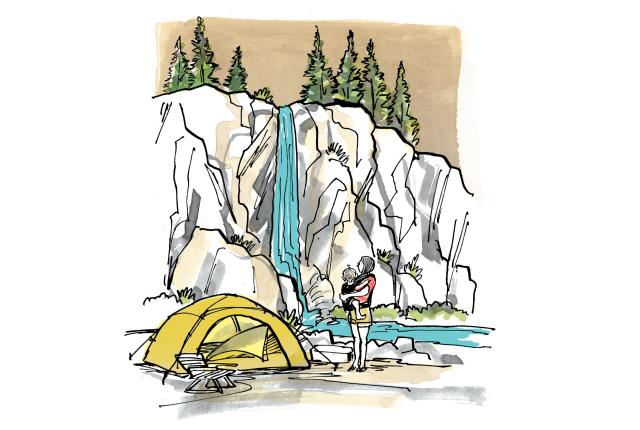

Above: Illustration by Brett Affrunti.

I DREAD SUMMER. Summer is to southern New Mexicans as winter is to Chicagoans: a perfectly legitimate excuse for staying indoors. Daylight saving is on; the evenings grow lighter and longer. Soon I’ll compulsively check the weather for the hour or two just after dawn when the sun can’t yet sear a steak.

What do those of us who live here do when the mercury rockets toward triple digits? Head for higher ground. Summer in southern New Mexico could best be described as an annual search for elevation. On the Gulf Coast, where I grew up, heat lounges in sun and shade without budging one degree. In the desert, heat evaporates in the first sliver of shadow. So we seek refuge in the Gila and Lincoln National Forests, just as pilgrims seek what’s holy.

The forest towns of Silver City, Ruidoso, and Cloudcroft—at elevations ranging from 6,000 to 9,000 feet—offer even higher climbs where we can refresh and recharge. If that sounds like marketing material, you have never felt the sluggishness that sinks into your bones in the southern New Mexico summer, that special lethargy that makes you hanker for hibernation despite it being fantastically sunny outside.

Late summer 2018, nearly 100 degrees. I desperately wanted to head north. But as a newly single mom, I was feeling equal parts nervous and brave at the thought of taking my three-year-old daughter camping on my own. I love the outdoors but don’t collect gear or have solo experience in the wilderness. I wanted to be in the wild with my kid, but I also didn’t want to get in too deep with no cell service and survival skills that top out at knowing how to pack a lunch.

Read more: Alligators—the art of swimming in cool, essential ditchwater.

I called the Forest Service and explained all this to a ranger. He told me Bluff Springs offered a nice combination of scenery, forest access, and people—but not too many—and no RVs. I jotted down the directions in a notebook: Drive 17 miles southeast of Cloudcroft down winding Cox Canyon Highway, then turn west down a gravel lane for the final stretch. It sounded doable.

The next morning, heat clawing at my neck, I loaded my old white 4Runner with amateur-level provisions: a tent and Coleman stove, two sleeping bags, and a cooler. The need to head north was so acute that it burned away any worries I had about camping on our own. We took US 70 over the Organ Mountains, then skirted Alamogordo until White Sands gleamed in the rearview mirror. My daughter slept in her car seat as the road twisted into the Lincoln National Forest.

I turned off the air conditioner and let the air rush in the windows, cooler and cleaner it seemed with every gain in elevation. The truck crawled over gravel on the slow approach into the campsite, and I heard water spattering over rocks. A wet ribbon unfurled over a pine-ridged bluff.

Water always seems a miracle in southern New Mexico. We pitched our yellow tent, loaded it with blankets to soften the ground, topped them with our sleeping bags, tossed in books for me and coloring books and crayons for her. The waterfall—a big word for the spilling stream no more than three feet wide—called to us. It was 20 degrees cooler on the mountain, and the water was freezing.

My daughter yelped and splashed and shivered and jumped in again.

The books never got read. The crayons stayed in their box. We played and hiked and cooked and ate and watched night appear through a window of mesh that was all that separated us from the stars.

In the morning, I made instant coffee. Our tent was perched on a hill, and down below, a gentle creek slid through the grass. I carried my mug. My daughter bounded ahead. With her purple sweatshirt sleeves rolled up, she found her morning’s vocation: making mud pies, dark as chocolate. I took photos of wildflowers.

We had nowhere to be but outside.