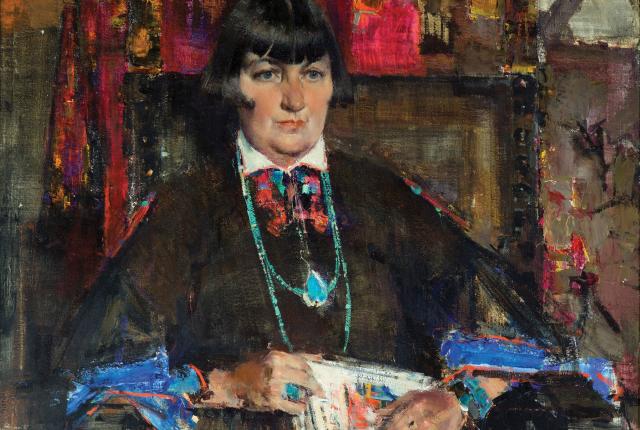

Above: Nicolai Fechin, Portrait of Mabel Dodge Luhan,c. 1927, oil on canvas, the Anschutz Collection.

WHEN MABEL DODGE LUHAN died, in 1962, Taos and America paid little attention. However famous and influential she had been in her early-20th-century heyday, it no longer seemed to matter. In her later years, she’d already started to seem more like a legend than a real person. She was associated with a Taos-specific strain of utopianism, free love, and a vigorous approach to arts and cultural patronage, and her house remains a landmark to this day. Beyond that, appreciation of the essence of Mabel and her contributions to New Mexico and America have long been mainly the domain of a few scholars and dedicated fans.

But there is to Mabel Ganson Evans Dodge Sterne Luhan (she had several husbands) a larger story: one about a great creative force in American arts and letters, a central participant in a truly American artistic movement, a linchpin in New Mexico’s integration into a broader national and international conversation, and a character as original as any, in a part of the country filled with them.

As if to finally prove the point, Mabel editor and biographer Lois Rudnick, along with longtime collaborator MaLin Wilson-Powell, has curated a major new museum exhibition presenting the woman whom the painter Marsden Hartley described as “a real creator of creators.” Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company: American Moderns and the West, which runs from May 22 to September 11 at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, unveils its subject in a way she’s never been seen before—not as a caricature of feminism, spiritualism, or imperialism, as she’s often been portrayed, but as herself, immersed in the novel and unorthodox worlds she helped bring forth.

Based on a thousand pounds of scrapbooks, plus photographs, books, letters, poems, paintings, and sculptures from those she influenced, hosted, and encouraged—Anglo, Hispanic, and Native alike, and including artists like John Marin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Awa Tsireh, and Pop Chalee—the exhibition moves from Taos to the Albuquerque Museum of Art and History, October 29–January 22, 2017, and ends in her hometown of Buffalo, New York.

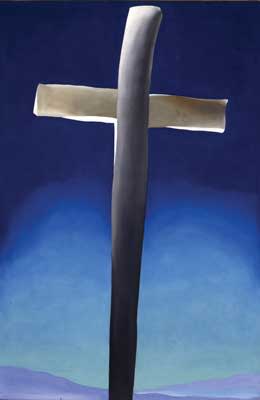

Georgia O’Keeffe, Grey Cross with Blue, 1929, oil on canvas, Albuquerque Museum of Art.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Grey Cross with Blue, 1929, oil on canvas, Albuquerque Museum of Art.

It’s an auspicious moment for the exhibition, spearheading as it does a season of high interest in its subject that includes the recent publication of Rudnick’s second edition of Mabel’s memoirs, Intimate Memories; a new play by Stephen Lowe, Altitude Sickness, based on an unfinished D. H. Lawrence satirical play about Mabel and produced by the Fusion Theatre Company; and the planned release this summer of Awakening in Taos, a documentary on Mabel’s spiritual conversion. In August, the Harwood itself is putting on a new Mabel-focused opera by the award-winning composer and librettist Nell Shaw Cohen, and a fashion display by Project Runway runner-up and Taos Pueblo native Patricia Michaels, entitled “The Heart of Mother Earth Gives to the Soul of Women in the Arts Who Touched Taos.”

So if Mabel hasn’t really been understood or gotten her due, well, that’s all about to change.

Mabel’s entire life was spent trying to remake the world into something more vibrant and exciting than the one she was born into. She began with her childhood home in Buffalo, which she described years later as the place “where the occupations were so unvaried and the imaginations so little fed.” Born into an upper-class family mired in the Victorian niceties of the late 1880s, she presents a picture of a girl exquisitely sensitive to the emotional coldness, constraining propriety, and utter banality that characterized her day-to-day life.

Mabel wrote that the tulip bed in the center of the yard was “a symbol for the rest of the house. It was all ordered and organized, nothing was left to fortuitous chance, and no life ever rose in it taking its own form. My mother was too good a housekeeper for that.” She did finally win a “little room up the stairs” to do with what she wanted, and found in the reshaping of that space “the natural growth of a personality struggle to become individual.” And she got hooked on reinvention.

A few years later she started reshaping on a grand scale. First was the palace of Villa Curonia, where she moved with her second husband (her first having given her a son before dying in a hunting accident). There, in the heart of Tuscany, she dived headlong into fin de siècle European decadence. In a place where “everyone played with the past,” she played hardball. She dressed the part of Catherine de Medici (whose family had owned the house), had her portrait painted in Renaissance style in a room where the “sun shone on tiger skin and roses,” and redecorated to suit her image, of herself and her life: thick brocades on floors and walls, gold carvings, damask, and lots and lots of silk.

Mabel Ganson, age 18, at her

coming-out party.

Then she went in search of people who could fill in her vision of Renaissance excess. She lured her friend Gertrude Stein from Paris by writing, “Please come down here soon—the house is full of pianists, painters, pederasts, prostitutes, and peasants. Great material.” She reported, however, that her husband “did not like the people I was collecting.”

In the end, Mabel found Italy boring. She likened the people she knew there to “portraits in a gallery.” “They were,” she wrote, “just the casual figures of Florentine life in the early days of the 20th century. Finally I said to myself: ‘I have seen them.’”

Her next stop was 23 Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village. Naturally, Mabel attended to a decorative remaking, completely in white; she imagined the house as a “repudiation of New York,” a refuge. She translated her Italian mode of entertaining—theatrical, intentional, and edgy—into her own distinctly American idiom. Her invitees included basically every avant-garde painter, writer, thinker, experimentalist, and reformer who got near her gravitational pull. She claimed that her guest list included “Socialists, Trade-Unionists, Anarchists, Suffragists, Poets, Lawyers, Murderers, ‘Old Friends,’ Psychoanalysts, I.W.W.’s, Single Taxers, Birth Controlists, Newspapermen, Artists, Modern Artists, Clubwomen, Woman’s-place-is-in-the-home Women, Clergymen, and just plain men.” The gatherings violated almost every Victorian social stricture on the books—regarding race, class, occupation, sexual preference, and public morality—and made her famous as a salon hostess.

Mabel also threw herself into social and cultural causes that appealed to her sense of rebellion and her need to be needed, the most notable of which was the 1913 Armory Show. The first exhibition in the United States of Modern artists, many never before seen outside of Europe, the exhibition was described in the New York Tribune with a headline that read, “A Remarkable Affair, Despite Some Freakish Absurdities.” In other words, right up Mabel’s alley.

“As soon as I collected a few pictures from here and there,” Mabel wrote, “and had written a check for five hundred dollars [to one of the founders], I felt as though the exhibition was mine ... It became, overnight, my own little revolution. I would upset America; I would, with fatal, irrevocable disaster to the old order of things.”

But then came the Great War, and with it the profound sense of disillusionment that marked the end of progressive innocence. And so, when Mabel’s third husband, the sculptor Maurice Sterne, wrote to her in 1918 from Santa Fe (where she had sent him to be out of her hair), begging her to come see for herself the possibilities of a different world, she got on the train.

After a few days of dealing with the artists and women much like herself who made up the Santa Fe scene, she complained to her husband, “All these people! I want to get away somewhere, I don’t like living on this street and going to tea parties.” She decided to decamp to Taos, telling him, “You needn’t go along if you don’t want to, but I’m going. Tomorrow.” And so off they went.

That 70-mile trip along the rugged, beautiful road following the Río Grande had an impact on Mabel: “‘Holy! Holy! Holy!’ I exclaimed to myself. ‘Lord God Almighty!’ I felt a sudden recognition of the reality of natural life that was so strong and so unfamiliar that it made me feel unreal. I caught a fleeting glimpse of my own spoiled and distorted nature, seen against the purity and freshness of these undomesticated surroundings.”

On arriving, Mabel wrote that her life “broke in two”: the before and the after. It’s the after that altered the course of American arts and letters, and propelled New Mexico into a rest of the world. Although the Harwood exhibition includes some minor items from Mabel’s childhood and adventures in Italy and New York, it is the after period that sits at its heart.

Possibility always excited Mabel, and she was now very excited. “In this country, life could come to one more concretely than in other places,” she wrote, imagining a world where words and ideas and symbols were no longer just things flung around, but became real. It was, in other words, just the place for Mabel.

As usual, she moved quickly. In short order, Mabel cut her hair to match the style of the women at Taos Pueblo, adopted the local dress, and found herself drawn to a new man—Tony Luhan, a married Taos Pueblo Indian. “Maurice seemed old and spent and tragic,” she wrote, “while Tony was whole and young in the cells of his body, with his power unbroken and hard like the carved granite rock.”

While Sterne failed miserably to operate a shotgun, Luhan drummed every night to summon Mabel to his tepee, so before long, Mabel sent her husband away; Luhan divorced his own wife and the two married. The drum survives and is in the new exhibition.

Mabel and Tony Luhan, c. 1920s, Mary Austin Collection, Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The marriage, considered radical even for a woman of Mabel’s reputation, did not go unremarked upon in the rest of the world. A typical newspaper story headline read, “Why Bohemia’s Queen Married an Indian Chief. Fascinated by Paintings of Savage Life, the Former Mabel Dodge Sterne Finds Its Reality So Much More Delightful That She Accepts a Pueblo Brave for Her Fourth Husband.” They got the rationale and terminology wrong, but it sold papers. Mabel’s former husband Edwin Dodge wrote dryly, “Lo, the poor Indian.”

Together Luhan and Mabel transformed a low-slung adobe near the pueblo into a rambling three-story house that included 14 guest bedrooms, as well as five guesthouses across the property’s 12 acres. It was called Los Gallos, in honor of the ceramic roosters perched on the roof.

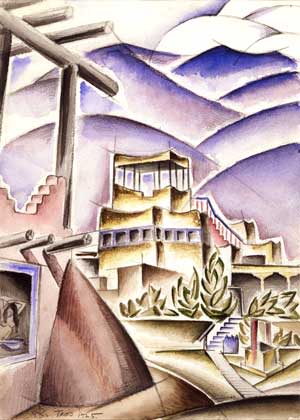

Arnold H. Rönnebeck, Casa Luhan,

Arnold H. Rönnebeck, Casa Luhan,

Taos, 1925, watercolor.

Now Mabel was ready to resume her destruction of the old word, or as Rudnick puts it, effect “the redemption of Anglo civilization from its urban-industrialist bias, its individualist and materialist credo, and its Eurocentric vision of culture.” The call went out.

And what a response she had. Among the artists and thinkers who came to visit were Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Ansel Adams, Rebecca Strand, Willa Cather, Elsie Clews Parsons, John Collier, Jean Toomer, Mary Austin, Carlos Chávez, Carl Jung, Martha Graham, Aldous Huxley, Robert Edmond Jones, Paul Strand, and Witter Bynner—along with Mabel’s traditional claim to fame, D. H. Lawrence.

The house in isolated northern New Mexico became not only what many of the surrounding conservative Catholic and Native communities thought of as a den of iniquity (free love, after all, was part of the Modernist package) but also the hub of a vital creative network. The question is: Why?

Mabel needed collaborators, ones gifted in seeing the world in new ways, who could appreciate the lessons she felt the Pueblo Indians had to teach white America: that simplicity, peacefulness, and spiritual integration could cure them and her of what she called their “epoch.” Through their reintegration as “whole beings,” they could heal a wounded America and world.

But it wasn’t just the pueblo that fascinated Mabel and her guests. After a rough start, she found the intense spiritualism of Hispanic Taoseños intoxicating; she had a particular interest in the Catholic Penitentes whose morada was nearby. These fascintions bore fruit, as Mabel’s guests strove—with her constant encouragement—to incorporate into their work not only the spiritual gifts of the wide-open spaces and big skies, but the land and its people.

Walter Ufer, Hunger, c. 1919, oil on canvas, Gilcrease Museum.

Walter Ufer, Hunger, c. 1919, oil on canvas, Gilcrease Museum.

Her guests painted and photographed and wrote, capturing the symbolism of the local Native and Hispanic ways, but often, too, quotidian scenes of life in the northern mountains. Marsden Hartley’s work in the exhibition offers two examples of this range: a stark appropriation of Native imagery in An Abstract Arrangement of American Indian Symbols (1914–15) and a classic depiction of mesas, mountains, and arroyos folding over one another in Landscape, New Mexico (1920). The exhibition includes a wooden cross from the area that strongly suggests a connection to the crosses that O’Keeffe painted. And of course the famed San Francisco de Asis Mission Church in Ranchos de Taos shows up in paintings and photography, most notably with Paul Strand’s platinum prints.

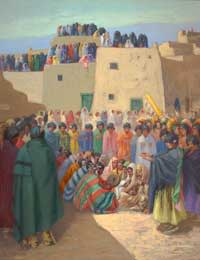

Burt Harwood, Comanche Dance, Taos Pueblo, 1915–1925, oil, Harwood Museum of Art.

Burt Harwood, Comanche Dance, Taos Pueblo, 1915–1925, oil, Harwood Museum of Art.

Martha Graham, El Penitente, 1940, gelatin silver print, University of New Mexico Art Museum.

Martha Graham, El Penitente, 1940, gelatin silver print, University of New Mexico Art Museum.

Mabel also organized trips out into the country or into the pueblo (with Luhan serving as guide and facilitator), invited people passing through to come in and speak, stirred up trouble in people’s relationships, and engineered conversations between locals and visitors. The most famous of these is probably the long talk between the psychoanalyst Carl Jung and the Taos cacique Antonio Mirabal on symbolism and dreams. She was both a hostess and provocateur.

Only D.H. Lawrence, of all the men in the world, could “really see this Taos country and Indians, and ... describe it so that it is as much alive between the covers of a book as it is in reality,” Mabel wrote. She begged him to come, and finally he did. Arriving in the fall of 1922, accompanied by his wife, Frieda, Lawrence entered Mabel’s life and the lore of the state. Mabel was ready, she thought, for all his “dark gods” and what they could do for her, both intellectually and physically.

Unsurprisingly, Mabel had a tense relationship with Frieda, as well as with Lawrence himself. He and Mabel had strong personalities and clashed repeatedly: He said she was the only person whom he could imagine murdering. In an effort to get him to stay and write, she offered him a 180-acre ranch nearby. He declined the deed to the property (Frieda accepted), but stayed there for a few months—long enough to enjoy New Mexico’s charms. He never did succumb entirely to Mabel’s.

The experiences Mabel engineered and the visions that underlay them, as well as the force of the timeless imagery and sensibility of the land, provided the foundation for what scholars call Southwest Modernism. But the results weren’t, as the new exhibition makes abundantly clear, just another new Anglo view of the world, but something exceptional. Wilson-Powell calls it the birth of “native modernisms.” Mabel was sure that the Native and Hispanic artists had things to teach her guests: that not only were their ways of life models for how Americans might live, but their artistic traditions had something valuable to offer as well. She put her time and resources on the line to prove it.

In sending her husband’s niece Merina Lujan (later known popularly as Pop Chalee) to study painting with Dorothy Dunn at the Santa Fe Indian School, Mabel’s role as patron grew from buyer of art to creator of artists. She kept her eyes open for up-and-coming Native artists whose approach resonated with her, and not only bought their work but commended it to others. Many of her guests left with full trunks and the beginnings of museum exhibitions all over the country.

Mabel organized the first exhibition of Pueblo painting at the then-new Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe in 1920. There was work by Ta’e (a former janitor who became one of the great early Native water-colorists), his nephew Awa Tsireh, the Hopi artist Fred Kabotie, and the Zia painter Ma Pe Wi, among others. Mabel owned all the pieces, and she later sent the exhibition on the road to New York (along with her collections of Hispanic retablos and bultos—the first time this devotional work had been treated as fine art).

It’s the source of some lingering animosity toward Mabel that, as Carmella Padilla, a noted interpreter of Southwestern culture and history, has written, Mabel had “no qualms about making an authoritative assessment of a tradition she knew little about.” But this wasn’t a failing unique to her or her time, and regardless, her stature and energy paid dividends. Not only did Mabel help ensure that Native and Hispanic art was taken seriously and considered essentially American, but she advocated for the people themselves. Collaborating often with John Collier, who went on to become the commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, she spent 20 years fighting for Native rights. Her writing, often for newspapers and magazines back east, gave her skin in the game, and she tirelessly publicized not only the independent character and quality of Native culture, but the importance of land rights in protecting and maintaining that culture.

Inevitably, Mabel’s utopian project of healing the world failed. As she grew older, she penned a few nostalgic pieces about what could have been, but after the 1950s, Taos had moved on. It was still considered a place for creative people, and its beauty certainly hadn’t diminished, but its representative characters had dispersed. After a couple of small strokes, Mabel was rarely part of the ebb and flow of Taos life. She and Luhan spent time traveling, and when at home they kept largely to themselves.

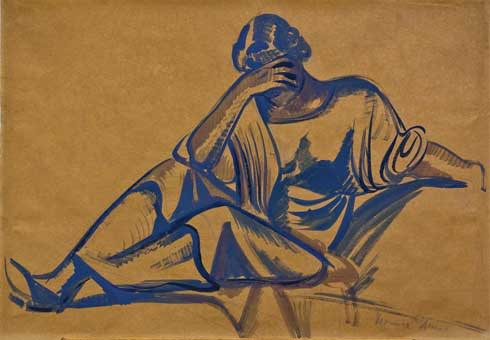

Maurice Sterne, Mabel Dodge, 1917, ink wash on paper, collection of J.B. Lane.

Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company isn’t so much about a collection of individuals as it is about the intense creative world they found themselves part of, and helped mold. But it does reveal a woman whose place in American and New Mexican cultural history was as more than a patron of the arts or an experienced and skillful hostess. She was undoubtedly “a creator of creators” as well as a creator in her own right. Her talent wasn’t the same as many of those she collected, but it shared some of the same qualities. She, like them, sought new ways of exploring reality, of making visions true things, of finding meaning and purpose. Her creation was a sort of cultural infrastructure—the places, support, and interactions necessary for others to do their own transformative work. It is one that clearly endures.

Rudnick has written that because of Mabel, Taos became “one of the centers of modern art, literature, patronage, and Native American rights activism in the nation.” But Mabel’s new—or newly understood—legacy is at once a thing of history and a call to the present. Wilson-Powell talks of Mabel helping create a worldly and connected New Mexico, one that was at once sophisticated and full of unharnessed raw possibility. Mabel recognized the continuing power of ideas and culture to be valuable in their own right, worth nurturing and growing. That legacy holds true today as well.

When she died, in 1962, Mabel had survived to the end of what Padilla calls an “epic cultural transition,” one she had helped bring about. A few years later, America, and Taos, would be in the midst of another great cultural shift. Mabel’s house would pass to Dennis Hopper and a whole new crop of those hoping to escape the world and create something new.

NEED TO KNOW: All Things Mabel

Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company: American Moderns and the West opens at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos on May 22 and runs through September 11, then will be at the Albuquerque Museum of Art and History from October 29 through January 22, 2017. The exhibition’s accompanying book of the same title (Museum of New Mexico Press, 2016) includes essays on the art, culture, and history of Mabel and the world she wrought. Consult mabeldodgeluhan.org for more information.

The Harwood Museum has put together a travel itinerary that includes O’Keeffe’s Ghost Ranch, the Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company exhibition, a meal at Eloisa Restaurant, and accommodations at the Inn and Spa at Loretto, in Santa Fe, and El Monte Sagrado Resort and Spa, in Taos. mynm.us/artpackage

Altitude Sickness, a new play by Stephen Lowe, produced by the Fusion Theatre Company, premieres at Taos Center for the Arts May 19. (575) 758-2052; tcataos.org

A new opera about Mabel’s early years in Taos, by award-winning composer/librettist Nell Shaw Cohen, opens at the Harwood Museum on August 12 at 5:30 p.m. (575) 758-9826; harwoodmuseum.org

“The Heart of Mother Earth Gives to the Soul of Women in the Arts Who Touched Taos,” a fashion display by Project Runway runner-up and Taos Pueblo native Patricia Michaels, takes place August 18 at 7:00 p.m. at the Harwood Museum. (575) 758-9826; harwoodmuseum.org

The Mabel Dodge Luhan House Historic Inn and Conference Center is a Taos institution whose robust schedule of workshops stays true to its namesake’s mission of inspiring creativity. 240 Morada Lane, Taos; (800) 846-2235; mabeldodgeluhan.com

The D. H. Lawrence Ranch, 20 miles north of Taos, is open to the public on a limited basis. (575) 770-4830; dhlawrencetaos.org

FURTHER READING: “Lawrence of New Mexico”: In 1936, Mabel wrote a piece for this magazine as an introduction to Lawrence’s own paean to the state, both of which are available at mynm.us/luhanlawrence.

“Looking for Lawrence”: Inspired by Lawrence’s vision of the state, Henry Shukman found that much of his countryman’s NM experience was still relevant in the 21st century: mynm.us/lookingforlawrence.