Above: Author Stacia Spragg-Braude chronicles life and death, community and family in the village of Corrales. Photographs by Stacia Spragg-Braude.

IT'S A SUNDAY MORNING and I’m sprawled out facedown in the cemetery, trying to dig a grave by hand. The dawn sun, more golden now with the coming of autumn, is just cresting over the Sandía Mountains and spilling out into a bowl of blue. The land below me doesn’t boast the plush green of my Midwestern youth. This is like digging inside an hourglass, sand and time collapsing around you, except when you stub against an impenetrable ribbon of clay unraveling across the centuries-old riverbed, and you go nowhere. I’m almost two feet down when a couple of my Navajo friends, Sharon and Al, from Arizona, show up, shouldering shovels. Good friends help you dig graves.

One of the first times I strolled through Corrales’ San Ysidro cemetery was with my mom. She was visiting me from our home back in Indiana. I was in New Mexico for a six-month newspaper internship. We fell in love with the whitewashed wooden crosses that someone had made for all the lost and forgotten graves, the various Virgins of Guadalupe, the gardens of plastic flowers, the WE LOVE YOU JIM immortalized in a hand-drawn scrawl on Jim’s gravestone before the concrete had set up.

I was working at The Albuquerque Tribune and lived in town. I had found a tiny apartment that came with its own couch and a parking spot out front. The internship was to be a point between Here and There. Time to build a portfolio, have a New Mexico adventure, then head back out into the world. One day I visited a friend who lived in an apple orchard in a place called Corrales, just outside of town across the river. I liked how I felt when I stood among the trees. A place nearby was for rent, and I soon moved into an old adobe house that used to be the fruit stand. The floors slanted in such a way that you climbed a little uphill to get to the kitchen. The water had that unique rotten-egg smell that means it came from a shallow well by a river. Sometimes, when getting home late from a shift, I had to wait for a skunk to pass by before I could make a run for the back door.

Like so many others, I woke up one day living in a place a world away from where I grew up. Now it has been 25 years in this village along the Río Grande, under the mesa, on the edge and yet a world away from Albuquerque’s urban reach. Home has become stars in the sky I always knew to be there but couldn’t really make out before. I didn’t grow up in a semi-rural community, never before helped a colicky horse at midnight, or hoed rows of chile, or tried to round up a family of raccoons that had snuck through the dog door and settled in the laundry room to munch away on cat food. There was no reason why I would be pulled to this place.

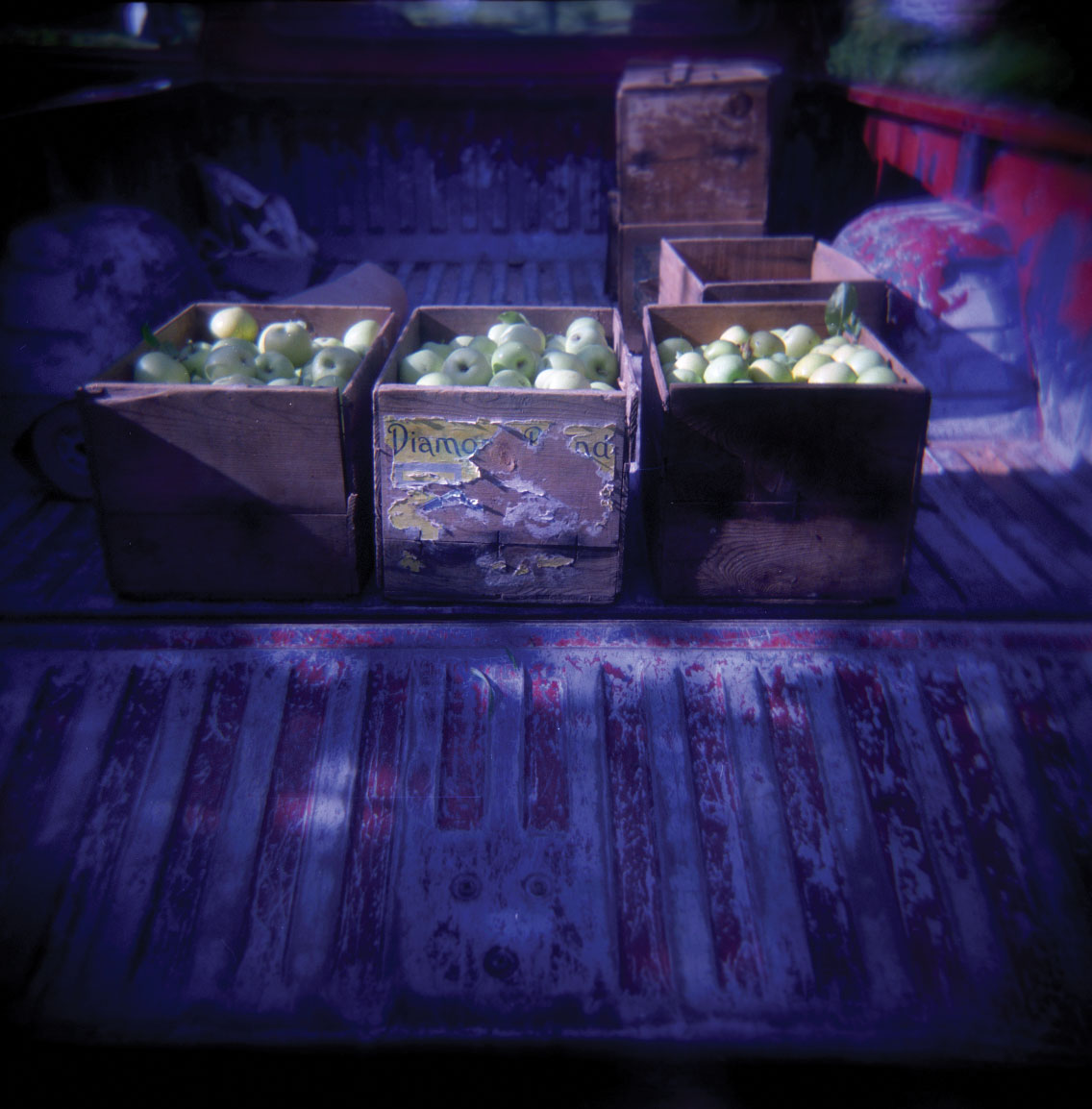

And yet I recently found myself teetering from the top of a harvest ladder, helping Carol Nigh pick apples for the Harvest Fest. Carol is the granddaughter of Evelyn Losack, Corrales’ longtime matriarch, farmer, music teacher, and hell-raiser.

Evelyn inherited a part of the family farm her grandparents started back in the 1800s. She made the apples grow by singing arias to them. She started what is now a thriving Corrales growers’ market on Sunday mornings. Evelyn had her piano students pick cucumbers and peaches instead of practicing scales when it came time to enter the State Fair pickle and fruit-basket competitions. It worked; she covered an entire wall of her house in blue, red, and yellow New Mexico State Fair ribbons.

Carol has her grandmother’s spirit. She put out a Facebook alert and was able to rally Michelle the village judge, Tanya the fire department commander, neighbors, and friends from town to bring in the harvest. She also knows the secret to country cider: Mix in a little pear with the apple.

Above: Corrales is a great place for the young and the old.

Above: Corrales is a great place for the young and the old.

Years earlier, the internship had become a job. Then my mom moved here because she loved the light. Her bones felt better. I met a man and fell in love, had a kid, planted a field. And here I stand in this cemetery doing the kind of thing that forever binds your soul to a place.

OCTOBER

Soon it will be Halloween. In between calls, the fire department will show up at Corrales Elementary to help transform the gym into a huge haunted house. On Halloween night, as soon as it gets dark, a bunch of friends pile onto our neighbor Tyson’s trailer with straw bales and blankets, hitched to the pickup. We trundle down ditch banks, singing and laughing, wine swishing and spilling out of the parents’ Dixie cups every time we go over a bump, kids yelling to the driver-parent, “Slow down!” or “Speed up!” because somebody’s pretty sure they just heard the fearsome La Llorona crying out from the bowels of the inky-black acequia. We come to a halt at the soccer fields, where hot-air balloons glow like giant lightning bugs, a big, dark field full of neighbors you can’t recognize because everyone’s in costume. It’s the annual Trick or Trunk, where Corraleños decorate their trucks, trunks, and horse trailers like haunted houses. Bags of candy overflow.

Back down the ditch we go, slowly, past the cemetery, where somehow the pickup always seems to stall out. Damn truck. We suggest the kids wait in the cemetery while we fix it. Something lurking behind one of the graves pops up and screams. The kids flee back to the hay wagon, candy and costumes flying everywhere—Go! Go! Go! And, magically, the truck starts working again and away we go, the moon above, unmoved by it all.

We emerge at last at Evelyn’s farmhouse. She’s got apple cider from her orchard on the counter, along with fruit leather dried on long summer days. We gather around the piano and she leads us in old songs: “America the Beautiful” and “There’s a Hole in My Bucket,” which has, like, 15 verses and Evelyn makes us sing every one of them, but we don’t care because it’s a fun song and somehow we know our Evelyn won’t be here for many more Halloweens. For now, we have this night, this village, and this fresh cider. Out the back door we go, singing “Corrales, mi vida, mi tierra,” the farmhouse behind us warm and filled with song, off into the night, smelling of apple and bonfire.

DECEMBER

Top-heavy, long-legged sandhill cranes, as unlikely as Kitty Hawk, awkwardly take flight from Corrales fields and become pure grace. With them, winter arrives. Early on the first Saturday of December, Commander Tanya sets to chopping 50 pounds of donated potatoes as Chief Anthony and his fire crew build a huge bonfire from downed wood. Cast-iron pots brimming with local green chile stew are buried to cook slowly among the embers as darkness comes. Kids and antique cars, twinkling with red and green lights like so many fallen stars, parade down Corrales Road. They are escorting the bishop-hatted, old-world, slimmer-than-Santa-but-with-the-same-white-beard Saint Nicholas, who, depending on the year, is driving a tractor, being pulled by a horse-drawn carriage, or sitting snug in the fire truck when it’s too cold. This is how things come about in Corrales: No one had a Santa suit when the time came to throw a village party, but Janie Foris did have a Saint Nick costume made by her mother to honor her Dutch heritage. The non-Dutch Corrales kids are always a little confused at first, but don’t seem to care once they have given their List to the Man and gotten a bag of cookies and apples in return.

Christmas carols swirl and ascend with bonfire sparks. The circle of people tightens as the fire grows smaller. Saint Nicholas visits with the last child and sits down for a bowl of hot stew.

Snow appears one day; two inches accumulate on the roads, and central New Mexico grinds to a halt. Only one thing to do: head to Perea’s Tijuana Bar and Grill, right in “downtown” Corrales. Slow-cooked, tender, earthy posole steeped in deep red chile. Tortillas made by hand every morning by Mrs. Perea, no two ever the same. It’s not on the menu, but just ask Mayling for the No. 1, green, add carne. She’ll wink and be very impressed you know about it.

Hannah, the waitress and John Perea’s right-hand person, passes out paper and scissors to those bellied up to the bar and instructs everyone to set aside their posole and IPAs for just a moment. She starts folding the paper just so—everyone please watch. She starts making intricate cuts and nicks, then folds again, cuts again. Everyone at the bar tries to follow along, folding, cutting, snipping, and then … voilà! Unfold your paper and a snowflake appears! Hannah hangs them from the vigas. They float dreamily above our heads.

During the days leading up to Christmas Eve, Mrs. Perea starts baking dozens of her bizcochitos, using the family recipe. (Trust her: Don’t risk Crisco; just use the lard.)

Her son, John, can be found most days chatting with the regulars. John Perea has one of the biggest hearts you’ll ever know. His response to most things: “We can do that.” He took over when his dad, T. C., died a few years ago. T. C. would close the place up if he felt like going fishing. John’s behind the bar today, folding brown paper bags for farolitos. On Christmas Eve, he’ll line the front of the Tijuana with the little glowing fires, up the adobe wall, all along the roof. He’ll save a few to take to his dad’s grave.

Above: Mary Spragg and August Braude mudding a church wall, an annual rite.

Above: Mary Spragg and August Braude mudding a church wall, an annual rite.

The door by the bar opens and a blast of winter charges in. The snowflakes up above flutter as if, at any moment, they will fall to our shoulders.

APRIL

Most of Corrales, it seems, is made of adobe. The beautiful and difficult thing about traditional adobe is that time wears it down—from the rain and snow to the long days holding up against a New Mexico sun. Over the past 150 years, Corraleños have come together every spring to add another layer to our Old San Ysidro Church and the wall around its courtyard. Though it was deconsecrated several years ago, it remains a beloved gathering place in Corrales for community events, art shows, and live music.

It’s a simple recipe, really—sand, clay, a handful of straw, water. But, like pie crust, it’s all in how you mix it, the tweaks here and there, the alchemy of bringing it together so that the new layer can adhere to the old.

Some years, we have to call in the experts. Otherwise it’s up to friends, neighbors, members of the Corrales Historical Society, and the Scouts. My mom and I have been showing up year after year. I set her up with a trowel and her own little pile of adobe mud, and she moves along slowly, perched on her little green stool. She likes to show the kids, including my boy, August, how to work the adobe, but they end up just throwing the mud willy-nilly at the wall, busting into giggles. Somehow, the wall gets fixed.

When you hear music performed in the old church, there’s something richer and deeper beyond what’s being played. The notes and the voices hit the three-foot-thick earthen walls and linger there for a moment, then come back. Grace notes. I like knowing that my mom’s hands and those of my son, my friends, and everyone who came before us are held within these walls.

Our plaster is never perfect. It’s a little crooked, a little too much here, not enough there. We always drive by a couple of days later to check on “our section” and see if it’s holding up. We are part of this church now.

JUNE

It’s summer. We picked dark, sweet cherries from the tallest branches. We looked for tadpoles in the acequia and found instead a turquoise snake lashed with bands of amber. There’s a certain stretch of Old Church Road that on some summer days smells of blacksmith and clothesline. Mint and epazote, lavender and sage, honeysuckle and jasmine drift through windows now open. The smell of basil will forever take me back to Evelyn’s farm. Sauce on the stove, arias in the air. It smells of our time here.

A flock of young pheasants startles from a field where alfalfa has just begun to reemerge, awakened by snowmelt flowing once again through the acequias. A Hank Williams tune drifts over from Dona and Courtney’s cow pasture. County fair will be here soon, and Dona’s convinced that music soothes and fattens the cattle. Old-style country for their 4-H cows.

If you ride fast on a red bike through the bosque by the river, slow down and look up. You are sure to spot slumbering porcupines on the tops of the tallest trees.

The night here returns to the animals. First one coyote, then another, then the whole pack. Their howls when they’ve surrounded their prey will jolt you out of the deepest sleep. Frogs awakened by summer rains sing from way down by the river. Sound seems to carry differently at night, as if on the backs of owls.

The neighborhood boys have stripped down to their underwear, flip-flops long lost to mud, and taken to the ditch. I never considered how vital a swimming hole, a field, a forest could be. To a kid, an undeveloped acre lot overrun with wild elms can transcend into a Magical Forest full of witches. Rafts of tree limbs and baling twine are ready to set sail on the Río Grande and, beyond that, the sea. An old harvest box manifests into a performance stage, a hiding spot, a bike ramp. Run through an open field and the world becomes your own.

Above: The fruits of hard labor.

Above: The fruits of hard labor.

Last night was the summer solstice. Friends gathered around a campfire in the backyard. We drank wine out of Ball jars stuffed fat with Corrales blackberries. The kids made two-tiered s’mores. Above us, Ursa Major curled up with Ursa Minor, two summer bears tumbling across the sky. A game of hide-and-seek broke out, boys and dads versus girls and moms. The count began and we fled in all directions, barefoot, some of us to the ditch. We scrunched down deep among the blackberry bushes, shooing off dogs trying to root out our hiding places, and held our breath so no one could hear us. Feel it once again: that mad delight in the pit of your stomach that you could be found and tagged “it” at any moment. Then we were shadows finding our way back to base, all safe, and it was growing late. The kids fell to bed, river hair, grass-stained feet, sunburnt shoulders, marshmallowed hands. The days are long now, and school is forever away.

OCTOBER

The years pass. Another Christmas, another summer, again, and again. My day of digging is done. The grave is ready. Four feet by four feet by four feet, down into the Corrales earth, good enough for ash remains. A lizard scuttles across the bottom and I scoop him out. Sharon goes to collect some juniper berries from a nearby tree. The medicine men love this kind, she tells me.

Earlier this fall, Mark Tafoya showed us our spot. Mark used to be the ditch boss for our acequia. Now he’s the caretaker for the campo santo, the cemetery. He likes to save the orange globe mallows and the wild purple asters. “Even if we live a long life,” he had said to me as he marked off the grave’s lines, “it still feels short.”

I breathe in what the trees of this place breathe out. My hands are calloused with Corrales’ clay, my feet rough with barefoot days. I have lines in my face from laughing too much in its sun. Its food becomes my muscles becomes my work. The water from ancient aquifers below me flows through my blood. My mouth is stained with its berries. Its frog song fills my dreamworld.

Will this always be home? It could change. Friends move away, kids grow up. Our parents die. Home is when you wake up one day and find that you’ve given yourself over to a place, and it has given itself to you.

This evening, we will put my mom’s ashes here, next to the sage, next to our Evelyn, gone a couple of years now, near the bend in the road, down by the old church. Until then, we’ve got this whole, big, beautiful day ahead of us.

“Keep the faith with all this, honey,” Evelyn told me once, and I promised her I would. We gather our shovels and head home. Someone has placed wind chimes in the tree by T. C. Perea’s grave. A breeze passes through, and they sing.

AROUND CORRALES

Where to Eat

Perea’s Tijuana Bar and Restaurant. Coldest beer in town, featuring many local microbrews and homemade New Mexican lunch. Sit at the bar to hear some stories.

Indigo Crow Cafe. Elegance meets country. Great outdoor patio under the cottonwoods, cozy fireplace, and bar. Lunch and dinner.

Las Ristras Comedor de Corrales. Great New Mexican food. Village Council meetings have been known to end early so councillors can make Taco Tuesday. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner (lasristras.com).

Hannah & Nate’s Market Cafe. Great little patio. Huevos rancheros and other local breakfast favorites; good green chile stew at lunch (hannahandnates.com).

Corrales Bistro Brewery. Outdoor patio with a great view of the Sandía Mountains. Lots of good, locally crafted beer and a live band nearly every night. Open daily for breakfast, lunch, and dinner (cbbistro.com).

Village Pizza. Seriously, the best pizza. Great patio. Lunch and dinner (villagepizzanm.com).

Sandia Bar. Great dive and local hangout. Play some pool, fire up the jukebox (find them on Facebook).

Perk Ranger Coffee House. Smoothies, homemade pastries, and gluten-free options. Breakfast and lunch (find them on Facebook).

What to Do

Corrales Growers’ Market. Local produce, meats, baked goods, flowers, and live music. 9 a.m.–noon Sundays, May–November, and first Sunday of the month, November–March (corralesgrowersmarket.com).

Music in Corrales. Concerts at the Old San Ysidro Church, September–April (musicincorrales.org).

Wine Tasting. Check out Corrales Winery, Acequia Vineyards, Pasando Tiempo Winery and Vineyards, and Milagro Winery.

Corrales Harvest Fest. September 29–30. Hayrides, local produce, corn maze, live music, hootenanny dance, art, food, parade, and wine fair (nmmag.us/corralesfest).

Annual Old Church Fine Arts Show. October 6–14 at the Old San Ysidro Church (corraleshistory.org).

Where to Stay

Corrales features three charming bed-and-breakfasts, with views of the Sandía Mountains, the Río Grande, and migrating cranes (nmmag.us/corralesbeds).