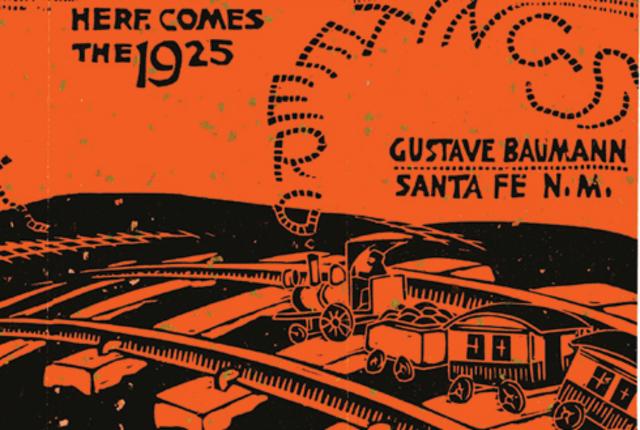

Holiday card by artist Gustave Baumann.

IN THE WINTER of 1919, Gustave Baumann sat down with a small wooden block and began to carve. He worked briskly, probably in a rented studio on Santa Fe’s Canyon Road, where he’d settled thanks to a loan arranged by the curator of the Museum of Fine Arts. What he was about to make wouldn’t earn any of that money back.

A few lines became a bucking bronco. As a Chicagoan new to the Southwest, Baumann couldn’t have had much experience with his subject, yet the horse’s rider took on a natural lean, flinging his hat out to keep his balance. Quick squiggles evoked dirt. When he’d finished carving, Baumann coated the woodcut in green ink and pressed it to paper, printing the inverse of what he’d etched. A second block, carefully aligned on the same sheet, set bronc and cowboy against a deep blue sky. Underneath he printed a hand-carved pun: HAPPY OR BUST.

It was the first Christmas card Baumann made in New Mexico, and it set the tone for the many that would follow—one almost every year for the next 50 years. Unlike the elegant fine art prints he was famous for, it was funny and loose, intended for his friends. It favored local symbols over seasonal clichés. And it was cheerful, not in the obligatory Merry Christmas sort of way, but as Baumann naturally was. On the back of the card he added the whimsical logo of his Koshare Press. Borrowing a phrase from Adolph Bandelier, he referred to the Puebloan sacred clown as a “delight-maker.”

“OH MY GOSH,” the antiquarian bookseller Jean Moss thought when she stumbled on the Christmas cards while appraising Baumann’s archive. “This would just be a wonderful exhibition.”

In addition to Baumann’s fifty or so handmade cards, she found hundreds he’d received over the years from his wide circle of friends. Among them were some of New Mexico’s most beloved artists and intellectuals, men and women who’d helped cement the reputations of Santa Fe and Taos as creative havens. Ernest Blumenschein and B.J.O. Nordfeldt were represented. So were the pioneering serigrapher Louie Ewing, the Taos printmaker Barbara Latham, and Willard Clark, whose mechanical press Baumann sometimes borrowed for his own cards when he was in a rush.

Moss, a frequent dealer in artists’ ephemera, recognized the trove’s appeal. Homemade Christmas cards were an idiosyncratic document of their makers’ lives, a blend of art and correspondence, offering an insight that their paintings don’t.

“They had a sense of community,” Moss says of the artists, “and they all had a sense of humor.”

Excited, she approached Tom Leech, director of the Palace Press, about working together to bring the collection to the public.

“My first reaction when I saw the cards?” Leech recalls. “Just delight.”

The exhibit that Moss and Leech curated, Gustave Baumann and Friends: Artist Cards from Holidays Past, is on display at the New Mexico History Museum through March 29, 2015. It includes about 100 of the cards in Baumann’s collection, arranged according to seasonal themes such as “Angels and Madonnas,” as well as topical ones like “War and Peace.” An accompanying book from the Museum of New Mexico Press contains a slightly smaller selection focused on New Mexico artists.

Particularly in the latter context, Baumann appears as the hub of a lively social set whose common bond was creativity. “Many of Baumann’s circle were refugees from the commercial world,” Leech says, “in that they all made this conscious decision not to be commercial artists, but to come out here and be fine artists and pursue their vision.”

That vision reveals itself in all kinds of ways in the cards. Will Shuster’s 1945 lithograph depicts a miniature Zozobra— the Santa Fe icon that he and Baumann invented together—leaning beside a Christmas candle. John Gaw Meem contributes a nativity bulto printed on architectural paper using the blue-line process. Baumann’s own woodcuts are wonderfully unpredictable, from designs based on regional petroglyphs to reproductions of his daughter Ann’s scribbles on gold-flecked pink-and-orange Chinese paper.

New Mexican motifs—adobe buildings, burros, Pueblo dancers—pop up often. “These artists were quite—if you can accept the cliché—enchanted with New Mexico. They really wanted to be here, and were fascinated by it,” Leech says. Global concerns also figure prominently. Viewers can track the progress of the Depression and World War II through the cards, in which unhappy history often receives a wry twist. One Prohibition-era Baumann print depicts a bouncing barrel that, the book notes, may be “full of something other than ginger ale.”

It wouldn’t be hard to believe. “I think Christmas was a season of big parties for all the artists,” Moss says.

Baumann liked to perform marionette shows in his living room on Christmas Eve. Afterwards, a group of friends would drive to the pueblos to see Christmas dances. It was on one of these outings that Baumann met his wife, Jane, at San Felipe Pueblo in 1923. His card that year features colorful ristras and the inscription GREETINGS FROM THE LAND OF MANANA, BURROS & CHILI.

Last year, Americans bought over one and a half billion Christmas cards, most of them produced in commercial print shops like the one where Leech once apprenticed, an unmagical factory full of screeching presses and foul chemicals. Committee approved cards are printed 32 to a sheet, 5,000 sheets an hour. “They might as well be Pop-Tart labels,” Leech says.

As for Baumann, he kept crafting eccentric holiday greetings by hand right up to his last Christmas, in 1970. Though age and arthritis simplified his carving, out of his half-century in Santa Fe, there was only one year, in the late sixties, that illness kept him from making a card. To keep the homemade tradition alive, Jane Baumann mailed friends two snapshots of the gray-haired couple sharing in some joke.

“Merry Christmas,” she wrote on one. “Happy New Year,” said the other. And on the back: “We think it’s best to exit laughing.”