Above: Scenes from the citizenship ceremony at Aztec Ruins National Monument. Photographs by Jeremy Wade Shockley.

We have come many miles to this place where so many have come before.

The event that drew us from different places by way of different roads won’t start for a while, so we wander, scattered, among the stacked-stone remains of a Puebloan community that arose in 1100, only to be abandoned by 1300. But all paths at Aztec Ruins National Monument lead to the Great Kiva, and it’s there that everyone gathers—nine people ready to become full-fledged Americans, along with families, friends, and strangers, who line the walls of this underground auditorium. All of us await the start of a naturalization ceremony that holds an echo of ancestral gatherings intended to strengthen a community’s bonds among members new and old.

“This whole site is a sacred place for Pueblo people,” Nathan Hatfield tells the group, “and the Great Kiva might be considered the most sacred place on this piece of land.” A park ranger for both Aztec Ruins and Chaco Culture National Historical Park, Hatfield leads interpretive programs at both sites and sees parallels between what once happened here and what will happen today.

“This was always a gathering place,” he says. “We know people traveled from far and wide to get here. I like to think one reason they came was to celebrate the unification of different clans or parts of the culture. This ceremony is our way of welcoming you into our clan. We’re carrying on a tradition from hundreds of years past.”

Every year in this nation, one million people from all over the world become naturalized U.S. citizens. About 2,800 of them live in the Citizenship and Immigration Services district that runs from Truth or Consequences north to the Colorado state line. To qualify, they must have been legal residents for five years—three if they’re married to a U.S. citizen, or even less if they volunteer for military service. In an interview with a citizenship officer, they must demonstrate a reasonable command of English, correctly answer 10 civics questions, assert that they are of good moral character, and promise to abide by the U.S. Constitution.

Many choose to take their oaths in massive ceremonies at places like the Albuquerque Convention Center. But a few lucky others will be granted an opportunity to gather in smaller places with deeper cultural significance. National Park Service sites have become especially popular in recent years, including Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument, Fort Union National Monument, El Malpais National Monument, and Petroglyph National Monument. Bandelier National Monument holds its ceremony every Fourth of July.

At the October event in Aztec Ruins, the soon-to-be-citizens represented the countries of Mexico, Iraq, Iran, Vietnam, and the Philippines. They sat in folding chairs near a long-cold firepit that once burned throughout Puebloan ceremonies. The smoke would have risen up the two-stories-tall structure to a roof opening now covered in glass. A color guard made up of JROTC students from Aztec High School carried the flags down the stairs. Amber Swenk, a local performer, sang the national anthem as people in suits, ties, and hijabs, some of them soothing restless children, looked on.

Read more: For Ancestral Puebloans, Chaco Canyon was the center of the world.

For those who are born into U.S. citizenship, events such as these serve as a reminder of the precious gift that was given, and of all that we stand to lose. Among the participants, you can sense the mixture of nerves, pride, and joy. They fidget with their programs and try to memorize the oath ahead of time. Their relatives aim cameras at them. They stick around for cookies and tea. Often, the local League of Women Voters sets up a registration table to kick-start their newly obtained voting rights. Speakers encourage them to blend their traditions with local ones and urge them not only to vote, but to talk with their elected officials, to support military troops, to play active roles in their communities—reminders of how every citizen, native or naturalized, can measure their own commitment.

Citizenship events are open to the public. After the introductory speeches, when the applicants finally stand and raise their right hands to repeat the oath, even onlookers get choked up. The oath itself is densely worded, and it carries tough demands: renounce your birth country, including “potentates,” and vow to take up arms to protect America. But to those who traveled far from all they once knew—who built new lives, who came together, and who now seek the promises of this country, of this clan—it’s worth the journey.

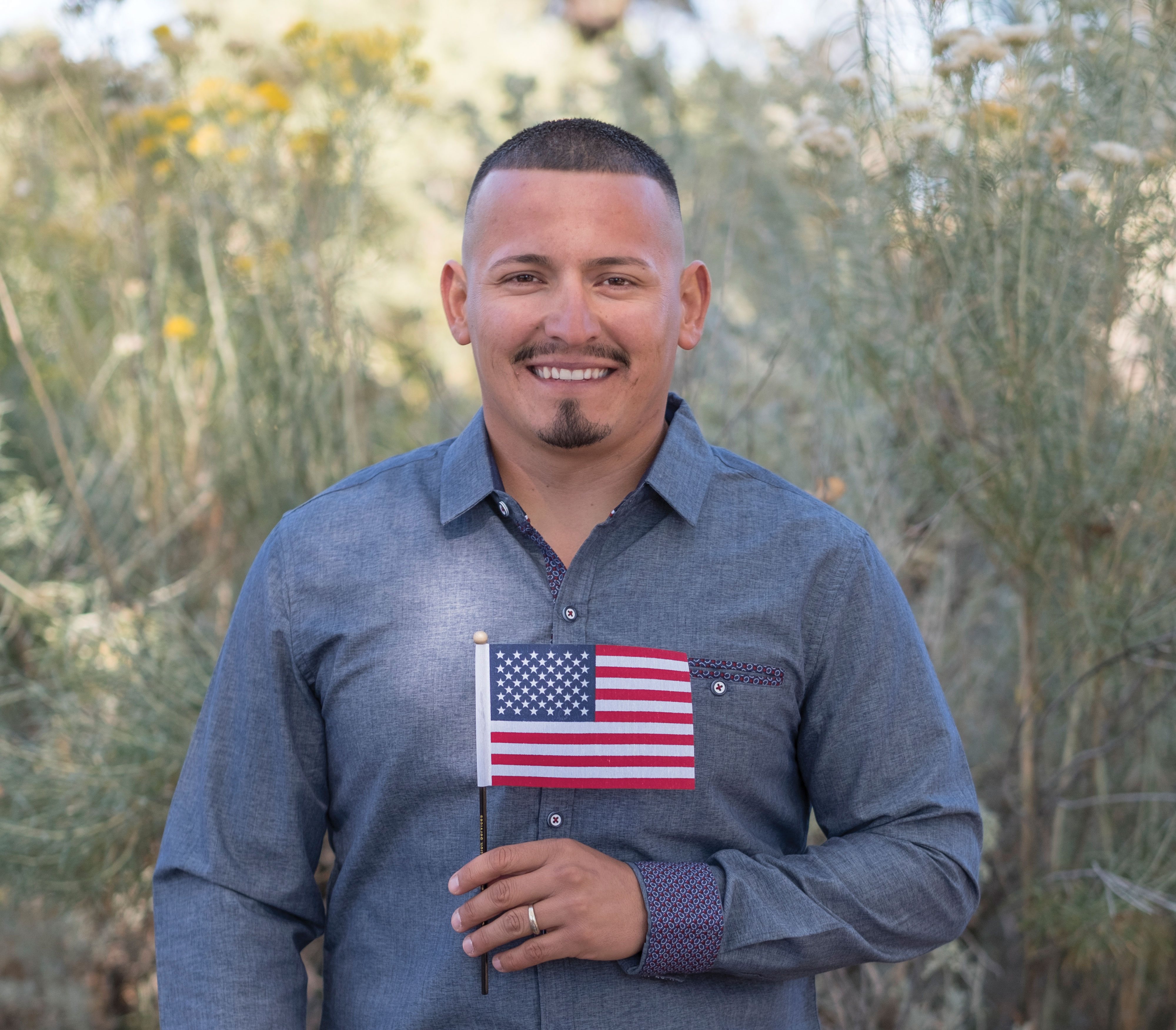

Above: Jesús Castillo.

Jesús Castillo

Mexico

“It was something special—blessed,” to take the oath inside the Great Kiva, Jesús Castillo says after the ceremony. An oil-field pipeline worker in Farmington, he came from Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, in Mexico, with his family when he was just 12 years old. Now grown and with a family of his own, he says, “I want to be part of America and vote in the federal election.”

Jhay Luevano

Mexico

A chance to move into a management role at Sam’s Club drew Jhay Luevano (above, in light blue shirt) to Albuquerque from Lubbock, Texas, last year. His family had moved to Texas in 2008 from their home in Aguascalientes, Mexico, when he was but a teen. “I feel like all my life I’ve been here and that my future is here. “I didn’t feel I could make a future in my home country. The opportunities here are limitless.” He also found a welcoming melting pot, often typified by what lands on his plate. “I like all kinds of food, just like I like all kinds of cultures,” he says. “There’s a guy from El Salvador who brings pupusas to work and shares them. That’s what I like about the U.S.: You get all of it at once.”

Above: Houmam Moussa, originally from Iraq.

Above: Houmam Moussa, originally from Iraq.

Javier Segovia

Mexico

For 25 years, Javier Segovia has driven commercial rigs in the United States. A native of Rodeo, Durango, in Mexico, he lives in Farmington, where he’s driven for a nursery, delivering plants, and for Waste Management, carrying away trash. He was married to an American and helped raise her children, along with two of their own, but that wasn’t enough. “I want to be a full American, to have the feeling of being a real American,” he says. He has a new wife and child back in Mexico and hopes to bring them north as well and introduce them to a state that once was part of the Mexican Republic. “Here in New Mexico, you can feel the Mexican culture in many ways. New Mexico holds that culture for us. New Mexico made me feel like I was home, and the benefits of being here are what we all wish for and hope for: the freedom. Back home, we had a lack of freedom and opportunity. This is the country for me.”

Above: Phoebe Carlson.

Above: Phoebe Carlson.

Phoebe Carlson

The Philippines

Nearly 16 years ago, Filipina Phoebe Carlson and her husband, Dennis, met on an online dating site and soon became inseparable. “New Mexico was the first state I got to fall in love with,” she says. “Over the years, he would say, ‘We’re going to meet in New Mexico.’ I’d say, ‘Okay!’” Eventually they married, and she began following him to his jobs as a geotechnical engineer, including a stint in Australia. On their return, they decided to spend a few days in New Zealand. Still holding a Philippines passport, Phoebe was barred from leaving the airport. “That’s another reason I want U.S. citizenship,” she says. “Dennis travels a lot. Wherever he goes, I can go.”

For a while, they lived in Los Alamos, where she became a fan of downhill skiing and of the over-the-top Smith’s grocery store there. The couple now lives in Fruitland, near Farmington. She’s developed a hankering for chiles rellenos, but mostly for the people she found here. “They’re so friendly. New Mexico is so family-oriented. People open doors for you here.”

Every January, Carlson draws on her roots in Cebu City, where the Sinulog–Santo Niño Festival turns into a Filipino version of Carnival. She re-creates her own version of the ceremony in New Mexico by making special foods and inviting friends to the party. “Magellan landed in Cebu,” she explains, “and gave them a statue of baby Jesus. We believe it’s a miracle. It heals everyone who’s sick. Every January we celebrate it. It’s like a dance we offer to the young Jesus.”

Alex Ibarra

Mexico

Just four years old when his family moved to Albuquerque from Culiacán, Sinaloa, in Mexico, Alex Ibarra (right) has found his calling as a husband, a father to three young girls, and a carpenter. “I just really like being in the shop and building with wood,” he says. New Mexico appeals to him, he says, for its weather, people, food, and proximity to Mexico, where most of his family still lives. “We have big get-togethers for birthdays and things like that,” he says. “I’ll eat anything, as long as it has chile—enchiladas, tacos, but also shrimps and seafood, because we come from a coastal region.” He’s wanted to become a U.S. citizen for a long time, he says, “because I know I’m going to stay here. I think I contribute a lot to this country. We came for a better life, a better economic situation. I want to vote. I want to stay here.”

Above: Ruby Ta, originally from Vietnam.

Above: Ruby Ta, originally from Vietnam.

Alice Jackie Puccetti

Field Office Director

“I know the journey has been long, and some of us thought this day would never arrive,” says Alice Jackie Puccetti, field office director for the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, before administering the oath. “I’m sure you already feel like Americans in your heart, but today you become Americans on paper, too.”

OATH OF ALLEGIANCE

This oath is recited at every citizenship ceremony.

I hereby declare, on oath, that I absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, of whom or which I have heretofore been a subject or citizen; that I will support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I will bear arms on behalf of the United States when required by the law; that I will perform noncombatant service in the Armed Forces of the United States when required by the law; that I will perform work of national importance under civilian direction when required by the law; and that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; so help me God.