JAMES CAMERON'S EFFECTS-LADEN TITANIC was 1997’s biggest box-office smash, sailing into the 70th Academy Awards with 14 nominations and expectations the size of icebergs. The film won all but three of those statues, and tied a record that had stood for 38 years; until Titanic, no other film could match Ben-Hur at the Oscars. And, while the 1959 film never shot a day in New Mexico, the story came to life on the Santa Fe Plaza. If General Lew Wallace, the author of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, came to the Territory of New Mexico in 1878 in search of a writer’s retreat, he came to the wrong place. Range wars ripped the territory into pieces. The U.S. Army struggled to suppress local Apaches while a consortium of corrupt businessmen dominated the region and almost all of its commercial interests.

Wallace had survived worse. When he was a young general during the Civil War, he made his regiment late for the Battle of Shiloh, which the Union won despite enduring heavy losses of life. The mistake cost Wallace his command and damaged his reputation. The stigma stuck with Wallace even as he went on to sit on the tribunal for Lincoln’s assassination, and to a later career as a lawyer in his native Indiana.

When the drama subsided, Wallace grew bored by his life in Indiana. His law practice and occasional forays into government failed to match his ambitions. Fortunately, Wallace had a big favor coming from President Rutherford B. Hayes. As thanks for helping Hayes in Indiana during the election, Hayes gave Wallace a choice between two positions: territorial governorship of New Mexico, or delegate to Bolivia. Wallace knew almost nothing about either place, but chose New Mexico. Maybe he thought it would resemble old Mexico. He had participated in the invasion of the country during the U.S.-Mexican War, and used the experience as the basis for his first novel.

The move to New Mexico set the tone for Wallace’s tenure. It was a few years prior to the installation of the rail to Santa Fe, and he traveled by wagon from Trinidad, Colorado. The primitive suspension on the carriage did little to cushion the bumpy trail. “A deadlier instrument of torture was never used in the days of Torquemada,” he wrote in a letter to his wife, Susan, describing the journey.

Conditions in the territory shocked him. The adobe of the ancient Palace of the Governors building had received relatively little upkeep prior to Wallace’s arrival, and the structure’s contents had been neglected, too. He and his wife, who had joined him, found a pile of rotting papers in the back of the old building and recognized their importance almost immediately; those papers would eventually become the Spanish Archives of New Mexico.

Worse yet, Wallace received a very cold welcome from his predecessor. As territorial governor, Samuel B. Axtell used his position to better his business affairs, and consequently those of a loose cohort of like-minded entrepreneurs called the Santa Fe Ring. Its members ran an intricate vertical-control scheme in which they exercised political power to manipulate cattle, land, and retail operations in the territory. Members of the ring, including Axtell, were none too happy about Wallace’s inauguration.

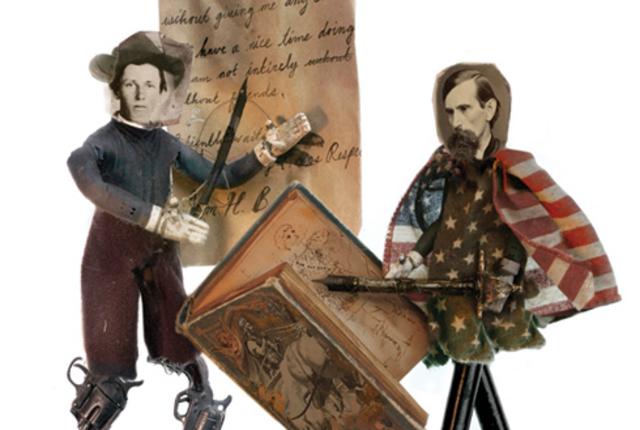

But the ring created its own troubles. A few of its associates, Lincoln County mercantilists named Murphy and Dolan, allowed their scheme to become national news. Their established storefront, The House, enjoyed a virtual monopoly on sales of goods and lucrative government beef contracts, until John Tunstall arrived in the area and created a rival enterprise. Tunstall hired a few ranch hands with special talents to protect him from the House. One of those young men, William H. Bonney, aka Billy the Kid, went on to become the most famous soldier in the resulting Lincoln County War.

THE FIGHTING BETWEEN TUNSTALL’S GROUP and the House captured the popular imagination, becoming fodder for newspapers and dime novels. But for the federal government, it was an embarrassment. More than a decade after the Civil War, it did not want to appear unable to control an unruly bunch of cowboys, much less the nearby “insurgent” Apaches. Wallace was assigned to cleanup duty. Reluctant to embroil himself with the powerful ring, Wallace responded with diplomacy. He issued a general pardon to everyone who had participated in the war, a blanket exoneration for a slew of rather violent individuals. Only those with preexisting infractions would not be excused; chief among them was Billy the Kid.

The Kid wrote to Wallace in search of a pardon. “I have heard that you will give one thousand $ dollars which as I can understand it means alive as a Witness … but I have indictments against me for things that happened in the late Lincoln County War and am afraid to give up because my enemies would kill me.”

Wallace responded, and so the strangest pair of pen pals in New Mexico history was born. The governor even convinced the Kid to help capture criminals. The two met secretly in Lincoln County and agreed that the Kid would testify against other local do-badders in exchange for exoneration. Afterwards, the Kid repeatedly wrote Wallace, begging for the pardon that Wallace promised him at that rendezvous. The pleas fell upon deaf ears. Wallace stopped responding to the letters and, on December 13, 1880, he issued a warrant for the Kid’s arrest— the same warrant that led Sheriff Pat Garrett to shoot Billy the Kid dead in Fort Sumner in 1881.

Wallace had lost interest in the Kid long before his death. For the general, outlaws posed less of a threat to the territory than the Apaches. Victorio, a chief of the Chihenne band of the Chiricahua Apaches, and his fellow tribesmen in the southern part of New Mexico, proved increasingly difficult for the American Army to corral. Only after Victorio trapped himself between Mexican and American forces along the border did his impressive resilience come to an end. “Now that Victorio is dead, this Territory is peaceful,” Wallace said.

Wallace had other troubles in the south. He invested in a series of mines near Silver City. “I have held the office [of governor] until I have accomplished what I wanted the acquirement of which I consider good mining property as there is in the territory,” he wrote to his son. But the mines proved unprofitable, depriving Wallace of what was perhaps his single greatest interest in New Mexico.

THE TERRITORY MAY HAVE FAILED to provide for Wallace, but he had plans for making it on his own. Prior to arriving in New Mexico, Wallace had begun working on his second novel, which was inspired by a serendipitous meeting on a train with the nation’s most famous agnostic, Robert Ingersoll. Wallace’s conversation with Ingersoll motivated him to explore faith and the life of Christ in his new book, a grand and sweeping tale that began with the magi and ended with salvation through Christ. Much of it had been written before Wallace set foot in New Mexico, so he had only a few chapters to complete in the territory.

On rare days, he would devote 12 full hours to writing. But the demands of the governorship often meant Wallace could only make time to write at night. The process was hectic. He paced around the Palace scribbling notes as he went, and pored over the many revisions and suggestions sent to him by his wife, who had returned to their home in Indiana. He wrote in a Plaza-facing room, or he’d hide. “Once there, at my rough pitch table, the Count of Monte Cristo was not more lost to the world,” he later wrote of one of his spots. Some reports insist that he would close the blinds to keep his exact location a secret from the revenge-minded Billy the Kid.

Ben-Hur is a massive tome, and Wallace devoted a great deal of time to keeping the details straight. He finished the book in March of 1880. Not long after, he followed his manuscript to New York, where he met with Harper & Brothers, which published the novel despite wariness of its religious overtones. At first, the book did not sell particularly well. Within a few years, however, Ben- Hur would gain an audience.

James Garfield, the incoming president, joined legions of readers who admired the book, but he had a singular reaction to the novel—he reassigned Wallace to the consulate of Turkey. What better post for the author of such a sweeping epic? Moreover, Wallace could use the time in Turkey to complete another novel.

The new assignment also meant that Wallace could finally escape New Mexico. He would ultimately deliver this famous, biting verdict of the state: “Every calculation based on experience elsewhere fails in New Mexico.”

Susan’s swing at the territory was even more vitriolic. She wrote, “We should have another war with Old Mexico to make her take back New Mexico.”

THE SUCCESS OF BEN-HUR swept away any lingering troubles Wallace might have retained from New Mexico. It would eventually become one of the best-selling novels of the 19th and early 20th centuries, attracting interest from stage producers in New York. Wallace rebuffed them until finally consenting to put the book on stage in 1889. The production of Ben-Hur raised the bar for staged effects. To re-create the integral chariot race, it used a sort of treadmill on which horses trotted. Unfortunately for the producers, the horses rarely went by the script, and the wrong charioteer would sometimes finish first.

Wallace lived long enough to see his beloved novel become a success on stage, but not on the screen. In 1905, he died of stomach cancer at the age of 77 in his home in Crawsfordville, Indiana. As he lay in his study, hundreds of people came to pay their respects. A passage from Ben-Hur was inscribed on his headstone. Susan would soon finish and publish his autobiography, but his true legacy was about to gain an even wider audience.

An infantile Hollywood took notice of the literary and theatrical spectacles, and rallied to put Ben-Hur on film in 1907. The producers neglected to compensate the Wallace family for use of Lew’s intellectual property, and the Wallace family took legal action. The case reached the Supreme Court, and eventually set precedent for copyright laws still in use. Fortunately for the Wallace family, the judges ruled in its favor. Ben-Hur still had profitable days ahead.

Filmmakers attempted to board the chariot again in the early 1920s. It wasn’t just the horses that ran wild this time, though— the entire film went off track. It was scheduled to shoot in Italy, and production costs skyrocketed. Louis B. Mayer, then head of production for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, pulled in the reins. He threw away much of the footage, brought the film back to California, and selected Ramon Navarro to be the film’s new lead.

Mayer’s intuitions were validated as Ben-Hur brought in $9 million in ticket sales. It fit squarely into the golden age of silent films and, along with many other movies, propelled Hollywood through two decades of growth. But by the 1950s, a competitor threatened the silver screen—television. The major film studios wanted spectacular cinema that could not be replicated in living rooms. They turned, once again, to Lew Wallace. Not only did Ben-Hur promise action and scenery too large for the television screen, but the story offered a distinct fringe benefit— religious overtones. Hollywood took a beating in the 1950s at the hands of Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee. The Communist-hunting tribunal blacklisted a number of filmmaking elites, and gave the entire industry a black eye. A successful adaptation of Wallace’s classic would shore up both MGM’s bottom line and public image.

Two-time Academy Award winner William Wyler was hired to direct the film. Charlton Heston, a veteran of another biblical blockbuster, was brought on board to be the film’s star. Although he had a few reservations about the project, Heston wrote in his production journal, “The picture itself in Willie’s hands looks pretty staggering.” That was putting it mildly. It took more than a year to construct the film’s 300 sets, 1 million props, 18 chariots, and 20 ships. One hundred seamstresses were employed to sew the multitude of costumes, while 15,000 extras populated the stands during the chariot race. The investment of time and money provided a huge return. The film made $80 million at the box office, and the number of Oscars it received set a record that lasted for decades.

The chariot ride, however, has yet to end. A straight-to-video miniseries of Ben-Hur was released in 2010. MGM now has plans for another version of the epic, to be helmed by the Russian director Timur Bekmambetov. This would be the first big-screen version of the film to include computer-generated imagery. Bekmambetov has a reputation for stunning visuals like those that appear in his latest efforts, Wanted and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter. This new take on Ben-Hur focuses on Judah Ben-Hur and his Roman friend and betrayer, Messala. John Ridley, who wrote the Academy Award–winning adaptation of 12 Years a Slave, authored the most recent screenplay. The extremely successful novel that was partially written in New Mexico will reach a whole new generation.

But while Judah Ben-Hur may reappear on screen from time to time, he has yet to achieve the same legendary status as Wallace’s one-time collaborator, Billy the Kid. The gunslinger, cut down in his early 20s, is the most famous of Wild West outlaws and has been the focus of dozens of films, including Young Guns, Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, and The Left Handed Gun. In a case of irony an author might best appreciate, Wallace may ultimately be most remembered as the man who betrayed Billy the Kid, and not as a Civil War general, territorial governor, or best-selling author. ✜