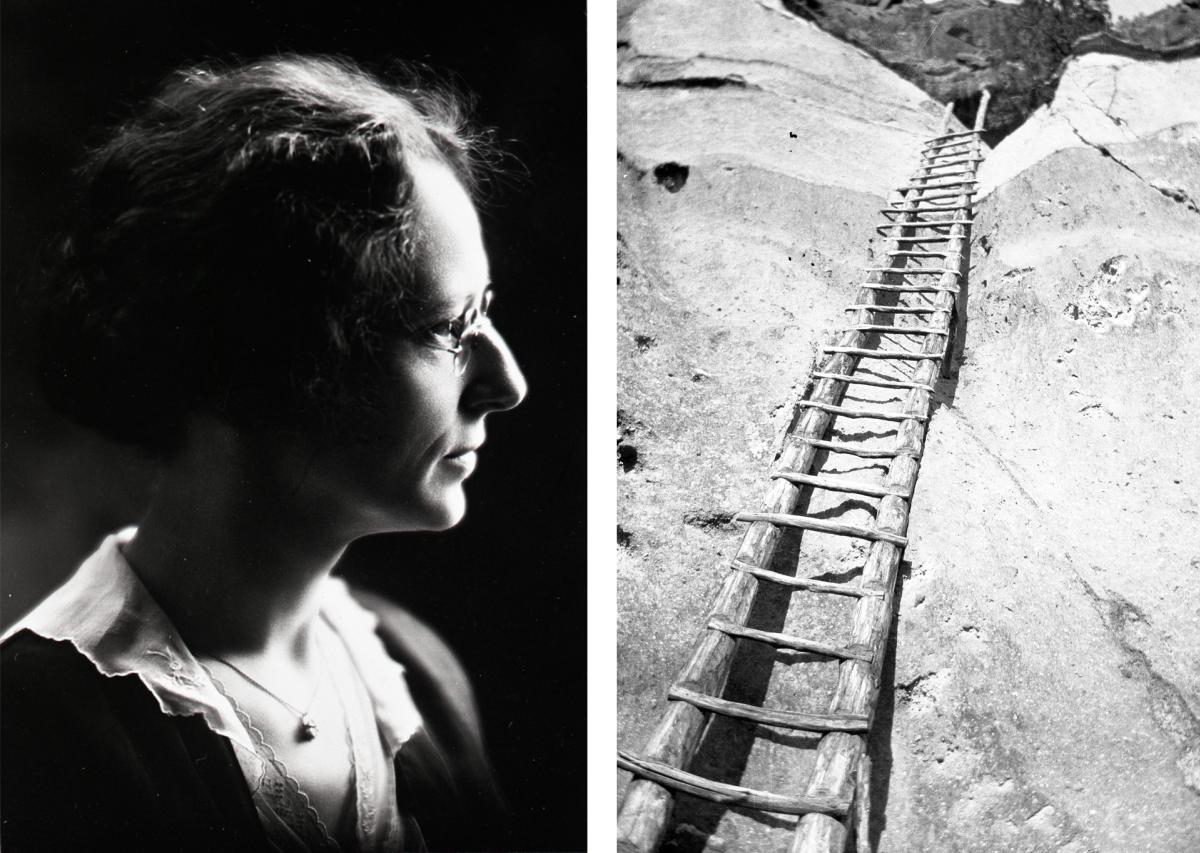

On the plus side, Albuquerque once boasted a handful of large portrait studios run by women—Alabama Milner, Eddie Cobb, Emma Albright—and the museum holds much of their work. “They made it through the Depression and World War II,” Hartke says. “It’s this incredible story of the gumption they had. They weren’t just successful—these were the longest-running studios in the city.”

Alabama Milner’s portrait, ca. 1930, Albuquerque Museum, gift of Margaret R. Herter, PA1994.015.012. An Alabama Milner photo of the ladder at a cliff dwelling, ca. 1919–50. Center for Southwest Research, Herter/Moon Collection, 2015-008(3)-0089.

PRIZEWINNING STATE FAIR ANIMALS ABOUND in the Albuquerque Museum’s digitized photos. There are also 1962 cancan dancers at the Red Bull Saloon, in the former Little Beaver Town theme park. The 1971 riots on the UNM campus butt up against images of the whimsical lodgings that once dotted Route 66—the Mars Motel, El Jardin, and the Urban Motor Lodge (“recommended by Duncan Hines”).

Rafts of photos feature the fronts of houses, a treasure trove for people who live in those dwellings today. And a 1969 series on the mundane activities of downtown Albuquerque—pedestrians, businesses, traffic—turn into a collage of fashion, car models, signage, and the stores that once drew daily shoppers.

People still take those photos, but today they rarely bother to print them out and write down what they depict or who was in them. That worries archivists. What will future historians use to illustrate our present, once it has passed?

“You’re not going to find a box of photos in the attic from 2010,” Hartke says.

A circa 1920 Milner Studio shot of an Albuquerque service station. Albuquerque Museum, gift of Bob Davis, PA1992.005.812.

At its heart, Abelbeck says, “photography captures the refraction of light off a scene that once was. The images become minable for research, but it depends on how well they’re labeled. Once that information is detached, piecing it back together is really hard.”

Given that, archivists actively plot how to store digital photos in formats that last longer than the floppy disk era did, even as the pace of photography accelerates. “I was really hoping this year I would be able, for my annual performance goals, to say, ‘I’ve done five collections,’ ” Abel Morris says. “But I’ve only done two, because we can’t work on-site as much.”

Read More: The 20th Annual New Mexico Magazine Photos of the Year

Hanging in the balance are the stories of places that may not last, of people who will pass on, and of events that can affirm our humanity. The Albuquerque Museum holds a small collection of photos from the Dawson coal mine, near Cimarrón, which earned infamy for a pair of disastrous explosions before closing and leaving little more than a haunting cemetery behind. The photos were taken in 1910, before the accidents, and show the town doctor running workers through safety drills.

“It’s incredible to look at these images and know that some of those people actually had to respond to a disaster a couple of years later,” Hartke says. “There’s something really valuable about telling stories this way. When you see a face from the past, it’s powerful.”

PHOTOGRAPHIC MEMORIES

Visit the Center for Southwest Research, when open; by appointment.

Watch the Albuquerque Museum’s YouTube series Picture This to hear backstories of photos in the collection.

Follow the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives on Facebook and Instagram for a daily assortment of historic images.

GO DIGITAL

Surf New Mexico Digital Collections online and Albuquerque Museum collections on their website.

Lead photo: Dave Jaramillo's son, Dave Jr., and wife, Irene, with his lowrider car, El Santuario de Chimayo, New Mexico, 1992. Photograph by Annie Sahlin, Dave's Dream series. Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA) HP.2013.12.31.