HERE IS A SCENE you will recognize. In New Mexico, something resembling this is so common, the experience may not even be mine, although I’m pretty sure it is.

My wife and I are up early, brewing coffee, while crimson and gold light up the kitchen in Technicolor Southwestern hues. An ordinary morning, beautiful enough to break your heart, unfolds beyond us in the Galisteo Valley, south of Santa Fe, when I see Sara’s eyes widen. She looks past me through the windows. I track her line of sight.

Five coyotes, three of them yearling pups like a posse of cruising teenagers, trot single-file past our kitchen windows. Backlit in the dawn, every hair on their sharp muzzles, upright ears, and floating tails is outlined in sunlight. The alpha pair—a robust male and gracile female—brings up the rear, and as that effortless coyote trot passes our windows, I note two details.

The female is familiar, an unusual coyote with a white (rather than black) tip on her tail. I’ve already registered that two of the yearlings carry that same genetic marker. This distinctive female has raised pups in the canyon below the house for at least the past three years.

The male makes me laugh. Gliding past the house as if he were on skates, his yellow eyes suddenly widen as he spots our brawny Alaskan malamute lounging on the front porch. Never breaking stride, but with a quick grimace—no time to hang out!—he shows Kodi his lovely white teeth. Kodi stares, and Sara grins. It is a wild canid show to match the dawn, and we haven’t had to go to Yellowstone or Alaska to see it. We just looked out the windows.

Difficult as it is to bump politics from the headlines these days, coyotes can manage it. In the spring of 2015, patrons of a bar in the New York borough of Queens—that’s right, the interior guts of our largest megalopolis—heard a sound overhead as they exited the building. A dozen feet above them, looking down curiously on afternoon street traffic, was a healthy coyote. In a pause between firing smartphone photos, one of them called animal control. But when the official van rounded the corner a few minutes later, the coyote glanced, whirled, and disappeared through the broken window of a nearby building, just like any garden-variety superhero.

In what has become a contender for the most intriguing wildlife story of our time, the coyote’s spread out of the West is now letting people all over America see the creatures out the kitchen window (or on the roof of a bar). Not everyone is necessarily happy when a predator lopes by; for ages, sheep and cattle ranchers have considered the coyote a sworn enemy, and now suburban and even urban dwellers grow anxious for their backyard chickens and household pets. But science doesn’t support that fear, and extermination efforts have backfired.

Escapades like hanging out above a bar in Queens or strolling into an eatery in Chicago are a walk in the park for this most American of wild canids. The story of the coyote’s expansion across America is merely the most recent chapter in the remarkable biography of an animal we have known, by turns, as a semi-deity and, during westward expansion, as the exotic “prairie wolf.” By the 20th century, some were calling the coyote the “archpredator of our time,” and it was the subject of a nasty, brutish, not-so-short war of extermination. After that came the “Coyote consciousness” interlude, a West Coast bohemian reincarnation of capital-C Coyote as a god of 1960s counterculture. The coyote may well be a real-world version of “the Dude,” and, as we all know from the movie The Big Lebowski, the Dude abides.

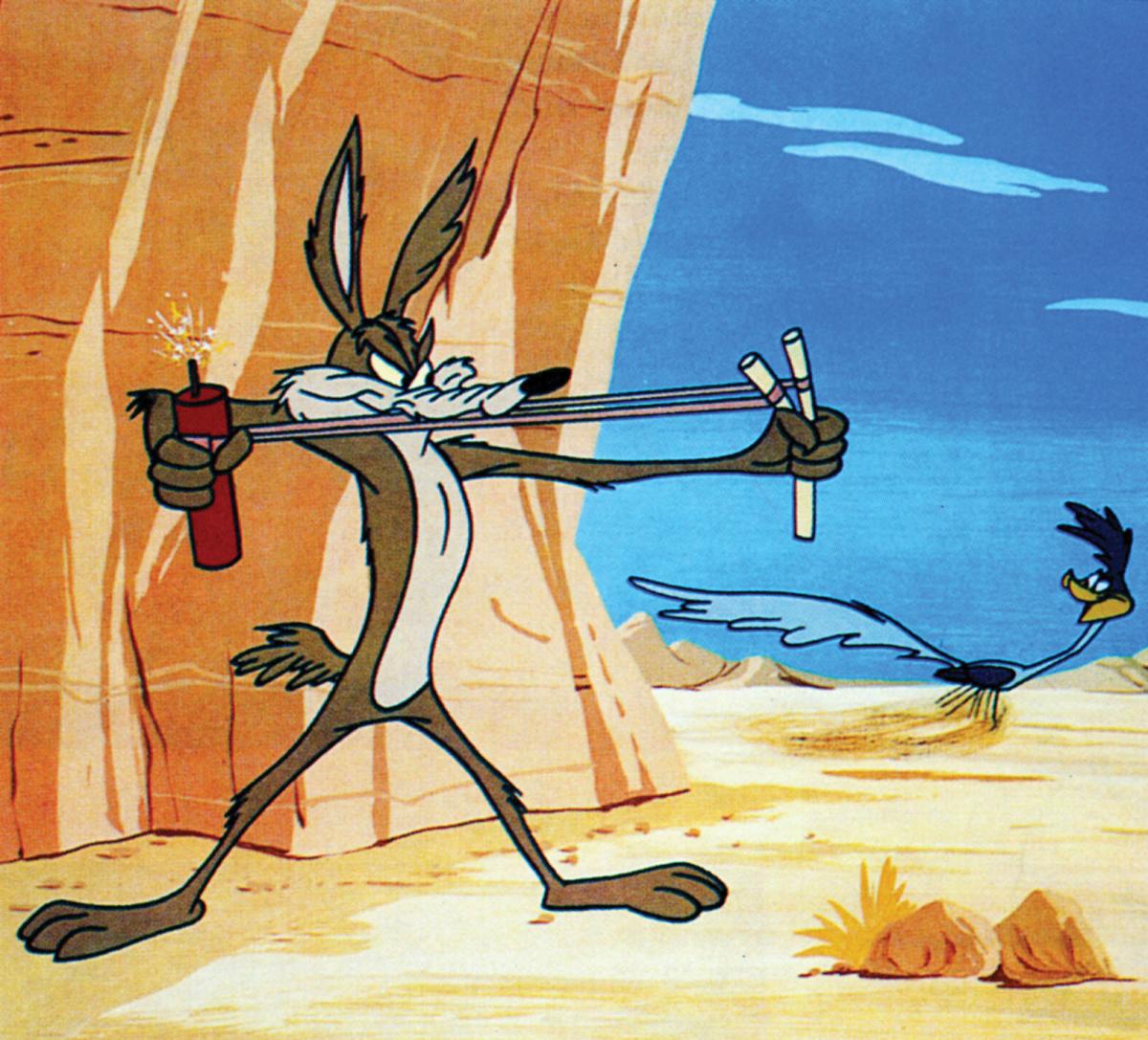

NEW MEXICO AND THE SOUTHWEST have long been critical to the coyote’s biography. Consider: In March of 1949, animator Chuck Jones made the first cartoon featuring Wile E. Coyote. That same year, New Mexico legislators chose the greater roadrunner as the official state bird. A decade later, after Smokey the rescued bear cub became the symbol of the Forest Service’s fire-prevention ads and a hero of New Mexico, politicos made the black bear the state animal. But cruise through the capital city of Santa Fe and see how many representations of roadrunners you can find. Over at the Santa Fe Depot, you may come across an idling Rail Runner, the regional commuter train adorned with a beak-into-the-wind roadrunner, but it may be your only sighting. Black bears? On murals and in art gallery windows around town, black bears are almost invisible.

But New Mexico’s most famous unofficial animal appears everywhere—from giant metal sculptures to portraits on the covers of the city’s art magazines. Its visage adorns the Coyote Café, where art over the doorway of the Cantina imagines both bartenders and patrons as cowboy-booted, hard-partying coyotes. Carved, howling coyotes sporting bandannas, however clichéd after decades, are still in stores around the Plaza. Coyotes in art, often wildly abstracted, stare with that steady coyote gaze from gallery walls up and down Canyon Road.

Above: Through the ages, coyote images have graced New Mexico life and culture.

Having written a book about coyotes, my take may be biased, but I think the coyote ought to be even more famous. If we had known that all of our campaigns to trap, poison, and shoot this “archpredator” would be useless against the coyote’s powerful genetic ability to recover, if we had understood the coyote’s ancient role in nature, we might have stopped programs such as New Mexico’s ill-considered 2001–2003 effort to protect deer by killing coyotes. These plans simply don’t work. If city dwellers knew that urban coyotes prefer rats, mice, and rabbits to cats and dogs, would our attitudes change? If we knew coyotes better today, if we saw their lives clearly, if we understood how closely they are interwoven with us, we might grasp why an “unofficial” animal has become a totem-by-popular-choice in Santa Fe and New Mexico. The coyote may have bigger aspirations, though. Today it’s no mere symbol of the West; coyotes have gone national.

The hurdle to appreciation of coyotes as truly special American animals is that most Americans, even Southwesterners, know next to nothing about them except that they howl (and yelp and bark), that Indians told stories about them, and that one used to fall off cliffs in Saturday-morning cartoons. So let me tell you a few things you didn’t know.

The coyote’s evolutionary roots are purely American. Unlike the iconic bison, whose origins lie in Asia, the coyote springs from a family of animals called the Canidae, which emerged in the American Southwest 5.3 million years ago. All the world’s wolves, jackals, dingoes, wild dogs—and our family pets—had their beginnings right here, millions of years ago. But unlike most of them, coyotes come from a line of canids that never left America. Wolves migrated across the land bridges to much of the world, where they continued to evolve before returning to this continent 30,000 years ago. Some 800,000 to a million years ago, a close coyote relative migrated halfway around the globe to Africa and the Middle East, becoming the golden jackal. Want to understand the long span of American history? Get to know the canid that never left.

The coyote/human relationship is also ancient. Humans arriving in the Americas 15,000 years ago confronted an ongoing extinction of many of our most dramatic species. Mammoths, camels, horses, and lions all disappeared. But one of the survivors caught the attention of the first people, and soon they started thinking of it as an avatar—a stand-in for humans in the imagination. In their stories about him, Coyote emerged not just as the deity responsible for creating North America, but as the main character in the oldest literature in American history. Across hundreds of generations, wherever coyotes ranged, Native peoples such as the Puebloans and Navajos told stories about Coyote to explain how the world works. With literary origins that go back 10,000 years, Coyote is a god out of Paleolithic America.

These stories survived thousands of years because, frankly, they were potent, often comic shout-outs to human nature. Since folklorists began collecting tales a century ago, we have referred to Coyote as a “trickster,” and for a century we’ve been missing the point. In Coyote literature, the trick isn’t the thing. It’s why the trick works that matters. Invariably, it’s a consequence of our classic flaws: selfishness, narcissism, lust, striving for status. Coyote, it turns out, is an unusually useful god for telling us who we are.

IN TRIBAL HISTORY, THESE events no doubt happened many times, but a Navajo oral tradition from the 1860s says that what finally enabled their leaders to negotiate the people’s return from Bosque Redondo to their homeland (see “To Touch the Soil,” p. 42) was the Coyote Way ceremony they performed before meeting with American military leaders.

Coyotes were a many-faceted puzzle for Americans heading west. In 1900, New Mexico transplant and nature writer Ernest Thompson Seton published his “Tito: The Story of the Coyote That Learned How,” in Scribner’s magazine. The story was an allegorical attempt to explain how, with bison, wolves, grizzlies, and many others nearing extinction, the coyote wasn’t merely surviving but spreading. At the same time, New Mexico rancher Arthur Tisdale made an initial appeal to the federal government to rescue ranchers from predators. After establishing an Eradication Methods Lab in Albuquerque, the government launched a poisoning campaign that mostly wiped out wolves by the 1920s, then turned to the supposed “archpredator of our time.” What followed was 50 years of ever more diabolical poisons for exterminating coyotes from the world.

Above: With one glance, a coyote slinks away.

The result was utterly counterintuitive. Instead of disappearing, coyotes began to show up in every state in the Union. We had launched coyote extermination before bothering to do any science about the animal’s role in the world or how it responds to such persecution. When biologists finally got around to such, they were stunned. It emerged that the coyote’s long history of living with wolves had given it evolutionary adaptations that were only released by harassment—namely, a propensity to have larger litters and an inclination to colonize widely as singles and pairs. Leave coyotes alone and their populations stabilize. Try to exterminate them and high-gain survival mode kicks in.

Which means—and why do things like this surprise us?—that if you want to live in America, you need to get along with coyotes. I’ll go further: You need to appreciate them as a lesson from the continent. A coyote howl is the original national anthem.

As Sara and I watch our local pack trot down the driveway, Chuck Jones—who long had a gallery on Palace Avenue, in Santa Fe—comes to mind. Jones developed Wile E. Coyote at the same moment that the California Beats were discovering the Coyote tales, so it’s no shock that Wile E. functioned as yet another coyote avatar. (Obsession and humiliation were his specialties, but he also served as an object lesson in why you shouldn’t be a gullible consumer, particularly of Acme products.)

Before they leave the yard, the female with the white-tipped tail turns and stands broadside. Her yellow eyes meet my gaze and a thought forms: I’m not sure who is serving as an avatar for whom.

HOW COYOTE GOT HIS NAME

Spanish explorers, including Francisco Hernández, wrote descriptions of coyotes as early as 1651, but for most Americans, the introduction came by way of the 19th-century Lewis and Clark Expedition. Americans knew wolves from Europe and the Atlantic shore. But because they were in the West, coyotes were a mystery. Upon seeing their first ones on the edge of the Great Plains in 1804, Lewis and Clark initially believed they were foxes. But when they shot one and examined it, they decided it was in fact some new kind of wolf. Thus the name “prairie wolf” lingered for a century.

New Mexico disabused Americans of the notion that prairie wolf was the new canid’s proper name. The founders of Santa Fe had brought north with them the ancient Aztec name for the animal: coyotl (with a silent l), in the Nahautl language. But by the 1820s and ’30s, when Santa Fe traders like Josiah Gregg began writing about the animal, Spanish speakers had Hispanicized it into three syllables—coh-yoh-tay.

The Spanish pronunciation was the one most Americans took home, and in 1873 it reached a large swath of the reading public via Mark Twain’s book Roughing It. Twain’s phonetic help indicates that, by then, the word had been Anglicized into ki-YOH-tee. But a second pronunciation, courtesy of Arkansas and Kansas trappers operating out of Taos, also spread through the hinterland. Maybe the trappers thought three syllables gave the coyote too much credit, so they returned to the Midwest and the South with a two-syllable pronunciation, KI-yote, thereby creating a 200-year-long urban/rural divide.

HOWL ALONG

No coyotes in your backyard? Wildlife West Nature Park, in Edgewood, east of Albuquerque on I-40, invites you to not only meet its coyotes (plus foxes, bears, raptors, turtles, cougars, and more) but learn to howl just like one. Open 10 a.m.–6 p.m. from mid-March through October and noon–4 p.m. from November to mid-March (87 N. Frontage Road, Edgewood, 505-281-7655, (wildlifewest.org).