Virgil Ortiz at his Cochiti Pueblo home. Photo by Minesh Bacrania.

Virgil Ortiz at his Cochiti Pueblo home. Photo by Minesh Bacrania.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

Spoiler alert: Virgil Ortiz just might have superpowers. Mild-mannered by day, the Cochiti ceramist mounts exhibitions of his work in museums and galleries at an inhuman clip, while somehow finding time for adventures in painting, photography, video, digital art, screenwriting, and more. He’s an imaginative time traveler, passing freely from traditional clay figures inspired by Pueblo history to futuristic sci-fi dreamscapes. And should he ever need a cape, he can supply one himself, thanks to his personal fashion line, born of a collaboration with Donna Karan.

With so much going on, his reaction to receiving a Governor’s Award might as well be a tagline for his life so far. “The reality,” he says gently, “hasn’t really hit.”

True to comic-book convention, Ortiz’s backstory begins simply. He was raised in Cochiti village by a potter mother and a father who makes drums. “We were all creating art growing up. It was just part of everyday life,” he says. His mom, Seferina Ortiz, was well known for her work. She taught Virgil to craft ceramics as her own mother, Laurencita Herrera, and countless generations before them had, gathering clay and mixing paints themselves. He still produces much of his work this way, putting in weeks of labor for a single 20-inch figure.

As a child he accompanied his parents to Indian Market, where they manned booths while he and his friends roamed Santa Fe on foot. In the summer of 1977, when he was eight years old, the kids wandered over to the movie theater at the DeVargas Center and bought tickets to Star Wars. After the credits rolled, they watched it again. And again. “We probably saw it ten times that weekend,” he laughs. It was his first brush with science fiction, and started him dreaming of worlds far, far away from northern New Mexico. By their teens, he and his friends were escaping to New York, Chicago, and L.A., soaking up culture and lusting after clothes they couldn’t afford. When they came home, they taught themselves to sew and made their own forward-thinking fashion.

But it was ceramics that first earned Ortiz a reputation as an artist. While his mother’s generation made popular storyteller figurines, the teenage Virgil experimented with standing clay figures that recalled an earlier tradition. An Albuquerque collector took notice and invited him to see his trove of 19th-century Cochiti art. “A lot of the things they made back in the day were taken from circus sideshows that came through on the railroad, so the cooler pieces were all Siamese twins and tattooed bodies and just really grotesque, outside-the-box stuff,” he says. The weirder his own work got, the more people took notice. He was hailed as an innovator, “but it was just reviving pieces based in social commentary.”

Today his figures tell a story he’s been dreaming up for years, one that jumps back and forth between the history of the Pueblo Revolt and a parallel struggle set 500 years later, in 2180. The futuristic bits pit Puebloan heroes called Aeronauts against extraterrestrial conquistadors in a Southwestern space opera that would make George Lucas proud. Ortiz is shopping a screenplay around Hollywood, bundled with elaborate character and costume designs that marry his many talents to those of collaborators like the Santa Clara artist Rose Simpson. The goal is to raise awareness of Pueblo history, which he sees as a saga of perseverance that’s been neglected lately. “Everybody’s on iPads, they’re on their phones,” he says. “You’re only going to compete for their attention if you have something as cool as what’s out there.”

Ortiz gets attention like Batman gets bad guys. When he’s not manning his own pop-up gallery and gift shop at La Fonda during Indian Market, he’s putting in appearances at the Denver Art Museum, where a current one-man exhibition tells his Pueblo Revolt story in various media, or the Albuquerque Museum, where his massive installation (a life-size warrior figure and her fantastical shoes on a high platform) welcomes visitors to the Brooklyn Museum’s touring show Killer Heels. But like any hero, all he really wants to do after each new conquest is head home, back to his Cochiti studio.

“After all the crazy advances that human life is experiencing right now—yes, it’s really futuristic and awesome, but it’s going to come back to a simple way of life,” he says. “That’s what my prediction is. When all else fails, it’ll come back to the basics.”

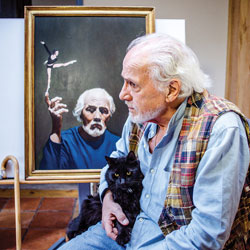

Vincent Figliola in Las Cruces with

Vincent Figliola in Las Cruces with

Self Portrait with Ballerina.

Photo by Robert Stebler.

KEEPING IT REAL

“I don’t do superreal,” Vincent Figliola insists. Turns out reality is something of a balancing act. When he moved to Las Cruces in midlife to become a professional painter, it took Figliola years of frustration to master his technique. By the time he got it down, he’d overcorrected to the point that people would mistake his paintings for the photos he’d based them on. He learned to compromise by working from multiple images, picking and choosing the bits that suited his purpose.

“What I’m really looking for is expression,” Figliola says. “I’d like people to feel what that person might be going through or might be thinking. And I’d like it to be not a handsome cowboy riding a horse. I’d like it to be a broken-down cowboy, if it’s going to be one. I want humanity.”

Take his “Crossing” paintings, for example. Back when their house abutted 75 miles of border desert, Figliola and his wife, Barbara, used to hear Spanish outside their window at night. At first he called the police, who seemed reluctant to get involved. He soon realized why: The voices belonged to “families, people with children.” “The last thing I heard from them was, ‘¡Vámonos!’ ”

As the son of an Italian who “didn’t speak a word of English when he came over,” Figliola could empathize. The problem was capturing immigrants’ plight in a way he could paint. He did extensive research into photos of actual crossings but decided their look wasn’t quite right. When he invited immigrants to his studio to model for him, however, people mistook it for an opportunity to get glamour shots. One woman “showed up, if you would believe this, in a low-cut evening dress— with big bazooms!” Figliola says in his colorful New York Italian accent. “You couldn’t get around the idea that she really wanted a Hollywood kind of picture.”

And so, in one of reality’s little ironies, the subjects borrowed clothes from the Figliolas’ own closet to get their wardrobe right. He photographed them in various dramatic poses, then assembled groups to fill panoramas of creosote and caliche rendered in meticulous detail. Superreal? Hardly. But the paintings, which were shown at the international Ciudad Juárez–El Paso Biennial, were a success—Figliola had hit on humanity.

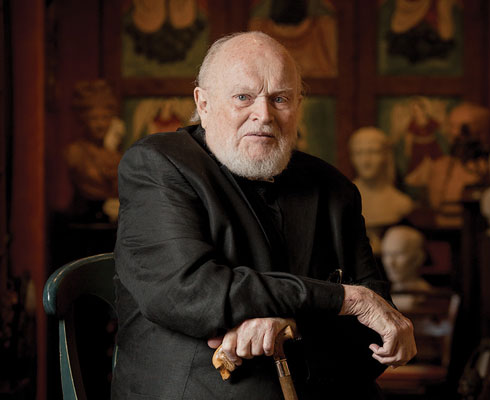

Opera patron Edgar Foster Daniels at home in Santa Fe.

Opera patron Edgar Foster Daniels at home in Santa Fe.

Photo by Minesh Bacrania.

THE OPERAPHILE

As a student at Columbia University in the fifties, Edgar Foster Daniels made two acquaintances that would change his life. The first—and dearest—was the Metropolitan Opera. “Whenever I was not working I’d go there,” he says. After graduation he moved to Los Angeles to act for the screen, but at the time that city had no opera, and he pined for the productions that had moved him at the Met.

The other acquaintance, a classmate named John Crosby, never lost touch with the art form they both loved. By 1958 he had founded the Santa Fe Opera and invited his friend out to see the second season. Daniels became a devotee of the company, and 20 years later moved to Santa Fe. When he inherited money from a family newspaper business, he began to fund as many productions as he could. He served on the boards of both the Santa Fe Opera and the Met, chipped in for air-conditioning in Salzburg, where he makes annual visits for Wagner, and became a prominent patron of music and visual arts. Nancy Zeckendorf, a past Governor’s Award recipient, calls Daniels “a lifelong supporter of the arts in Santa Fe.”

Now wheelchair-bound, Daniels still manages frequent visits to the Santa Fe Opera. During a recent phone interview he expressed excitement for the summer’s staging of Cold Mountain, while in the background a tenor dipped and soared. Asked what CD he was playing, he listened for a moment, then showed off an aficionado’s ear. “It’s a Rossini opera. I think the singer is Juan Diego Flórez. It’s on the radio.”

EXHIBITIONS

There are distinct advantages to attending one of New Mexico’s many exceptional artist studio tour weekends (newmexico.org/studio-tours) in a small community like El Rito (pop. 800). “We have 18 stops and 34 artists,” says painter and tour organizer Jan Bachman, “but the town is compact—you can walk to many of them.” Don’t miss the town’s lone eatery, El Farolito, a friendly, down-home spot that’s developed a fanatical following for its green chile stew.

Bachman moved to this village fringing the southern Tusas Mountains a few years ago from Colorado with her husband, photographer Tom Quinn Kumpf. “We had heard about some of the artists here,” says Bachman. They came to visit and found that they “just had to stay—we bought a house and put two studios on the property.” You can meet both artists during the El Rito Studio Tour, Oct. 3–4 (575-581-4679, elritostudiotour.org). The Abiquiú Studio Tour takes place just 15 miles away on Oct. 10–12 (505-685-4770; abiquiustudiotour.org).

The Galisteo Studio Tour (Oct. 17–18) includes a stop at 2014 Governor’s Award– winning artist Jean Anaya Moya’s studio (galisteostudiotour.com). Silver City’s Red Dot Studio/Gallery Festival ups the ante with a two-weekend run and robust gallery participation Oct. 10–12 and 17–18. (575) 313-9631; silvercitygalleries.com

—Andrew Collins