“YOU GOT EYES,” Jack Kerouac wrote to photographer Robert Frank in 1958. Anyone exiting Journey West: Danny Lyon—an exhibition at the Albuquerque Museum, on view through August 27, 2023—might say the same of Lyon, a Bernalillo-based photographer who once lived with Frank.

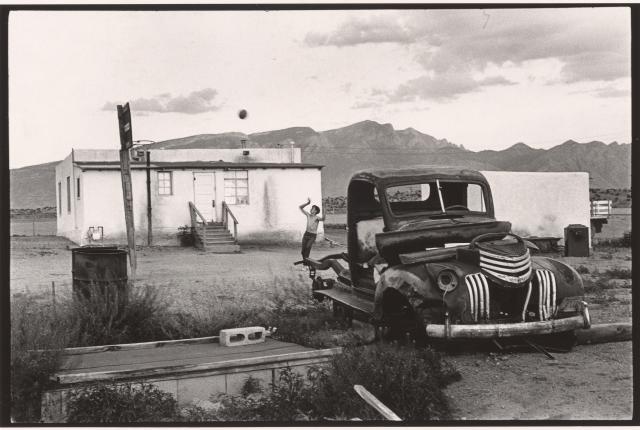

Featuring 175 photographs, montages, and films that span Lyon’s career from the early 1960s onward, Journey West opens with a dedication to the two men—one from Chihuahua, one from Albuquerque—who built Lyon’s adobe home. That specificity provides a grounding for Lyon’s lens, as do the self-penned snippets that accompany the images. “More than anything, I came to New Mexico to be free,” he writes. In the exhibition, he and his camera hop from Shiprock to Cabezon to Ratón, revealing sun-bleached mesas and hoodoos, colorful auto graveyards, freewheeling carnies and roller-derby queens, and the youthful antics of a group of brothers, cousins, and pals in Sandoval County.

The show’s seven sections—A History of Bernalillo, Journey West, Burn Zone, The Wilderness, Empathy, Protest, and Narrative—place photographs taken farther afield (a teenage boy holding a puppy in Knoxville, Tennessee; a Zapatista peace conference in Chiapas, Mexico) in a visual dialogue with images of New Mexico, highlighting Lyon’s universal ability to see. Themes emerge: the tender humanity of his subjects, the rugged beauty of his landscapes, and the ultimate fragility of both.

Before the Brooklyn-born Lyon arrived in Bernalillo in the early 1970s, he’d already amassed a searing body of work as the first photographer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). His access allowed him to document the most important events of the Civil Rights Movement. As a pioneer of the New Journalism movement, he embedded himself with the Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club, becoming an official member, and was a roommate of both Frank and Representative John Lewis at various times. “New Journalism is all about not trying to pretend that photography is objective,” says Josie Lopez, Albuquerque Museum head curator. “He’s intentionally putting himself in the story, and that makes it messy. But it also makes it more honest.”

A previously unexhibited and unpublished 2020 photograph of Lewis in bed seven months before his death is a tear-jerking standout. Wrapped in homemade quilts, wearing a plain white T-shirt, Lewis gazes unflinchingly at the camera, his worn face laden with the pathos that comes with a lifelong civil rights crusade. Here are three more indelible images from Journey West.

Bernalillo Ditch, 1971

Lopez says that after an Albuquerque Museum staff walk-through of Journey West, a coworker turned to her and said, “This show touched me more than anything we’ve ever done because this is my culture.” In this light-and-shadow-laced image of a boy diving into a Río Grande–fed ditch, you can almost smell the dirt and feel the summer breeze. For Lopez, who grew up in Albuquerque, the timeless photo conjures her mother’s voice saying, “La Llorona will get you,” if you play in the ditches.

Navajo Pool Room, Gallup, New Mexico, 1970

Many of Lyon’s photos have a cinematic quality, and his 1985 film, Willie, is so gorgeously composed that each frame could stand alone as a photograph. His 1970 capture of three men playing pool in Gallup speaks to his compositional ability, from the horizontal lines of the cue sticks to the focal orbs of the billiard balls. “It’s stunning, the way he’s using light and line and perspective,” says Lopez. The fluorescent-noir quality of the setting amplifies the drama.

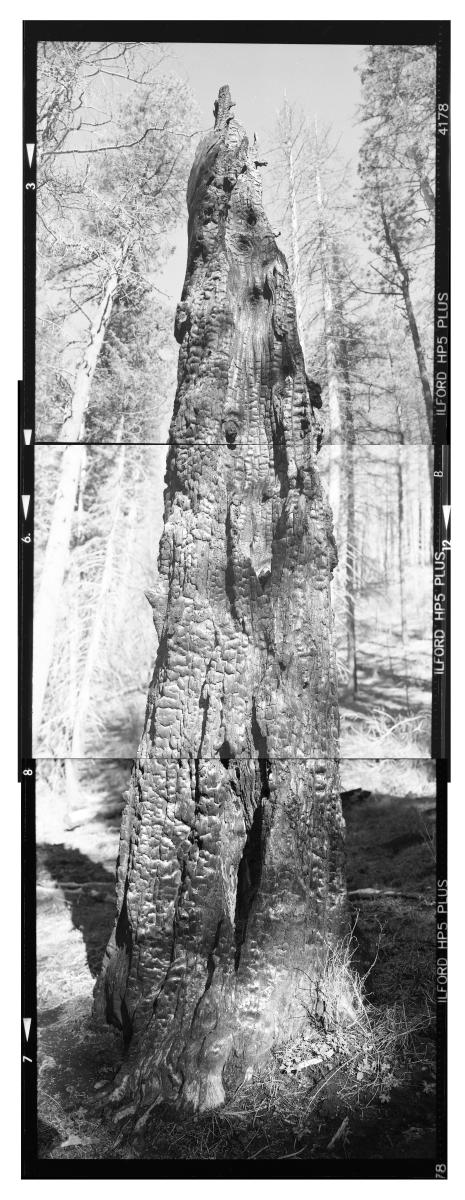

The Remains of a Ponderosa Pine Destroyed in the Las Conchas Fire, 2011

This triptych image of a still-standing burnt pine tree in the Jemez Mountains, taken two years after what was then the largest fire in New Mexico history, speaks to both the vulnerability and resilience of nature amid climate change. Each panel invites the viewer to examine in detail the mottled devastation of wildfire, which imprints its own bleak brand of beauty on the landscape.