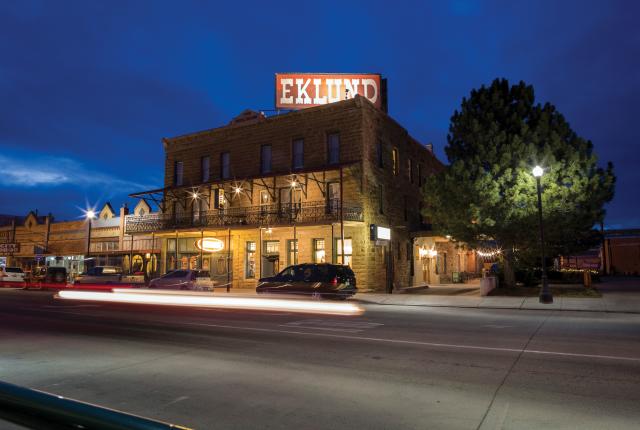

Above: The Eklund Hotel in Clayton. Photographs by Gabriella Marks.

WITH ITS COVEY OF COWBOY HATS, ranches, and prairie stillness, Clayton and its 2,763 residents exude a clear-cut Americana.

Rabbit Ears Mountain, that conspicuous rock formation to the north, looms over this one-stoplight town. Founded with a railroad station along what had been the Santa Fe Trail, it grew into an important cattle-shipping hub for the western fringes of the Great Plains, in the northeast corner of New Mexico, near its intersection with Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas.

Like much of rural America, it’s shrunk a bit—in 1950, it peaked at 3,515 residents. The Luna Theater, built in 1916 and still topped by a smiling neon moon, thrived in those years. That kind of stability cratered when the Dust Bowl descended. In May 1937, a black cloud 1,500 feet high and a mile wide enshrouded the town, dropping more than 300,000 tons of dirt.

Among those who stayed to dig out, a strand of gritty pluck emerged. With help from the Works Progress Administration, community members reinvented their town. They built a new Clayton School, which opened in 1938 as a before-its-time maker space—a regional vocational program that trained students to create fine art, pottery, textiles, and wooden furniture and work with wrought iron and copper. Their impressive output forms part of the country’s largest collection of WPA art, gathered at the Herzstein Memorial Museum, named for the family of Jewish settlers and entrepreneurs who built the Luna Theater.

Now the descendants of those survivors have joined hands with enthusiastic newcomers to tap into the town’s legacy and reinvent Clayton once again.

Above: Victoria Baker, the executive director of the Herzstein Memorial Museum, has brought new life to the museum and the town.

Above: Victoria Baker, the executive director of the Herzstein Memorial Museum, has brought new life to the museum and the town.

THE LEADER

Victoria Baker is a bright-eyed, never-stops-moving woman leading the charge to revitalize downtown commerce. Her plan is for this seat of Union County to not necessarily get bigger, but most certainly to get better. She came into this world 55 years ago on a ranch in nearby Barney, which has since turned into a ghost town. At 18, she decided there was nothing to keep her there. “I thought Clayton was, well, pretty provincial,” she says. “I wanted to go to a larger town, where I could accomplish a lot.”

She settled in Denver and made a life there for nearly three decades, but in 2000, recently divorced, she headed back to New Mexico with her two young daughters. “My idea was to regroup here, but not to stay,” she says.

But then she came to like the idea of her daughters growing up on a ranch, as she had done. She married a rancher whom she had looked up to as a youngster. “He was seven years older than I was, but every girl in town was in love with him,” she says.

It took a little while, but she eventually found her place—as executive director of the Herzstein Museum, set in a former church and holding, legend says, a basement ghost. She threw herself into the job. Travelers who happen by the museum will hear her urge them to spend more time in a town that likes to say it is the center of the universe. Her energy is powerful and contagious. More than one local describes her as “a force.”

Baker has earned support from old-timers and some newcomers who pick up on her enthusiasm. Many are connected through the museum, working to promote the WPA collection and update the displays of pioneer artifacts and Dust Bowl devastation. But nothing tells the history of Clayton quite as well as the folks who are writing its future.

Above: Susan Ernsberger moved to Clayton and bought the house her great-grandmother lived in nearly 100 years ago.

Above: Susan Ernsberger moved to Clayton and bought the house her great-grandmother lived in nearly 100 years ago.

THE TRANSPLANT

At the dawn of the 1900s, Susan Ernsberger’s great-grandmother, a boot-tough Ohioan named Sarah Faris, decided to homestead in rugged Union County. Faris experienced fierce droughts, her well went dry, and snow fell hard. A widow, she’d soon had enough of that life. She sold the homestead, rode into Clayton on horseback, and bought a small house on Oak Street, where she died in 1930.

Ernsberger grew up in Cincinnati. In 2012, almost 80 years after her great-grandmother’s death, she and her mother, who were then living in Albuquerque, made a spur-of-the-moment visit to Clayton. They stopped by the cemetery where Faris is buried and then found her old house. “It was so tiny, I thought it was an outbuilding,” Ernsberger says.

After she left, something about Clayton tugged at her. Five years ago, she moved to Clayton—into the little house once owned by her great-grandmother. Initially, she felt like an outsider in Clayton, but that changed as she began painting and meeting other artists in the community. She also joined the board of directors of the museum.

Now, whenever this ex-Cincinnatian strolls about her small yard or walks the floor inside her teeny house, she says she feels the presence of Sarah Faris. “How strong and sturdy she must have been!” she says. “That’s what really connected me to Clayton. And that’s why I am going to stay here.”

Above: Bess Isaacs and her prime view of Main Street.

Above: Bess Isaacs and her prime view of Main Street.

THE STALWART

When Bess Isaacs married Bob Isaacs, she joined him in the town’s hardware store, now True Value Hardware, where her desk has always faced a window on Main Street. “Well, somebody’s got to watch what’s going on out there,” she says.

Bess was born in Clayton in 1925, delivered by her father, Dr. James McNeil Winchester, the town physician. “Doctor Mac” traveled by horseback to see patients. If young Bess wanted to go along, and she usually did, he would put her in a horse and buggy. Otherwise, she walked everywhere.

She still does. From her hardware store window she shakes her head at people who get in their cars to drive a single block. At 93, she hoofs it to the bank or to the post office. Her strong will and determined nature are characteristic of Claytonites. “What’s my secret?” she asks. “I don’t stay home. If I did, I’d have to clean house, and who wants to do that?”

Although very much a stalwart of a bygone age, Isaacs knows that Clayton is changing—and she likes it. “Victoria [Baker] has done wonders here,” she says. “She’s encouraged everybody to come and be part of what she is doing.”

Above: Craig Reeves at his family's bank.

Above: Craig Reeves at his family's bank.

THE BANKER

Craig Reeves was born in Amarillo, but he calls Clayton home. After graduating from Clayton High School, he took off for Albuquerque, where, in 1984, he obtained a business degree from the University of New Mexico. A few months later, he took a job with a bank in Amarillo, 130 miles southeast of Clayton. Meanwhile, his parents, also bankers, had turned the town’s First National Bank into a mom-and-pop operation. When they asked their son to come home and join them, he didn’t hesitate.

“I just fell in love with the people here,” he says. “Now I’ve been with the bank 31 years, and I don’t plan on working anywhere else.”

After Reeves came on board, the family added shareholders and strengthened the bank’s foundation enough to expand. Now chartered as FNB New Mexico, they added locations in Ratón, Angel Fire, Santa Rosa, Tucumcari, and Logan. Think about that: The town shrank, but the bank grew, and Reeves sees that possibility for others here. “We need to tell people what a great place Clayton is to live and work,” he says. “We want people to stop here, not just motor through.”

Above: Keith Barras and Jeanette Vigil Vargas run the Eklund Hotel, one of the institutions essential to Clayton's revitalization.

THE INNKEEPER

Born in Clovis, Jeannette Vigil Vargas lived in Clayton for most of her youth. As an architecture student at UNM, she met her future husband, Keith Barras, and they settled first in Albuquerque, then Los Alamos. In 2012, they relocated to Clayton. The Hotel Eklund, originally built in 1892, had been closed for three years. The stately landmark with a Wild West past hadn’t aged well. Vargas, her husband, and a few business partners agreed to renovate and reopen it.

Vargas takes pride that she helped get the hotel up and running again. “This is my home, my life,” she says. “Coming back to Clayton was a real change of pace. I am busier here than I ever was. The Eklund is still the go-to place. I want this town to improve and to keep on improving.”

ON THE TOWN

The Herzstein Memorial Museum’s exhibits cover the area’s history, from dinosaur tracks to the Santa Fe Trail, the Dust Bowl, WPA art, and a model railroad scene. It’s open Tuesday–Saturday for free (22 S. 2nd St., 575-374-2977, on Facebook).

The Hotel Eklund’s 24 guest rooms and suites include some with balconies. Two dining rooms and a stand-alone bar with bullet holes in the wall behind it paint a true Wild West picture. The saloon also features the legend of train robber Black Jack Ketchum, who was hanged in Clayton in 1901 (15 Main St., 575-374-2551, hoteleklund.com).

The Luna Theater, a grand old cinema built in 1916, is a downtown icon. Renovated in 2013, it shows a different movie every week, Friday–Sunday evenings (4 Main St., 575-373-8331).

Mock’s Crossroads Coffee Mill inhabits a solid brick building that once was a feed store. Drink a cup or two here, because the nearest coffee shop is 83 miles away. Owners Rustin and Jennifer Mock, Clayton natives, roast their coffee beans on-site. If you’re pressed for time, there’s even a drive-through window. Open Monday–Saturday (2 S. Front St., 575-374-5282, mocksmill.com).

The Rabbit Ear Café continues a Clayton tradition that dates back to 1962. Try the specialty sopa burger (a hamburger patty sandwiched between two sopaipillas instead of a bun) for lunch or dinner, Tuesday–Saturday (1201 N. 1st St., 575-374-3277).

Cissy’s Closet, a consignment and gift shop, recently filled the old VFW building with an eclectic selection of clothes and vintage items. Clayton native Cissy Brown is the offbeat star of the enterprise. Open Tuesday–Saturday (106 S. 1st St., on Facebook).