Editor's note: This essay was originally published in the March 1998 issue of New Mexico Magazine.

I’LL WAGER I LIVE OUT WEST because of clouds. Truly, my heart leaps up when I behold. There’s a billion miles of Big Wide Open to gambol in that never feels cluttered. Even when this vast dominating space is blank, I feel it’s just one grumble shy from rarin’ to go. The sky will explode at any minute. Up here in Taos that tension is endemic.

At times, I lead a chaotic life, full of theater and emotion. The air over this valley properly reflects my diatribes. But what can a writer like me say about clouds that isn’t a hackneyed stereotype, or reminiscent of the lyrical words on a best-selling record by Judy Collins? Not much. They’re fluffy and fleecy, big and booming, utterly diaphanous, charmingly puffy—

Excuse me, but um gee—y’know? It’s like calling dogs Spot and Fido and Rover, cows Bossy, and cats Puss Puss or Garfield. Doesn’t matter, though, does it? Let’s exempt atmospheric verities from a demand for original rhetoric. So: Each day, each hour, clouds reinvent the sky, serene as silk, big as hippos, loud as choo-choo trains. Their Greatest Show On Earth can create a brand-new postcard shot faster than I can whistle for help backwards.

Clouds frighten, then enlighten.

They kill people with lightning and floods and freezing shadows in January. They also soothe my soul, causing me to catch my breath and think of J.M.W Toner or Georgia O’Keeffe or Maxfield Parrish. They make me want to lie in a hammock and float indulgently, more lazy than a dandelion, more placid than a sheep.

I climb Tres Orejas Mountain in the middle of our sagebrush plain. There’s a rock shaped like a half shell on top of the southernmost peak. There lie I, a humanoid embryo curled into a basalt egg, staring straight up past the drifting buzzards toward some vast Theory of Relativity, azure-colored and without a single bit of vapor marring its “perfection.”

Has to be pretty windy up there, however. For suddenly a blink of white appears out of nowhere, and like a magician’s handkerchief, that raggedy cloud unfolds in size a dozen times over in the shake of an icy invisible wrist. Whoa, boy! Check out that albino blast of vapor growing so huge in shape it ultimately casts a shadow that actually makes me shiver. Then just as abruptly it evaporates, sucked back into a bright blue hole with hardly a protesting quiver: poof.

For years I have photographed clouds in all their splendor, bombarded by sunshine, glorious or inane. They are always eagerly willing—like enormous slavering puppies forged of cotton candy—to cater to my sense of melodrama.

“Money in the bank!” the mercenary moi cries gleefully every time those big vapor bozos go bonkers in cliché spasms almost too rococo to record on Kodachrome. And I reach for my camera, pointing the lens at heaven.

Weather. We all spend our lives schmoozing about the weather. We look up, we frown, we calculate the cabanuelas. It’s gonna rain, gonna be a hard blow, an early winter, a gosh darn drouth. I suppose everybody loves sunny skies except ME. Sorry, but I hate a dawdling along underneath a bland canopy. I want my firmament puckered by enormous cirrus feathers. Better yet, give me a heap of scary thunderheads looming up like Pittsburgh’s Steel Curtain or the Dallas Doomsday Defense. Frankly, I grow mega-excited when the sky starts lookin’ for a fight.

Yo, I’m game, bro—toss everything you got at me. Rain, thunder, lightning, cauliflowers the size of Norway, swollen cumulous giants, cumulonimbus abuelitos or La Llorona aching for a rumble, nimbostrati going ape, crystal smudges changing effortlessly into atomic columns—oh I do love a parade, Mame!

Sky and cloud, what’s not to adore and worship and gawk at? Massive and dark and bright and powerful: you can’t say a mysterious greater power isn’t trying. Or if that isn’t your cup of tea, how about Gerard Manley Hopkins?

…up above, what wind-walks!

what lovely behavior

Of silk-sack clouds! Has wilder, willful-fwavier

Meal-drift molded ever and melted

across skies?

Fair enough? I hope so. If you’re a Spanish speaker you might reply,

“Oralé, Geraldo—Tu y las nubes me traen muy loco.”

Or Native American?—“Lovely! See the cloud, the cloud appear! Lovely! See the rain, the rain draw near!”

Well, I have often declared: “Give me this day my daily cloud.. and I’ll not have need of wine.”

Now there’s a promise as true as wind and sky and provocative nebulosity.

And that’s the way it is from my perspective, aquí en Taos.

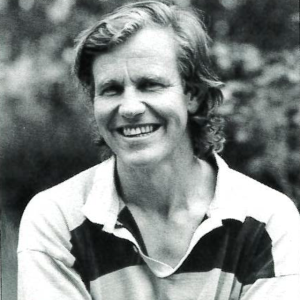

Born and raised in New York, he wrote his first novels there after college in the 1960s—The Sterile Cuckoo (1965) and The Wizard of Loneliness (1966)—and started a family. But Nichols fell in love with New Mexico after running away here for a week as a teenager, and he’d always intended to make it his home. He moved to Taos in 1969 and set about knowing it—the intimacies of its trails and streams, the interdependence of its peoples and cultures, and the complexity of its local politics.