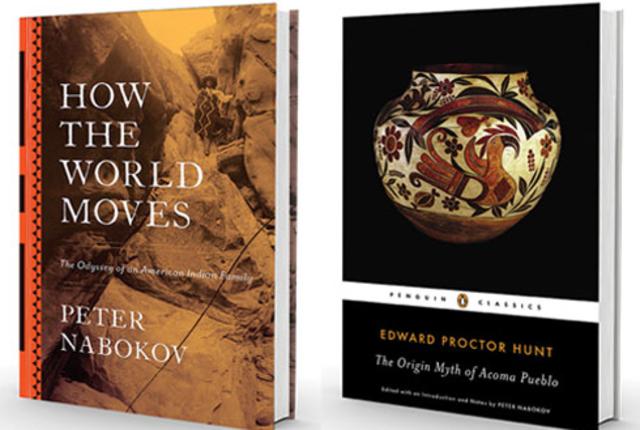

HOW THE WORLD MOVES: The Odyssey of an American Indian Family

BY PETER NABOKOV

(Viking, 2015)

THE ORIGIN MYTH OF ACOMA PUEBLO

BY EDWARD PROCTOR HUNT

(Penguin, 2015)

Peter Nabokov is no stranger to Native America. The UCLA professor addressed the subject of Native American religion in his last book. In his new one, he studies one family—one man—to open a particular window to the Native American experience of the past 150 years.

How the World Moves is about Edward Proctor Hunt and his family and their sometimes tortured relationship with their pueblo: Acoma. And although Hunt’s voyage from Pueblo to frontier marketplace to European circuses to Washington and then back “home” again wasn’t unprecedented, it was his decision to reveal to outsiders the founding story of his Pueblo that makes him a particularly interesting (and controversial) subject.

Born as Day Break to an Acoma medicine man and his wife in 1861, Hunt spent his early years in preparation for a life at the heart of his Pueblo’s spiritual and cultural service. In 1880, he was sent off to the Albuquerque Indian School. There, everything began to change. First, Day Break adopted the name Edward Proctor Hunt, which he got from the inscription in a Bible he found in a donated coat. Then, like many young men, he was seduced by a worldview and sense of the future utterly at odds with his upbringing, and found he was no longer wholly comfortable in the kivas and housing blocks of his birth.

After leaving school, and unable to reconcile his Christian beliefs with those of his people or handle the implications, Hunt left Acoma and went into the mercantile business in nearby Acomita. There he became an Indian running an Indian trading post—an unusual arrangement.

In the late 1920s, after failing to make a home at Santa Ana Pueblo, Hunt and his wife, Maria, and son Wilber joined a Wild West show and represented a Native stereotype of the period: the warbonnet-wearing, whooping Plains Indian. He mastered and dramatized the role, and for years afterward, both in Europe and the United States, he played a fictionalized iteration of the noble savage called Big Snake.

It was during a break in this work that Hunt and his family went to the Smithsonian and he told the story for which he is most famous. It took two months, during which time he sang the songs of Acoma, told the secret stories, and broke the deepest of Acoma’s contracts with its people, which Nabokov summarizes as “daring to be from it but no longer in it.”

By the 1930s, he and his family were back in the Southwest and regularly leading the Gallup Inter-Tribal march, but he never really returned to Acoma. He died in 1948 and is buried in Albuquerque. His children carried on as craftspeople and as advocates for the sort of inclusive world that Hunt had always sought.

As was typical, when Hunt’s version of the Acoma origin myth was first published, in 1942, neither his name nor those of his two collaborator sons—Wilber and Henry—were anywhere to be found. Furthermore, the transcribers as well as the document’s later editors (who included the legendary anthropologist Franz Boas) were men of their times. Stories or explanations they considered unimportant were left out, and preferred meanings and explanations undoubtedly replaced some of those originally intended. The new edition of The Origin Myth of Acoma Pueblo, edited by Nabokov, was issued as a companion piece to his new book. Heavily drawing from his conversations with Wilber, Nabokov sought to improve its accuracy.

The conversational style that permeates the record—Hunt’s voice—makes it a far cry from the usual classic academic recitation of an origin myth and makes for compelling reading. This is a trait it shares with Nabokov’s How the World Moves.

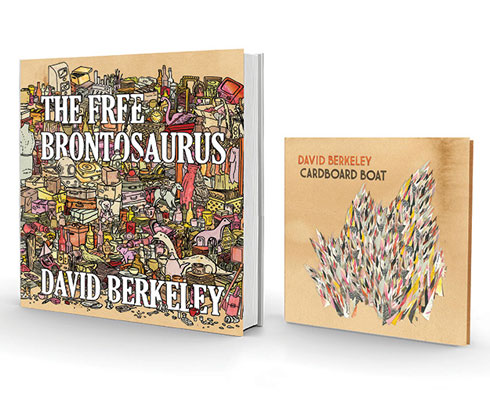

THE FREE BRONTOSAURUS

(Rare Bird, 2015)

CARDBOARD BOAT

(Straw Man, 2015)

BY DAVID BERKELEY

When did America’s singer-songwriters start moonlighting as writer-writers? For a certain indie-folk type, a side gig in fiction has become as obligatory as a train song: The Mountain Goats’ John Darnielle and the Decemberists’ Colin Meloy (among others) have published well-received novels recently.

Santa Fe’s David Berkeley is a less flashy lyricist than those two, but his new book, The Free Brontosaurus (Rare Bird), has literary ambition to burn. Each story in the linked collection corresponds to a companion track on Berkeley’s latest record, Cardboard Boat (Straw Man), whose ten songs are narrated by the book’s nine protagonists. Call it a high-concept album or lit-fic with a soundtrack—whatever it is, the dual project feels like the logical endpoint of folkie fiction.

Berkeley’s empathic range keeps the whole thing grounded. Songs whose first-person pronouns might otherwise bleed together into the voice of a sensitive thirty-something musician break apart, with the help of The Free Brontosaurus, into a chorus of Raymond Carverish lonely souls—a widowed grandmother, a washed-up sailor, an angry artist—adrift in a port city. When Berkeley sings, “There is a river running through my bones,” it’s not just a personal metaphor; it recalls a character’s wild tale about being born on a raft in Hells Canyon.

Water is everywhere in Cardboard Boat, which suits Berkeley’s music. Spare acoustic verses rise on the tide of his breathy baritone, then crest into yearning choruses driven by Will Robertson’s string arrangements and harmonies from Nickel Creek’s Sara Watkins. If not for the liner note that Jono Manson engineered and mixed the record at his Kitchen Sink Studios in Chupadero, it’d be easy to forget that songs like “Setting Sail” and “To the Sea” are anchored in a landlocked desert state. How’s that for musical fiction?