A CAVERS’ MAP IS DOTTED WITH QUESTION MARKS, indicating where other cavers have spotted a crack or crevasse that offers a possible unexplored passage. Some become impassably small. Some dead-end in alcoves. Others open into ballrooms of crystalline features, mineral fingers that trace lines drawn by dripping water.

“Imagine a tunnel, and nobody has ever been there. You walk into this passage, and what’s around the next corner, nobody knows,” says Max Wisshak, a geoscientist, caver, and co-editor of Lechuguilla Cave: Discoveries in a Hidden Splendor. “Maybe you find something new that not only in this cave nobody has seen before, but in the entire world nobody has seen before.”

Those kinds of experiences are what motivated Wisshak to travel from his home in Germany and spend a week underground in New Mexico’s labyrinthine Lechuguilla Cave with a half-dozen near strangers, while following strict practices to protect a delicate, pristine environment from his own presence.

Explorers began to plumb the depths of Lechuguilla, the largest known cave in Carlsbad Caverns National Park, in 1986, half a century after the first mapping of the Big Room. So far, they have documented more than 150 miles of tangled, subterranean passages but have yet to find its limits.

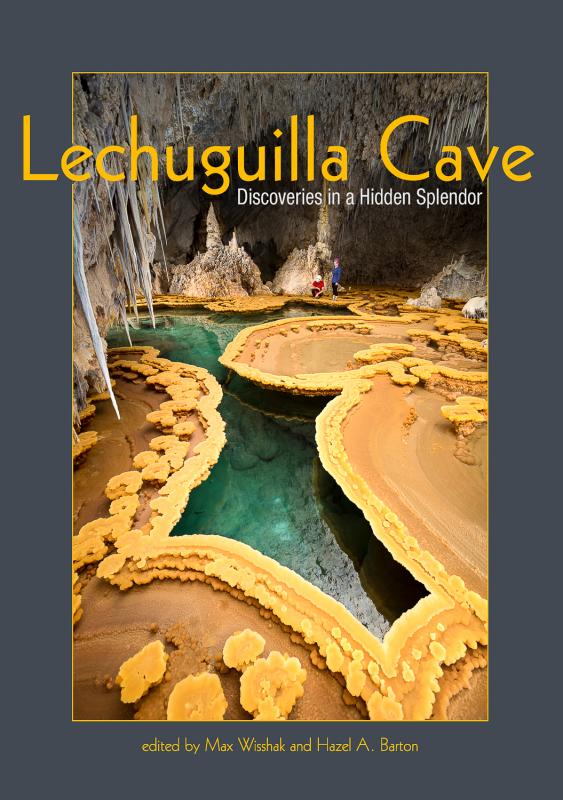

Park staff restricts access to a handful of research teams and explorers each year to preserve a rare opportunity for studying biological and geological processes away from human influence. Still particularly active, Lechuguilla continues to grow spectacular speleothems that add to existing wonders—gypsum chandeliers more than 18 feet long, lacy fingers of limestone taller than a person, curling spindles, crystal feathers, and pools rimmed with golden curlicues.

In 1994, Wisshak was driving through the Southwest’s national parks when he stopped at Carlsbad Caverns and picked up a book documenting the early years of Lechuguilla exploration. At the time, he was a college geology student and had only dreamed of exploring such a virgin place. But he began caving and received an invitation to Lechuguilla after meeting Hazel Barton, a University of Akron microbiologist and co-editor on his latest book, during a caving trip in New Zealand.

Wisshak made his first trip to Lechuguilla, rappelling into a cave 1,565 feet deep, in 2006. These expeditions require packing everything to live in the cave for eight or so days, plus research and photography equipment, ropes, and other gear to travel through the cave’s massive galleries and uneven floors to designated campsites more than a mile away.

Meticulous measures aim to keep human contamination, even on a microscopic level, out of the cave. Clothing and shoes are changed so dust from one area isn’t tracked into another. Water is collected from designated sources so that pristine pools are spared human influence.

These untouched spaces illuminate new corners of our world. Highly specialized bacteria live in the cave, feeding on elements in the rocks. Scientists are still identifying these “extremophiles” and studying how they live. Barton and researchers like her have discovered clues to better understanding antibiotic-resistant “superbugs” and providing insights into how life could survive on other planets. Mineral formations also archive our changing climate, with trace metals indicating the average outside temperature in a record that can span two million years.

EXPLORE MORE

Learn more about Lechuguilla Cave: Discoveries in a Hidden Splendor, at lechuguilla-cave.info.

Inside, “Lech” feels like the tropics, Wisshak says, with temperatures hovering around 60–75 degrees and close to 100 percent humidity. It also requires some mental toughness to deal with the dark, confined spaces and to orient yourself in a maze of tunnels.

White gypsum dominates the cave walls, so headlamp beams skitter off shiny, bright surfaces. “Many landscapes look like it’s winter and there’s frost on the ground,” says Wisshak, who has now taken more than a dozen trips into Lechuguilla.

Even with all the mysteries and discoveries underground, there’s something magical about climbing out again. “When we reach the entrance and the first sunrays hit us, that’s still a very special feeling for us every time,” Wisshak says. “It’s a combination of seeing the sun again, hearing the birds again, smelling the plants—and all that is combined with a big relief that the expedition was a success.”

DARK ROOM SECRETS

Follow these underground photo tips.

Never use the flash on your camera. “Direct flash is boring,” says Max Wisshak, co-author of Lechuguilla Cave: Discoveries in a Hidden Splendor. If possible, use a remote flash to light a feature from behind or the side to better convey the room’s dimensions and drama. Watch in the Big Room for some strategic lighting choices that help set up these effects.

Consider the feeling you’re trying to capture. Is the focus on a caver making a challenging move through the terrain? Will having a tiny person in a massive space better convey its scale? Or is this a portrait of an intriguing speleothem from which a person would only detract? “It’s kind of an art form where you need to compose the image in your head,” Wisshak says.

Take advantage of technology. Use your camera’s LED screen to check your work and tweak the scene and lighting. “It’s dark there,” Wisshak says. “You never see the caves like you see them in the picture later.”