FIRST THE OIL PUMP BROKE, then the semi’s electronic control unit killed the engine, and now Frank Felty and Ronald Woodruff are stuck in Clines Corners. They don’t yet know that they just joined a legion of other people in the broke-down-in-Clines-Corners club, a select group whose tales of woe haunt the arrays of John Wayne shot glasses, shelves of glitter globes, pillars covered with Route 66 magnets, and a couple of taxidermy jackalopes. A few more hours of drizzle will fall upon the high and otherwise barren plains before a tow truck can drag their rig to Albuquerque, 60 miles west.

Felty pushes around the last of his Subway breakfast on a paper plate and shrugs. “I’ve been driving for a lifetime. What makes a great place to stop is food and coffee. That about does it. Plus the restrooms. This is a good one. We’ll pass the next few hours eating and drinking, walking around, looking at all the jewelry. After a while we’ll say, ‘Oh, my daughter would like this necklace.’”

With that, he sums up all that elevates this outpost in the near middle of New Mexico into a gotta-stop cabinet of curiosities. It’s a service station, convenience store, restaurant, curio shop, fudge shop, candy shop, rock shop, jewelry shop, post office, RV park, and surprisingly good place to score Ariat boots and Pendleton purses—with the bonus of clean restrooms and a Zoltar fortune-telling machine. Miles before you arrive at the intersection of US 285 and I-40, a fusillade of billboards bullet-point the many delights it can deliver. SPOONS. THIMBLES. ICE. CHILE. KEYCHAINS.

Wait—people need thimbles?

No! Let’s stop anyway.

Read more: Finding respite—plus chickens and puppies—at Santa Fe’s Sunrise Springs Resort.

Starting in May, Clines Corners will premiere even more attractions. A full-service truck stop with a laundromat, showers, and five acres of overnight parking. Package liquor sales starring New Mexico craft beers and spirits. La Cocina, a 6 a.m.–to–10 p.m. restaurant serving enchiladas and margaritas. Fireworks, fireworks, fireworks.

As first a pioneer and now a vestige of the overblown roadside stops that once lined old Route 66 (“Live rattlesnakes!” “Stagecoach rides!”), Clines Corners has served nearly every need of the motoring public since 1934. Through four owners, countless snowstorms, and an eternity of broken-down-in-Clines-Corners stories, it stands as a fortress of goodness, unifying the lowbrow with the gourmet, the biker with the sophisticate, and me with a dizzying choice of miniature personalized license plates. I’m leaning toward REBEL when General Manager Jeff Anderson approaches me so fast he’s almost a blur, braking on his way to a ceiling reconstruction crisis, part of the truck-stop project.

“The whole concept here,” he says, “is people stop to use the bathroom, and we get them to spend $20 on rubber snakes and tomahawks. And it works. In no marketing book does it say, ‘Get them to stop for the bathroom and they’ll spend $20,’ but they do. And if they’re hungry, they’ll eat.”

Outside Clines Corners Travel Center.

Outside Clines Corners Travel Center.

ROY “POPS” CLINE WAS, AT BEST, AN opportunistic entrepreneur. That’s according to his grandson George Everage, a retired Albuquerque accountant, who loved hearing his parents and grandparents wax on about the olden days and can still reel off their tales. From the 1910s through the 1920s, Cline, his wife, their son, and six comely daughters flitted from Oklahoma to Rutherton, near Tierra Amarilla, where Pops ran a post office plus a nickel theater in a tent before freezing winters persuaded them to head south. He traded the post office for a chicken farm that turned out to have a dugout for a home, so he traded that for a hotel in Buford, which hadn’t yet transformed into Moriarty.

The girls were a great workforce, and soon Pops could pay for a bunch of acreage out where old Highway 6 crossed Highway 2—“highway” being, in those days, a relative term. Highway 6 was little more than a dirt road bulldozed across the state’s beltline. Through Tijeras Canyon, it looked more like a cow path. By 1926, westbound motorists could take the paved Route 66 north out of Santa Rosa, loop through Santa Fe, and drop down to Albuquerque. But drivers looking at maps likely thought Highway 6 would be the faster route and chose it. Pops opened not one but two service stations, a Standard and a Conoco, set across the way from each other to catch them coming or going.

On the rare occasions when the bulldozed route changed, he moved his makeshift stations. And when a political tussle in Santa Fe resulted in a complete realignment of Route 66 straight through his acreage, Pops hit the goldmine. He built a neat white box of a store emblazoned with his name: Cline’s (with, yes, an apostrophe). He served 15-cent bowls of chili that drew people from miles away. And he made more profit fixing flats than filling tanks, roads being what they were.

From 1938 to 1940, he and the family weathered some of the worst blizzards the state has ever seen. Perched above 7,000 feet, with nothing but barbed-wire fences to buffer the blasts, Clines Corners (without the apostrophe, as the maps came to call it) has always suffered Mother Nature’s contrary side. Everage flips past picture after picture of snowdrifts so high they threatened to topple the outhouse. “And when the snow melts,” he says, “the soil out there is nothing but caliche that turns into clay. Everybody would get stuck.”

Owner George Cook with son Nicholas, who's learning the family business.

Owner George Cook with son Nicholas, who's learning the family business.

Eventually Pops sold the operation to a couple of state policemen and hauled the family to Kingman, Arizona, where he opened a similar enterprise near Hoover Dam. It went great until World War II erupted and all the nation’s gasoline, food, and labor turned to the war effort. Then Pops brought the family to Vaughn (“He bounced,” Everage says of the man’s admirable rebound percentage), where he ran the Doxie Hotel and made the most money of his life, selling plates of food and bottles of whiskey to fellows heading out on the troop trains that rolled through every day.

In the 1950s, Pops opened Flying Cline Ranch, a competitor to his original store, about 19 miles east on Route 66, changing the name to Flying C after the new owners of Clines Corners threatened to sue him. Everage’s father, also named George, had married the prettiest of the Cline girls, Mae Lucille, and sometimes helped at Flying C, which had 48 employees each summer, served lunches to 22 busloads of people a day, and illegally kept five slot machines that covered every penny of the overhead. Little George got a good look at the roadside stops then lining Route 66. “Between Clines Corners and Santa Rosa, there were 25 to 30 of these mom-and-pop places,” he says. “One would have a zoo in the most terrible conditions. One had a bear. Every place had one or two emaciated rattlesnakes.”

By then the Clines Corners cops had parted ways, one of them opening yet another Route 66 enterprise, the Longhorn Ranch, a faux Western town in Moriarty with stagecoaches, Indian dances, and “a museum with antique firearms and two-headed calves,” Everage says.

Once airplane travel became safer and more affordable, the roadside stops dried up. Remnants of the Longhorn Ranch sign are visible, but not much else. With the advent of interstates and a business shift away from freighting goods on the railroad in favor of using big rigs, the few survivors grew into sprawling truck plazas, now mostly owned by national conglomerates like Love’s, Flying J, and Travel Centers of America.

Clines Corners persisted, still local and still the only business for miles and miles around, all 40,000 square feet of it standing as a beacon of human interest and corporeal relief amid lonely, rolling ranchland.

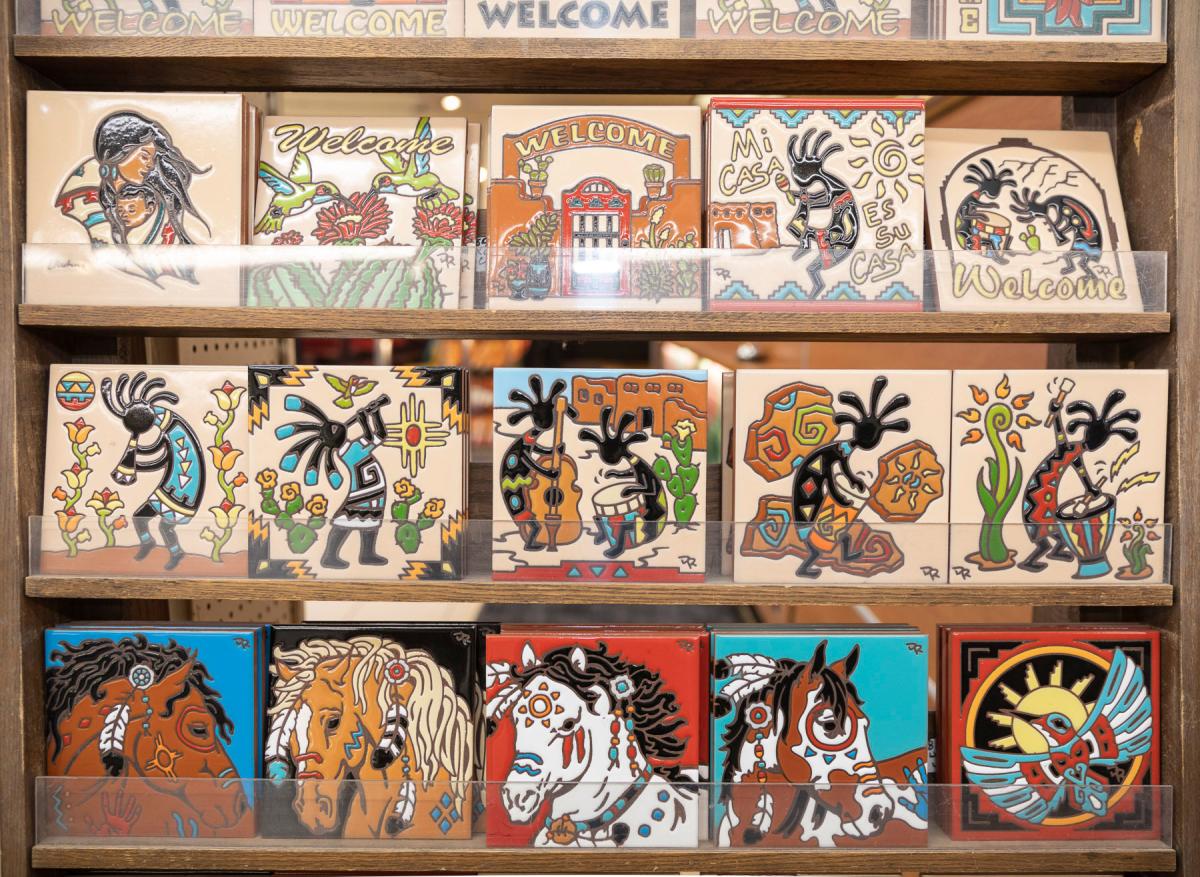

Tchotchkes and food attract customers 24 hours a day.

Tchotchkes and food attract customers 24 hours a day.

“THERE'S SOME OLD SAYINGS IN THE BUSINESS,” says current owner George Cook. “One of the most important is ‘Buy the merchandise right.’ That means volume buying. I’m the biggest buyer of souvenir merchandise in New Mexico.”

Besides Clines Corners, Cook owns the Covered Wagon, a rambling tourist mecca on the Old Town Plaza, in Albuquerque. He’s had the Sundancer Trading Company and Thunderbird Curio shops at the Albuquerque Sunport for 32 years and operates three joints near his family’s homestead: Taos Trading, Taos Cowboy, and Taos Mercantile.

“I used to come out here when I was a kid,” he says while taking a break in a vinyl booth at Clines Corners’ Subway shop. “My dad had a jewelry display here. I got to know everybody. I saw the opportunity.”

Today he owns 1,500 acres, much of it frontage along I-40 and US 285, enabling him to pepper the area with his Burma Shave–like billboards. “Only advertising I need,” he says. He offers employees enough trailer-park housing to handle up to 30 families, which sweetens the deal for the ones who slog through the overnight shifts or get stuck there during occasional snowstorms.

Stephanie Urioste, who helps Anderson, the general manager, with Clines Corners’ day-to-day affairs, has seen her share of the latter. “If they shut the interstate, those workers and travelers who are here stay here,” she says. “We open the restaurant, there are people everywhere, trucks everywhere. It’s chaotic.”

But last year, she recalls, when morning dawned after a monster snowstorm, one of those stranded folks, a stranger to all, grabbed a shovel and got to work digging out motorist after motorist. “Sometimes a random person, you don’t know what they’re going to do,” she says.

A selection of Native pottery.

A selection of Native pottery.

The lion’s share of the clientele comes from Texas, especially during winter. They turn north after stocking up and head to the ski areas in Santa Fe, Taos, and Colorado. Come summer, people from all over the world pack into the aisles, and with so many customers, you may not notice there’s a colossal buffalo head on one side of a pillar. On the other, bullwhips.

Because you never know what you might need on the road. Forgot to bring a dog dish? The convenience store can fix you up and provide collars and leashes, along with blue tarps, bungee cords, and a jack. There’s a $695 amethyst geode around the corner from some old lava lamps, near a display of novelty boxer shorts with high-larious sayings like BEWARE OF NATURAL GAS.

Sheila Foot commands the fudge counter, which for decades has sated sugar addicts with flavors like the perennial favorite, pecan praline. “I have a lot of repeat customers,” she says. “One comes in every six months and buys two full slabs of lemon meringue pie fudge. And I make it just for him. He calls ahead. He comes twice a year from Arizona, because he has property in New York. He buys other things, too.”

You can choose from bulk containers of saltwater taffy, mini Bit-O-Honey bars, Jelly Bellys, Lemonheads, and jawbreakers. T-shirts outsell everything, although the horno-shaped incense burners with cones of cedar, piñon, and juniper run a strong second. Pieces of “Genuine Native Made” Navajo and Zuni jewelry sit atop dried black beans in vitrine cases at the back. Cook buys it all from a dealer in Gallup. It’s mass-produced, though pretty enough, and satisfies those tourists who’ve been told they simply have to come back with something shiny.

“There is no better business than the tourist trade,” Cook says. “People are out to have fun. They want to learn stuff. You deal with people who are happy.”

Keeping Clines Corners running is more than a family affair.

Keeping Clines Corners running is more than a family affair.

Indeed, just as I’m about to abandon my own skepticism about the merits of purchasing a coonskin cap that doesn’t even fit, I spy a $140 full-length, buttery-soft leather apron on the wall and catch myself thinking, That’d make a great birthday present for my brother. I know I could grab enough silly junk to fill my grandnieces’ Christmas stockings, pick up a chile-print onesie for the baby shower next month, buy a birthday card for the friend I forgot, and even mail it from here. Phil Collins is crooning over the sound system, and he makes me wonder if maybe I, too, have been waiting for this moment for alla my life. Other than the inflated gas prices (they sell two million gallons a year, a tally sure to rise with the truck-stop pumps), could this actually be the best place on earth?

And that’s when the bad thing happens.

I notice Cook surrounded by staffers over near the candy shop. His arms are jabbing at the part of the ceiling that workers haven’t started on yet. I pull closer and gather that he doesn’t appreciate all the dust filtering down on his volume merchandise, shaken loose by the banging around. “Shut it down,” he says, and he doesn’t mean the new piping for the fire-suppression system.

He means the gift shop.

Read more: Pack your camera—and a sleeping bag. Deming’s night skies are calling.

Like an army of ants, workers begin pulling merchandise into storage, packing T-shirts into the candy area—which will stay open, along with the convenience store—and prepping the space to be curtained off, with only a hallway open from the restrooms to the Subway shop. “For how long?” I ask, my eyes as round as the saucers on the UFO-themed T-shirts. “Sixty days,” Cook answers, his words a thudding mallet on my heart.

We’re in the gray grip of January. I do the math. Late March before it reopens. For a business that serves largely as a way station, a pass-through point, the place where nobody knows your name but maybe you can find it printed on the side of a $5 pocketknife to prove that you were here, the interval feels like an unholy pause in the continuum. I teeter on the edge of an existential crisis, hearing from somewhere in my past a line from Waiting for Godot.

We always find something, eh Didi, to give us the impression we exist?

Stephanie Urioste whips up a batch of Cline Corner's fudge.

Stephanie Urioste whips up a batch of Cline Corner's fudge.

I resolve to find such meaning before it’s all closed off and march to the fudge counter for not one but two boxes of their best stuff. I turn to Zoltar, who has pestered me all day. Every time I approach the women’s room, he barks, “Vott are you vaiting for?” Finally I press a dollar bill into the slot, and he lurches to life, flapping his mannequin arms and speaking in a culturally inappropriate accent so painful that I don’t catch the words, and then he fails to spit out a written fortune.

My fate uncertain, I leave. The sun sets in a slurry sky, and as I drive away, three billboards wink me home.

CLINES CORNERS / THANK YOU.

CLINES CORNERS / COME BACK SOON.

CLINES CORNERS / TRAVEL SAFELY.