Andy Sanchez has a royal claim to fame unlike most custom furniture builders. Not only did King Carlos of Spain sip tea at one of his five tables in Patrick Mavros’ London gallery, but so did England’s Queen Elizabeth herself. Sánchez, however, has garnered so many accolades that such occurrences are just the icing on the cake.

Sánchez’s pieces range in size from a nightstand to a boardroom conference table. His artistic blending of sliced gemstones and fossils inlaid in knotholes is one distinguishing feature of his style.

“As an artist,” Sánchez reflects, “my canvas has been painted. My job is to orchestrate—to bring the slabs of wood and stone together in the right proportion.”

Sánchez describes his inlaid pieces as “a delight to touch. They feel like satin.”

Customers often specify particular inlay designs—an elk head silhouette, a deer footprint—which he creates with stone and copper. Other times, the stone determines the design, such as the agate sea turtle in a coffee table that graces a Placitas home.

“As you work,” Sánchez adds, “the slab and stones can change your vision. It’s exciting to see what will happen. Another thrill arrives when a piece is finally oiled— to actually see what it will look like. When I first started, my entire family would gather for the final oiling, just because that’s when the beauty of the wood appeared.”

A piece by Andy Sánchez of alligator juniper with stone inlays, including an ammonite fossil, turquoise, and marble.

A piece by Andy Sánchez of alligator juniper with stone inlays, including an ammonite fossil, turquoise, and marble.Like any artist, Sánchez was influenced and inspired by the work of others. George Nakashima was, according to Sánchez, “the first furniture artist bold enough to do live edge,” allowing the natural contours of the wood slab to define the piece. James Krenov inspired Sánchez to work with split slabs of wood joined to form a larger slab with mirror-image grains, and spalted wood, intricately patterned by bacteria.

However, one of Sánchez’s strongest trademarks is his frequent use of burled redwood and alligator juniper. He says that a hundred years ago, there was no market for redwood burls, so they were used as fill for logging roads—buried and ultimately stained as mineral-filled water seeped through the soil. Today, these dark burgundy burls are repurposed by Sánchez for exquisite furniture. Some burls are two thousand years old.

Half as old are intricately swirled dead alligator juniper slabs from the Gila National Forest. “It’s like being given a trust,” says Sánchez, “to work with something over a thousand years old. The history they represent gives me a thrill.”

Sánchez’s work has garnered awards at art shows in Sedona, Arizona; Indian Wells, California; and Cody, Wyoming. He also travels to Tucson’s annual Mineral, Fossil & Gem Show to stock up on the jewelry-grade gemstones and fossils that embellish his Western-styled work.

His work is fulfilling, but his deep New Mexican roots keep him grounded. On his paternal side, an ancestral grandfather, Remaldo, fled the Spanish Inquisition in the early 1700s to settle east of Belén. His mother’s father was half Isleta Puebloan, and her mother was half Comanche.

Sánchez moved to the East Coast in 1986 to begin his career as a cabinetmaker. It wasn’t until he spent two years working on a home in Maryland with no time or budget limits that he realized he had the patience and attention to detail needed to build custom furniture. He moved back to Belén in 1989, and then to Algodones 11 years ago.

Two of his four sons, Aaron and Daniel, have been inspired to work alongside their father in his spacious shop. A diamond saw for slicing gems and fossils sits near boxes of turquoise and agates. In between are high tables supporting works in progress, along with chisels, copping saws, and calipers. The rafters hold entwined elk horns, while the marble, redwood and juniper slabs, and twisted roots for bases are stacked outdoors. Local and out-of-state customers are encouraged to visit the studio so that they can select the stones, slabs, and bases that appeal to them—a level of wish fulfillment fit for a king.

—Dorothy Noe

Andy and Aaron Sánchez Furniture

4 Archibeque Drive, Algodones

(505) 385-1189; andysanchez.com

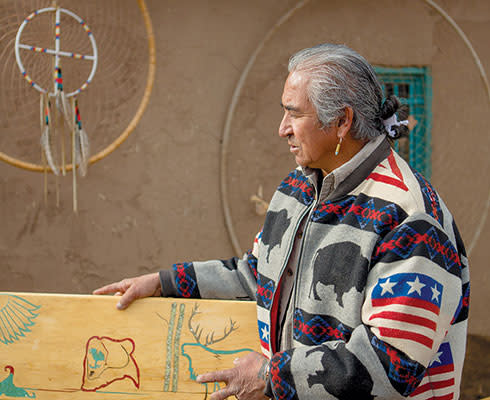

If you're walking around Taos Pueblo, freshly blissed out by the beauty of the adobe village and the mountain vistas, you may think you are completely incapable of taking in one more mesmerizing experience. But you should try. Because as you walk past the House of Water Crow Studio Gallery, Carpio Bernal might come out and say hello—and he just might be one of the most interesting people in New Mexico.

When Carpio was five years old, tourists who heard him singing a song gave him two nickels each. “It opened my eyes on how to make money,” he says. Soon after that, as he walked across the Pueblo with a bow and arrow and a tomahawk that he’d made, tourists asked if they could buy them, and he sold them, happily. He made them with his grandfather, who, along with his grandmother, raised him. “I grew up traditionally, and speak fluent Tiwa,” says Carpio. “My grandparents were my teachers and inspired me to grow. I have a lot to thank them for; it’s embedded in my heart.”

Before producing fine inlay custom furniture (which features animal imagery, abstract designs, and geometric shapes formed by turquoise, coral, lapis, and sugilite), Bernal was part of the first Native American theater ensemble in New York City, at La MaMa Theatre in 1970, and moved to Washington State as a woodworking apprentice under his “spiritual father and teacher,” Bruce Miller, until 1984. He met his wife, Rose (a singer—and not just of Carpio’s praises), in the Pacific Northwest and returned with her to Taos Pueblo. In between New York and Washington, he came home and acted in a comedy film called The Human Highway, starring Dennis Hopper, Dean Stockwell, and Neil Young. He acted in other films with Kris Kristofferson and Kenny Rogers.

His father, Paul Bernal, “was the first Native to ever win land back for Native people—he fought for Blue Lake.” As council secretary, Paul and Taos Pueblo’s religious leader, Juan de Jesus Romero, worked to negotiate an agreement with the federal government—48,000 acres were returned to the Pueblo as a result.

The lineage of movers, shakers, and makers continues to this day. “We have a family business,” he says. Four of his children contribute artwork to the gallery, which sells silver jewelry, baskets, drums, and Carpio’s furniture. The family also has a recording studio, where Rose is working on an album.

One of his more popular pieces is a slim, angled “chakra chair” that encourages the sitter to lean back, align his or her spine and neck, and relax. “People love it— they’re healing,” he says. “I often inlay an eagle figure, because the eagle is a powerful healer. Everything I do is from my heart. I catch my artwork from the wind, put it in my mind, use it, then let it go into the wind again and pass it on.”

Sitting in the chair, wind gently blowing your hair as you stare at Taos Pueblo’s buildings and blue sky, it all makes perfect sense.

—Candace Walsh

House of Water Crow Studio Gallery

133 White Rock Rd., Taos Pueblo

(575) 770-7856; on Facebook