Above: Bullets flew across this road during the Lincoln County War. Photograph courtesy of Timothy Roberts.

THE RIO BONITO PUSHES THROUGH a spring-fattened bosque, adding a palette of varying greens to the rocky bluffs that frame the southern New Mexico town of Lincoln, about an hour west of Roswell. Historic homes, shops, and the courthouse still stand, but today they offer graceful lodgings, craft brews, and documentary films. The narrow battleground of the 1878–81 Lincoln County War, a dirt road once damned by President Rutherford B. Hayes as “the most dangerous street in America,” is now a two-lane federal highway that anyone can safely amble across.

Billy the Kid—alternately portrayed in books and movies as a notorious outlaw or a charismatic freedom fighter—still stars in a down-home pageant produced every August. His tintype grin appears on storefronts, T-shirts, and shot glasses. You can IG yourself next to his life-size image at the courthouse museum or down a pint of Billy the Kid Amber, a top seller at the one-year-old Bonito Valley Brewing Company. Here in the Lincoln Historic District, you can hitch up to some reliable Wi-Fi, but legend pays the bills. The Lincoln Historic Site operates a museum, visitor center, and art gallery, along with six other buildings. When I check into the Wortley Hotel, a bed-and-breakfast that fed Deputy Sheriff Robert Ollinger right before Billy shot him dead from a second-story courthouse window, I find literature that promises, “No guests gunned down in 135 years."

Above: Visitor step back in time at the Tunstall Store. Photograph courtesy of Timothy Roberts.

Above: Visitor step back in time at the Tunstall Store. Photograph courtesy of Timothy Roberts.

Even better news for me, the document proclaims, “If you enjoy night life, bright lights, hustle & bustle and fast living, we don’t have any of that here.” While I do plan to pop into the microbrewery to sample some of the town’s new groove, I’m here on serious business. I want to reconcile what I thought I knew about the Wild West with what historians and the people who live in a town that commemorates it say today.

FOR YEARS, I SIDED with the Billy Club, a metaphorical grouping of those who buy into the romanticism of a misunderstood man-child fighting for justice in an unjust land. We ran counter to those who considered William H. Bonney (aka Henry McCarty, Henry Antrim, and Kid Antrim) an illiterate, bloodthirsty cop killer. Tim Roberts has met people from both camps. Deputy director of New Mexico Historic Sites, he previously oversaw its Lincoln outpost as well as nearby Fort Stanton, and he and his young family live a few doors down from the courthouse. Two years ago, he worked with descendants of Sheriff William Brady to place an “end of watch” marker commemorating Brady’s and Deputy George Hindman’s April 1, 1878, deaths at the hands of the Kid’s gang. Later, he saw someone spit on it.

Roberts and his team dedicate themselves to telling a deeper and wider history. It reaches back to the Ancestral era and includes the Mescalero Apache, Hispanic settlers, Anglo ranchers and merchants, Santa Fe politicians, and the African American Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Stanton. “It’s a complicated history,” he says as he walks me from building to building. “We’re trying to take a new approach to telling it that puts a premium on the experience of people who weren’t Billy the Kid or Pat Garrett.”

Above: Portraits by Maurice Turetsky at the visitor center's gallery. Photograph by John McCauley.

Above: Portraits by Maurice Turetsky at the visitor center's gallery. Photograph by John McCauley.

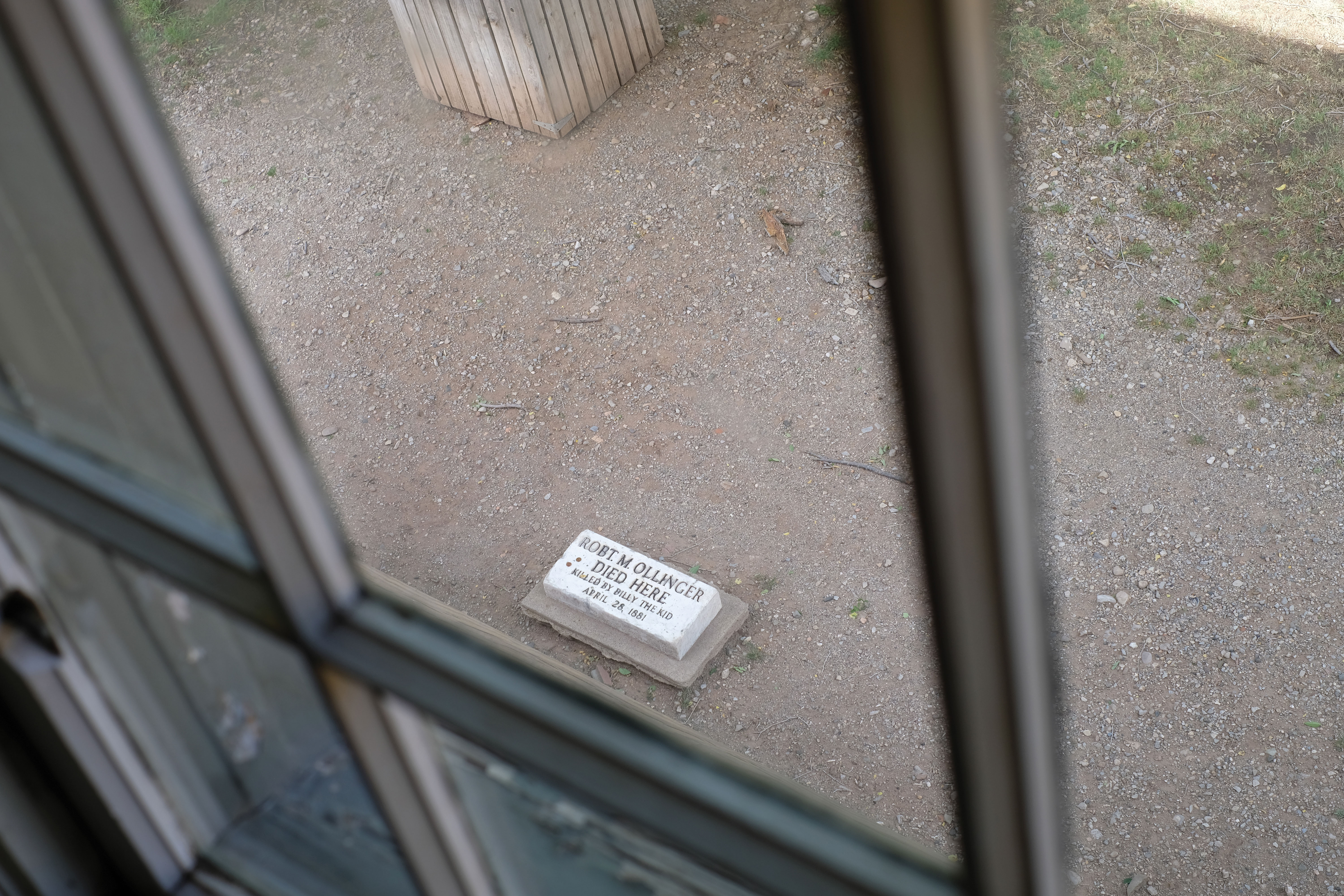

Through that telling, coupled with careful renovations and updates to the exhibits, the site reveals a story of Billy and Pat that’s more nuanced than any I’ve heard before. Roberts and I visit a humbly outfitted bedroom in the old Montaño home, stand quietly inside the San Juan Mission, and finally troop up the stairs of the courthouse. Yes, Roberts confirms, that is the window Billy shot Ollinger from, but he’s more interested in how his team can interpret the breadth of history that happened before and after that—including the town’s role as the seat of Lincoln County government until 1913, when the offices moved to Carrizozo. “We still get people trying to pay speeding tickets here,” he says with a laugh. “Our main goal is this: How do we tie the things that happened in the past to things that are happening today?”

To many, Sheriff Pat Garrett’s killing of Billy marked the end of the Wild West. Change came, people came, and histories—ones just as worth telling as the Kid’s—continued to be made. Late that night, tucked into a brass bed at the Wortley, I hear a gentle rain through the lace curtains of an open window. Slipping onto the porch, I find myself alone with the past as well as the present. I sit in a rocking chair while, beyond me, some 50 townsfolk sleep within century-old walls, waiting for tomorrow.

Read more: Nothing beats summer in New Mexico.

THE NEXT MORNING, Katharine Nelson, who, with her husband, Troy, owns the Wortley, sits with me while I polish off a plate of Hatch green chile sausage, eggs from their backyard hens, and a decadent pastry. She tells me of childhood trips to Lincoln from El Paso with her parents, “and I was so bored.” But when her folks retired to Lincoln, she and Troy grew to love bringing their own little girls for visits from Denver. Eventually they tired of living amid that city’s explosive growth, bought the Wortley, and embraced the easy pace of small-town life. “There was one child in Lincoln,” she says. “We brought two. Tim [Roberts] and his wife brought three. We’re slowly bringing down the median age here.”

Last year, Roberts and two of his pals opened Bonito Valley Brewing in a historic adobe home, a onetime livery stable, because, Roberts says, “I was tired of driving to Ruidoso to have a beer.” The place has become a community gathering place. The evening I drop in, every barstool is claimed, plus most of the tables. Permian Gold, a black IPA, flies off the shelf. Open-mic music tumbles over the picnic tables in a shady yard. “I’d say this is a great side gig,” Roberts says from behind the bar, “but it’s more than that. I really love this town.”

Above: The marker for Robert Ollinger. Photograph by John McCauley.

Above: The marker for Robert Ollinger. Photograph by John McCauley.

Before leaving, I walk down to Annie’s Little Sure Shot coffeehouse and art gallery, where I snuggle into a comfy chair and chat with Annmarie LaMay, who prides herself on the caliber of the artists she represents as well as the joe. “We get a lot of Europeans here, and they say they love the coffee.” As for the “wild” part of the West, she says, Lincoln still has plenty of deer and javelinas.

About 10 miles away, the Hondo Iris Farm sells a broad range of not only irises but other sturdy newcomers to the region—Mexican agaves, primarily—plus native wildflowers that owner/artist Alice Seely and manager Chris Camacho position as a hedge against climate change. The West that was shifting when Billy met his fate now comes with challenges like immigration and catastrophic wildfire. But it also carries beauty—rich brews in a convivial setting, rocking chairs on the Wortley’s creaky-wood porch, the pastel blooms of irises once grown nearby by artist Henriette Wyeth at her San Patricio Ranch.

Read more: No matter your experience level, a hiking adventure awaits in New Mexico.

“People come here to nostalgia-ize the West, but they’re coming with high-tech jobs as well,” Camacho says, referencing Spaceport America, a few hours south. Then he points to a nettle weed that showed up one day and proved its value as a vessel for traditional medicine and food. His assessment of why it gets to stay might as well be Lincoln’s new code of the West: “We like it when volunteers show up,” he says, “as long as they play well with others.”

OUT WEST

Old Lincoln Days, August 2–4, features historic talks and demonstrations, food vendors, crafts, and presentations of “The Last Escape of Billy the Kid.” Plan to stay in Roswell, Ruidoso, Capitán, or a Lincoln National Forest campground.

Lincoln Historic Site’s buildings are open daily. Start with the visitor center’s exhibits.

Snag breakfast with your stay at the Wortley Hotel. The Dolan House has just one Victorian-style lodging, but it also serves breakfast and lunch and has a gift shop.

Annie’s Little Sure Shot offers coffee, pastries, and art Tuesday through Saturday. The Bonito Valley Brewing Company pours beer and wine, along with soft drinks.