Above: Cara Romero. Photograph by Gabriella Marks.

IT FEELS LIKE A DREAM. Water surges in all directions, topaz in color and faceted by the rays of an unknown source of light. The scene is chilling and beautiful at the same time, almost too elusive for an easy conclusion. Are the two figures—Santa Clara Pueblo corn dancers—drowning? Floating? Pushed into the current? Or are they alive, immersed but still breathing because some otherworldly force wills it? The questions cascade much like the flood of water that takes up the entirety of the photograph. It’s both mythical and apocalyptic.

This is Cara Romero’s Water Memory, from 2015, a large 30-by-30-inch mounted archival pigment photograph, part of a series that includes Eufaula Girls and Oil Boom, each of which broaches twin histories: the flooding of tribal lands to construct U.S. dams; and the pumping of resources from Native soils by extractive industries.

“Visually, the photograph was strong, because it could be so many things,” Romero says of Water Memory. “It draws out that universal thread of the Great Flood. But I’m also from a tribe that was flooded out of ancestral lands—the Army Corps of Engineers actually forcefully dragged people out of their homes to create Lake Havasu. The oral histories tell of how there were already inches of water in people’s homes before they were made to leave. Now Lake Havasu feels haunted—there are homes and floodplains below—and when I submerge myself there, I feel all that water memory.”

Water Memory proved pivotal for Romero, who grew up in the Chemehuevi Valley Indian Reservation, along the California shoreline of Lake Havasu, the daughter of a Chemehuevi father and a German-Irish mother. “It brought outcomes I never imagined possible, like the Smithsonian collecting my work,” she says. “After that, my art became an examination of things that were important to me—things that scared me but that I knew to be true. I started working with female figures. I wanted to break through the exploitative white-male lens that had dominated Native American photography for over a hundred years.”

As an undergraduate at the University of Houston, Romero pursued a degree in cultural anthropology. After realizing that photographs could do more than anthropology did in words, she shifted her medium, first to reportage and then fine art. “I came from poverty, and having an aesthetic medium, like photography, which can be very expensive to make, felt frivolous,” she says of the switch. “But Water Memory paid for itself 20 times over. And more than that, it was affirming for me as a woman to feel smart and capable to invest in my art and my business.” Romero now lives in Santa Fe with her husband, the celebrated potter Diego Romero, of Cochiti Pueblo, and two sons, Paris and Noel.

Peters Projects, in Santa Fe, recently exhibited her photography in Everywhen: Indigenous Photoscapes. The National Museum of the American Indian, the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, and the American Museum of Britain all hold her work in their collections. She has also won multiple first-place awards at Santa Fe Indian Market. And as of early 2019, Romero will be an artist in residence at the Institute of American Indian Arts, in Santa Fe, of which she is an alumna. Besides her work as a photographer, Romero directs the Indigeneity Program at Bioneers, a nonprofit organization based in Santa Fe dedicated to issues of climate change.

Above: Water Memory.

Above: Water Memory.

ROMERO WORKS AT UNDEREXPOSED STUDIOS, in Santa Fe. When I arrive, Water Memory is encased in a dense layer of bubble wrap, making the figures look more like shadows. I know exactly what it is, though; even muted, the color is unmistakable. It’s lying on its side awaiting shipment—someone just purchased one of the 10 editions—in a space she shares with three other photographers just off Cerrillos Road. The warehouse is spacious and minimal, with a loft and personal studios (“showrooms,” as Romero calls her own) for sitting with prospective customers. In hers, photographs cover every wall—large in scale, glossy, and picturing, for the most part, Native women. Many are friends or relatives.

Some look away from the camera, and others gaze right at it. The effect is a stare so dialed in, I’m hard-pressed to turn away. “That’s the beauty of working with friends and family. There’s a sense of trust. So they’re looking directly at me,” Romero says. In turn, the subjects look directly at viewers, at me. I return to them again and again, wondering whether each woman is privy to something I am not.

Just above a dusty-rose-colored couch hangs one such example, a massive photograph titled Sheridan (Reclining Chemehuevi Woman). This is Romero’s niece, who reclines on a craggy, white landscape, hair loose, chin slightly upturned, and eyes unwaveringly set forward. I look at her, and she looks back.

Native photography is, in many ways, about looking back—to histories of photography, film, and pop culture that have and continue to shape a national consciousness about who Native people are, how they dress, look, and act. Often deeply oversimplified, such perceptions stem from what the Sioux intellectual Vine Deloria Jr. called the “Edward Curtis Indian.” Curtis and others began taking photographs of tribes across the United States beginning in the 19th century. Those romantic—and staged—pictures have generated long-standing and damaging stereotypes that persist.

“My greater intention,” Romero says, “is to create a critical visibility for modern Natives, to get away from that one-story narrative, and to dig into our multiple identities. Our stories are entrenched in our ancestry and traditional ways of knowing, but how they manifest today, that’s what’s important to me.”

Romero’s The Last Indian Market, from 2015, playfully mocks and pays homage not only to Indian Market but to the city—Santa Fe—where much of that Curtisesque imagery gets recycled. Like its predecessor, da Vinci’s The Last Supper, The Last Indian Market depicts 12 “disciples”—Native artists and intellectuals wearing a spectrum of clothing, and a central figure, Choctaw artist Marcus Amerman’s “Buffalo Man,” an alter-ego-cum-performance-figure that he began playing in the 1990s. Buffalo Man is now thoroughly retired, his last performance recorded, fittingly, in The Last Indian Market. Wearing a white blazer, snout facing dead center, and a tuft of fur crowned by lopsided horns, Buffalo Man holds his hands outward, presiding over a table of horno bread. “It’s all so theatrical,” Romero says, half smiling.

“I’m the only one looking directly at the camera,” Amber-Dawn Bear Robe, from the Siksika Nation, in Alberta, Canada, says of her role, second to the left in the photograph. A photo historian and professor of art history at the Institute of American Indian Arts, Bear Robe says, “I was wearing a Renaissance-era Halloween costume and dentalium earrings to indigenize my outfit. It was like that for everyone. All of us brought our own personalities to the table.”

The storyline upends da Vinci’s configuration and its all-male cast of characters. At the same time, Romero blurs the lines between Western and non-Western traditions, replacing the solemnity of the original with comical irreverence. Much of the photography she stages is along similar lines. “Cara reframes stories from an indigenous perspective, which is going to offer an alternative history,” Bear Robe says. “For me it’s like a family portrait,” one that just happened to be taken in the empty interior of the Coyote Cafe.

To present that alternative history means reckoning with the legacy of Curtis and a host of others whose visual representations either totally excise Native people or exoticize them. It requires a new lexicon for picturing indigeneity, a pursuit Romero shares with contemporaries like Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie, KC Adams, Rosalie Favell, Shellie Nero, and Kali Spitzer, as well as previous generations of Native photographers, all of whom have emphasized that photography is no longer about being documented, but about self-representation.

“Cara’s building a narrative,” Bear Robe says. “She’s not hiding the fact that her photographs are staged. It’s hers, the one that she wants to create. And it’s an indigenous narrative we have not seen.”

Above: Oil Boom.

ROMERO WAS EXPERIMENTING with using a waterproof housing for her camera by taking photographs in Cochiti Lake when she realized the water was too murky to get a clear shot. What followed was a series of phone calls to every pool manager in Santa Fe, asking for a couple of days to snap photographs for her latest series, which involved being underwater. Nobody responded. Romero, who is warm and tenacious, didn’t take no for an answer. “I had a picture in my mind of how I wanted it to look, the color of the water and everything,” she says. “Finally, I just ended up renting a room at the El Rey motor lodge and making it happen. The managers definitely didn’t know what to think. It was very guerrilla.”

Her children held lights above the water to create the mysterious illumination, and a local scuba diver agreed to sit at the bottom of the pool at Romero’s side. He taught her the basics of scuba diving and, for the purposes of the photo shoot, how to breathe underwater with a tank. “I arrived and Cara was wearing a diving suit,” says Cannupa Hanska Luger, one of the Native participants she recruited for the picture. “When I saw Oil Boom later, I realized I’m in a sea of oil. I’m not me. I’m a placeholder for a story that is common to so many tribes.”

In Oil Boom, Romero transforms the water into oil through Photoshop. Hanska Luger’s arms are outstretched, his eyes closed, his body suspended in sepia brine. Along the horizon above his head, countless pump jacks for extracting oil loom, beasts in an industrial landscape. Hanska Luger, a social-practice artist based in Santa Fe, was raised on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation of North and South Dakota, which made news for much of 2016 for massive protests against the construction of the Keystone Pipeline. Their ancestral land was also flooded in the 1950s. Like other figures in Romero’s photography, he is a placeholder, or, better yet, a figure who is symbolic of a larger group or idea. He is himself and then more than himself.

TWO YEAR AFTER HER groundbreaking series of underwater photographs, Romero created Kaa (Clay Lady with Mesa Verde Design), a 50-by-44-inch print named after Kaa Folwell, a young potter from Santa Clara Pueblo. Folwell belongs to a long dynasty of women who have made pottery “just to survive,” she says. In this particular photo, Folwell personifies Clay Lady, a supernatural figure from Tewa oral histories. “One of the creation stories here in Santa Clara Pueblo,” Folwell says over blue corn atole at La Cocina in Española, “is that we’re all made from clay.”

In the photograph, Folwell is nude, her body completely covered in white clay, as geometric designs culled from Mesa Verde ceramics traverse the surface of her skin from the neck down. “Cara loved how the clay crinkled on my skin, so she kept lathering it onto my body,” Folwell says. Romero collected it from a site on the Chemehuevi Reservation, and bits of it are scattered across the white surface where Folwell kneels with one hand covering a breast. Her back arches and her hair fans out, as if she’s just snapped her head back. It’s a moment of extreme movement—emergence—stilled at one eight-thousandth of a second. “It creates that feeling of excitement, but it also visualizes Clay Lady’s temperamental nature and unpredictability,” Romero says. “It’s like that moment when you fire pottery—that moment of chemical reaction.”

“There’s such a lack of photographs of strong Native women,” Folwell says. “When you do an internet search, the same 30 photographs come up, and most are from Edward Curtis. So how do we look at Native women as human with all the emotions that come with that humanity, including being sexual? Cara doesn’t sexualize those she’s taking photographs of, but she does show that you have a flame inside.”

The question for Romero is “How can I make photographs that convey the power of Native women like never before?”

The answer is complex, not only because of the history of photography and other media, but also because Romero has to contend with an ongoing epidemic that has implications across the Americas: Indigenous women are murdered or go missing at far higher rates than any other group of women, which, for the most part, has gone unreported until very recently. “It’s something you always have to think about,” Folwell says—not exploiting Native women’s bodies either pictorially or otherwise.

In her studio, Romero points to Kaa, showing me how the arch in Folwell’s back could be read in different ways. But here, the way she captured her kneeling with her head thrown back was empowering rather than sexual. Out of the whole contact sheet, that nuance, along with the imperfect texture of the clay as it dried on Folwell’s face, determined which photograph Romero eventually chose. Women are drawn to these photographs, she tells me. They make up 95 percent of her customer base.

It’s important, Romero explains, that she sit with every one of her subjects before and after the shoot, to make sure they are comfortable with the dynamic on set and with the resulting photographs. Each project comes from a “maternal place,” she says, one that’s “not exploitative.”

“It was a conscious decision to make them as a counter to that narrative of oversexualized Native women,” she says. “For me, they beg the question ‘Are these women real or supernatural?’ Because we should feel supernatural—we have a lot of medicine, and this is exactly how we hold ourselves. These are our bodies. We are allowed to feel any way we want without being harmed, without being raped or murdered. And that’s why it’s powerful to have a woman behind the camera, and in editing: to celebrate our power.”

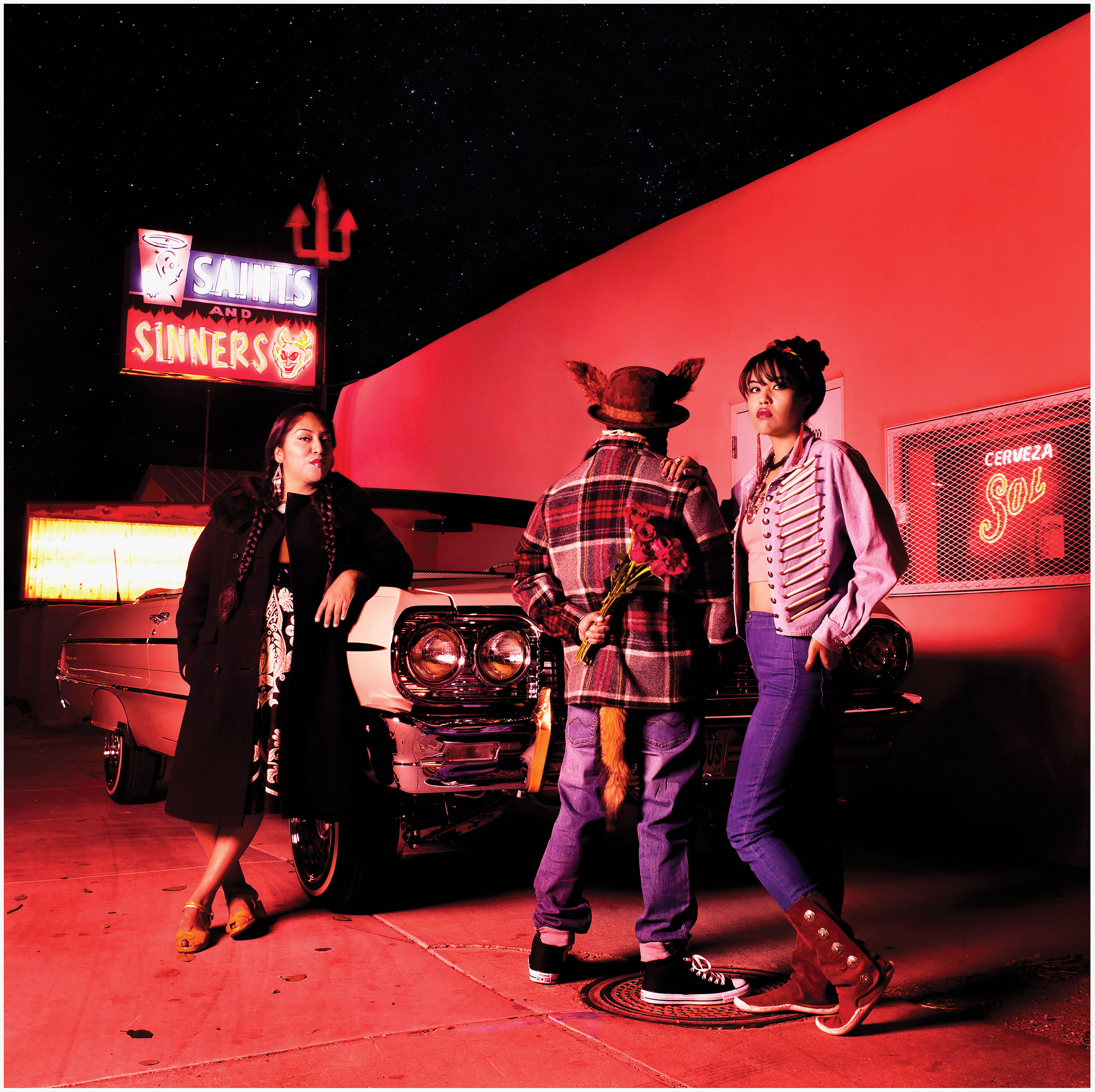

IN ROMERO'S MOST recent project, Coyote Tales No. 1 (featured in the December 2018 issue of National Geographic), Coyote, the trickster figure, stands with his back to the camera, holding a bouquet of roses, and the promise of shady dealings. Two women (Folwell and Dina Devore, of Kewa and Jemez Pueblos) stand on either side, in front of a gleaming white 1964 Impala. All are under a crimson glow. Folwell wears a jacket that once belonged to her auntie—Native couture from the 1970s—while Devore, Romero’s expert “ride or die” makeup artist and model, is decked out in vintage clothing and long braids. Derek No Sun Brown, of Shoshone Bannock and the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa, dons ears and a tail, his pants cuffed above a pair of slick black Chuck Taylors.

Above: Coyote Tales No. 1.

Above: Coyote Tales No. 1.

Saints and Sinners, a liquor store and bar in Española that’s been around since anyone can remember, is in the background. Its iconic sign looms above, red and white neon with an angel on one line and a devil on another, a campy echo of Coyote’s own unpredictability.

“When I first began thinking about Coyote Tales, I was like: You can’t put Natives in front of a liquor store,” Romero says. “But it became another examination, another problem-solving moment. That’s when Coyote came to me. He makes questionable decisions, but we still love him anyway. I’m 10 years sober, but I can still remember the excitement of my twenties, of dating, cruising, car culture, and places like Saints and Sinners. A lot of the pieces are autobiographical.”

While using Saints and Sinners as a backdrop might be frowned upon by some within and outside of Native communities, “it all began with the lowrider. I wanted to use an ‘Indian’ car,” Romero says, making air quotes around the word Indian, then laughing. After rolling up to a car show in Española, she convinced Fred Rael, of Prestigious Car Club, to lend his baby. He brought it in a trailer as she set up a blimp light, like a huge moon, in the parking lot. Her equipment spilled out on the road and passersby began honking. Others waved. Finally, a police officer stopped. “Everyone thought it was over or that we’d get arrested,” she says. Instead, he put orange cones around the scene, guiding traffic around their makeshift shoot.

Romero’s photo captures that ambiguous moment when nights begin and choices are made, for better or worse, the point where the scales tip toward the mischievous. Coyote tests and teases you, signifying just that juncture. And in that way, the air of the supernatural is palpable, underscored by the brilliance of the night sky. In Diné (Navajo) thought, so impatient was Coyote to have the stars in the sky, he threw them up there himself without order.

By the same token, reality grounds the image. “We don’t need poverty porn, but we can nod to our humanity,” Romero says of the shoot. “It really fed off that idea, what did the Pope say, ‘Who am I to judge?’”

Most of Romero’s photography shares that philosophy, the sense that the misconceptions of previous visual histories have no bearing on her own narratives.

“I walked away from that shoot feeling like it was a failure,” she says. “And then I realized the artwork made itself. It was just waiting for me to see it.”

PICTURE HER

As an artist in residence at the Institute of American Indian Arts from mid-January to early February, Romero will have a studio open to IAIA faculty, students, and the Santa Fe community (iaia.edu/artist-in-residence/artist-in-residence-artists).

Peters Projects, a gallery in Santa Fe (1011 Paseo de Peralta), represents Romero. She is featured in the exhibition Rising Tide: Twelve Women Artists, open through March 15, 2019.

Romero’s photography is on view by appointment only at Underexposed Studios.