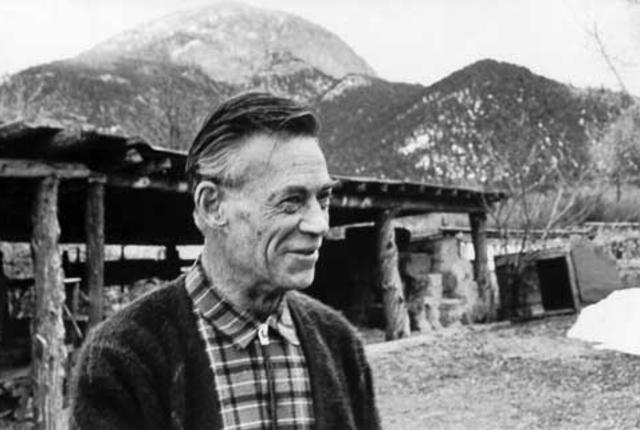

Photograph courtesy Barbara Waters.

The Man Who Killed the Deer: A Novel of Pueblo Indian Life (1942)

By Frank Waters

Considered Frank Waters' masterpiece—in a body of work that also includes Book of the Hopi, The Woman at Otowi Crossing, and Of Time and Change—The Man Who Killed the Deer is the story of a Taos Pueblo Indian haunted by the spirit of a deer he killed out of season and without ritual respect. This violation of both his tribe's and the white man's laws sets in motion events that ultimately lead to his redemption and the return of ancestral lands to the Pueblo. Because it generally raised public awareness of Native American life, and specifically the plight of Taos Pueblo, many credit this novel with helping facilitate the U.S. government's return of 48,000 acres, including its sacred Blue Lake, to the Pueblo in 1970.—P. W-B.

Death Comes for the Archbishop (1928)

By Willa Cather

Considered one of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century, Death Comes for the Archbishop follows the lives of two French-born Jesuit priests dispatched to the New Mexico Territory to reclaim the Roman Catholic Church from rogue priests who had been abusing both church tenets and the natives of the region. Rich with local legend and landscape, the novel—based on the life of Bishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy, who arrived in New Mexico in 1851—seamlessly blends fiction and fact as it explores faith, friendship, and loneliness on the Southwestern frontier.—Patricia West-Barker

Red Sky at Morning (1968)

By Richard Bradford

Red Sky at Morning is a classic American coming-of-age story often compared to Catcher in the Rye—although its sly humor and subtle exploration of social, racial, and religious prejudice are more reminiscent of Huck Finn than Holden Caulfield. Trading ham with Coca-Cola sauce for carnitas, the novel's 17-year-old, Alabama-born narrator learns about life, love, danger, honor, and responsibility while spending a year in a largely Hispanic New Mexico mountain town suggestive of Santa Fe in the 1940s.—P. W-B.

House Made of Dawn (1968)

By N. Scott Momaday

When, in 1969, N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa-Cherokee) became the first Native American author to win a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, for House Made of Dawn, many considered it a breakthrough for Native American literature. Based on events at New Mexico's Jemez Pueblo, the novel follows the journey of Abel, who is estranged from his culture by service in World War II and enters an Indian relocation program that sends him to Los Angeles. The opening song of the Nightway, a Navajo healing ceremony, gives the book its title and returns Abel to his native landscape—and the possibility of redemption.—P. W-B.

Bless Me, Ultima (1972)

By Rudolfo Anaya

This novel helped cement Chicano literature's bona fides, but was also controversial enough to be banned in some Colorado and California schools for its profanity and supposedly pagan content. This mystical classic has sold more than 300,000 copies and been filmed as a movie (still in post-production). Told from the perspective of a seven-year-old Hispanic boy who falls under the sway of his Aunt Ultima, a curandera (healer) in 1940s rural New Mexico, it's a mesmerizing journey into magic and spiritual forces. Think: Harry Potter transplanted among vaqueros (cowboys) and brujas (witches) in a secluded village on the New Mexican plains.—Wolf Schneider

Mayordomo (1988)

By Stanley Crawford

This nonfiction chronicle of an acequia in northern New Mexico is a perceptive observation of how the rhythms of nature affect farming life in Dixon, a rural Hispanic-Anglo village. It's filled with author Stanley Crawford's wry insights as he takes over the apportioning of ditch-water rights as mayordomo (overseer of the acequia), in this practice that has guided agriculture in New Mexico for centuries. His leadership style? He forgos the shotgun carried by a previous mayordomo, but he's ever willing to wield a chainsaw and shovel, and to persuade his neighbors to pitch in. Crawford finds the drama amid the alfalfa and muskrats, willows and beavers.—W. S.

Black Mesa Poems (1989)

By Jimmy Santiago Baca

Abandoned by his mother at age 2, poet Jimmy Santiago Baca survived years of homelessness and drug addiction before teaching himself to read and write—and discovering a passion for poetry—while incarcerated (a story recounted in his stirring memoir, A Place to Stand). Winner of more than a dozen literary prizes, Baca's body of work illuminates a segment of Northern New Mexico culture generally inaccessible to outsiders. Bound by blood, water, memory, and dreams, the loosely bound narratives of his standout work, Black Mesa Poems, bring to life Baca's friends, family, neighbors, and Albuquerque's South Valley.—P. W-B.

River of Traps (1990)

By William DeBuys and Alex Harris

The river is the Río de las Trampas, in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains; the village, El Valle; the life, that of Jacobo Romero—neighbor, friend, and teacher to the authors, who moved to the state in the 1970s. Romero wasn't a sentimental man, nor is this beautifully written book, which honors him and his vanishing lifestyle in an isolated mountain village on the frontier. A finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 1990, River of Traps captures, in words and pictures, the individual and collective history of a complex man, and the unique culture and land

that bred him.—P. W-B.

The Place Names of New Mexico (1996)

By Robert Julyan

A serious reference work leavened with heart and wit, this book traces the naming habits of the region's first settlers, the Spanish conquerors who arrived in the 16th century, and the Anglos who flooded the territory in the 19th century. By offering insight into more than 7,000 historical and geographic features, The Place Names of New Mexico creates what its author calls an "autobiography" of the state.—P. W-B.

Scrapbook of a Taos Hippie (2000)

By Iris Keltz

The definitive insider account of '60s hippie culture in Taos, this lively social-history memoir brims with interviews, newspaper clippings, and groovy photos. It conveys the idealistic spirit of the times as embodied by acid cowboys from communes like Reality Construction Company, and hippie homesteaders dropping out to embrace woodstoves and kerosene lamps. You can find other intriguing books about the legendary communes of Taos and environs—like Huerfano and New Buffalo—but Keltz masterfully assembles all the essential facts and characters here (and even postscripts their lives in 2000).—W. S.