EVERY ONE OF ELIZABETH MEDINA'S award-winning pots begins with a mystery. Her mother-in-law, Sofia Medina, a renowned potter, long ago revealed to her an area of especially rich clay, but only after Elizabeth renounced her birthright to Jemez Pueblo. Adopted into Zia Pueblo, her husband’s tribe, she learned the secret place, the sacred stories, the layered meaning of every brushstroke on a piece of art. Among Southwestern tribes, Zia pottery stands apart, as do its potters. The roster of traditional creators includes names like Reyes Ansela Shije Herrera and Trinidad Gachupin Medina, Marcellus’ late great-grandmother. Like them, Elizabeth gathers the special clay and mixes it with handfuls of crushed basalt rocks—the sturdy temper that defines Zia pottery. She coils the toughened clay, smooths it into shape, and applies a white slip, and then she or her husband, Marcellus Medina, paints onto each surface the red, black, and white birds, flowers, and geometric designs that affirm who they are as a people—battered but resilient, with centuries of tradition bound in the muscle memory of their hands.

Fired in a pit, the pots emerge dark with soot. Elizabeth and Marcellus tenderly bathe them, as they would a newborn child. “Sofia taught me that when you create a pottery, you’re giving it life,” Elizabeth says. “It’s like a child you’re bringing up. You give it its first bath and prepare it to be out there.”

Leaving behind her old life and exchanging her Towa language for Keres more than four decades ago wasn’t easy, she says. “But it’s a choice I made to get married to a different pueblo. It’s a tradition we have. If you should marry someone from another pueblo and you’re a woman, you go with that man and take to whatever pueblo he belongs to. I completely left Jemez and accept everything from here. I accept their cultures and beliefs. I am Zia.”

Today she holds Zia traditions so dearly that sometimes, when Marcellus gets too excited about sharing some part of the old stories with other people, she interjects sharply, “Shh. Don’t tell them that.”

Her insistence on holding at least some of their stories safe from others is one part of a lesson the Zias and many other Native peoples have learned the hard way. Time and again, they’ve seen their most sacred symbols and ceremonies turned into public property, often for other people’s entertainment or commercial gain. Here in New Mexico, there is no better emblem for such questions of cultural appropriation than the Zia sun symbol.

When you drive northwest from Bernalillo on US 550, you’ll see a billboard that welcomes you to this sovereign nation, PUEBLO OF ZIA—HOME OF THE ZIA SUN SYMBOL. The circle with sets of four rays adorns the state flag and delivers a shorthand declaration of New Mexico pride. It appears on license plates, the state quarter, T-shirts, coffee mugs, bumper stickers, ashtrays, tattoos, beer cans, portable toilets, and more.

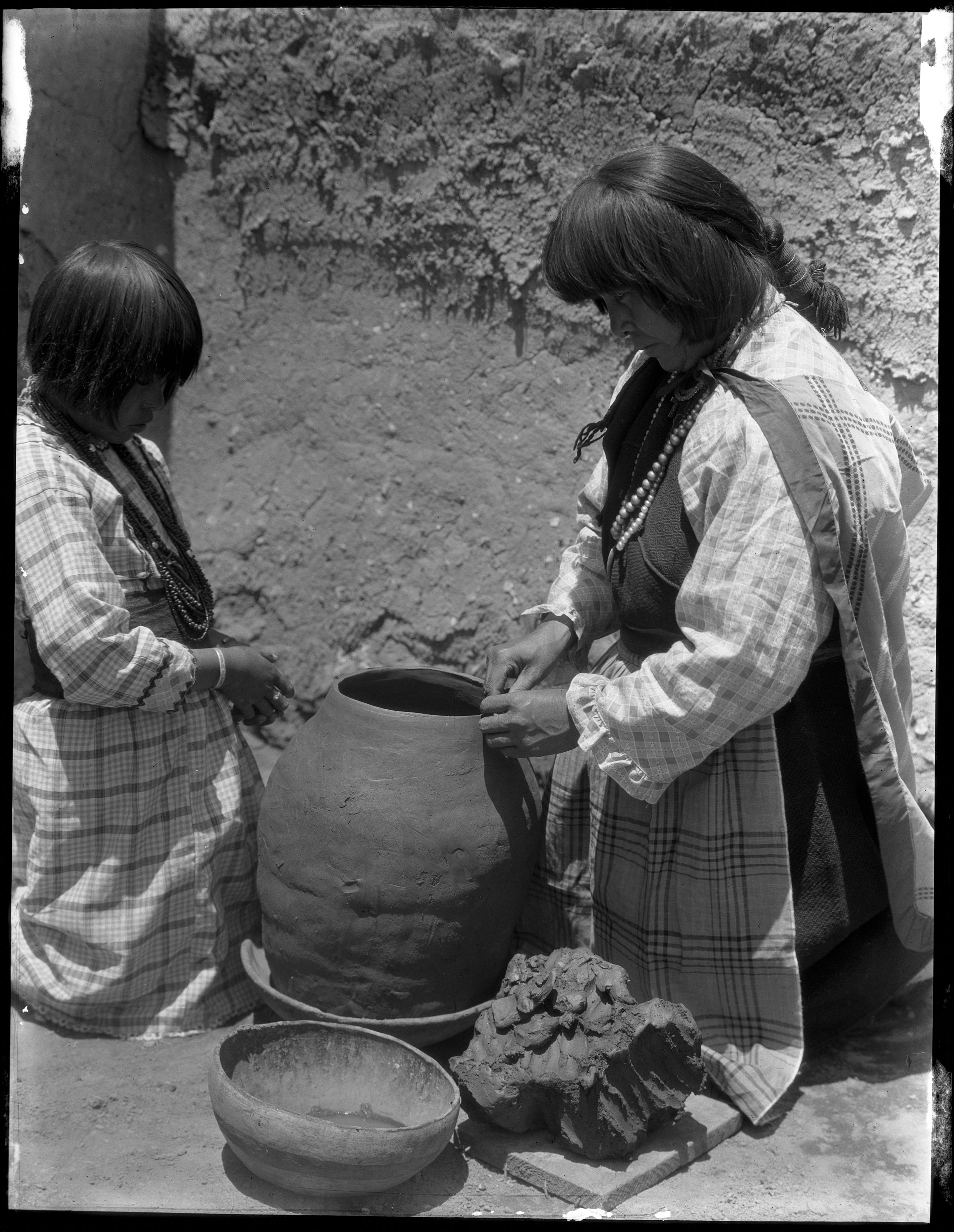

Above: Elizabeth Media shapes a piece of pottery, much as Zia women did in the 1925 Edward S. Curtis image below. Photograph by Steven St. John.

Despite their proud connection to the symbol, Zia people have long decried its widespread portrayals. Adapted from a sacred water jar mysteriously stolen from the pueblo in the late 1800s and returned to its ceremonial kiva in 2000, after years of pleading, the symbol carries all the lessons of life—stories about tribal origins, about family strength, about the interconnectedness of everything on earth. Those stories held together their people after they emerged from Mother Earth and migrated south, eventually reaching Mesa Verde, and, finally, around the year 1200, settling 35 miles northwest of Albuquerque, in the volcanic foothills of the Nacimiento Mountains, where the slender Jemez River peters out. Zia today counts 925 members but once numbered more than 15,000. Decimated first by intratribal clashes, then by the wars and diseases brought by Spanish colonists, and finally by the ravages of 19th-century Americans’ belief in manifest destiny, the people held to their ways—even more so after their membership fell below 100 people in 1890 and one of their most sacred symbols was turned into common property.

In the 1990s, the tribe demanded more than $70 million from the state as compensation for its use—$1 million for every year it had flown from flagpoles. The Pueblo of Zia never filed a lawsuit, but it did win publicity for the symbol’s origin and for the people who carry its name. Since then, lawyers, politicians, and tribal members have continued to seek ways they could protect a treasured part of Zia heritage.

A written statement developed by tribal officials and provided by Zia Governor Anthony Delgarito says: “We are pursuing means of protection through trademarking and intellectual property law at the national and international level. We further intend to pursue some type of legislative or state administrative action. We also hope to have a continual relationship with the state business-trademarking division to require businesses to seek the pueblo’s permission for any trademark application.”

Last year, the pueblo oversaw development of a documentary to push its public education aims and, in other arenas, has seen progress. The tribal council has a voluntary system whereby users seek advice on how they plan to depict the symbol and contribute money to a scholarship fund for Zia children. Among the companies that have done so is Southwest Airlines, which has a plane with the Zia symbol. In 2014, the National Congress of American Indians passed a resolution recognizing the pueblo’s cultural property right to its symbol. That influenced a difficult discussion at Eastern New Mexico University, which ultimately changed its emblem for women’s athletics from the Zia to the greyhound. A few years ago, Bad Suns, a California rock band, used a modified Zia symbol on an album cover. Their own fans blistered it on Facebook. “Shame, SHAME on you,” one wrote. The band eventually sought permission. Just last year, Ho-Chunk tribal members living in Madison, Wisconsin, successfully persuaded city leaders there to remove a black-and-gold Zia symbol from the town’s flag, citing its theft from Zia Pueblo.

Peter Pino, a former Zia governor, helped the tribe initiate the reparation effort, and he knows that hard work lies ahead. “More and more, it seems people feel that the more disrespectful you can be about something, the more money you can make,” he says. “It’s governed by greed: How can I, me, myself use that image to make money for myself? But this dishonors the sun. It’s painful. They’re not showing proper respect. The sun is our father, and he is always watching us. He sees everything.”

BEYOND THE THICK adobe walls of Our Lady of Assumption, arguably the oldest mission church in New Mexico, miles of fallow grid gardens unfurl on hills that roll north toward the mountains. Outlined by volcanic rocks, each plot asserts a once massive tribe’s grandest agricultural achievement. The grids and terraces slowed down and captured rainfall to nourish thousands of acres of corn, squash, and beans. When Spanish colonists demanded every harvest and rationed back meager portions, Zia people turned their basalt-strengthened pottery into giant storage jars that they buried in the ground. There, they hoped to save enough to feed themselves as their population dwindled.

When the first septic tank was dug on the pueblo in the 1950s, Pino remembers, the shovel struck a forgotten pot, spilling centuries-old corn from the watertight clay. “I’m sure there’s still vases buried in the community,” he says. Aboveground, however, a history of poverty and violence left its scars. At one time, Zia’s eroded population underscored the 19th-century notion of the “vanishing Indian,” a part of manifest destiny’s goal to modernize the West. Across our nation and the globe, armies of archaeologists and adventure seekers swept through a host of cultures they considered exotic, bringing home evidence of people they were certain would soon blend into Anglo civilization or disappear altogether. East Coast museums, along with their European counterparts, collected artifacts from Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, and Africa, as well as American Indian tribes.

Above: Zia women shaping pottery.

Ethnologists James and Matilda Stevenson did their part to corrode Zia culture. In 1890, working for the Smithsonian Institution, they came to the pueblo, where they counted 97 people. Fearing its imminent demise, they collected everything they could, including artifacts that have never graced the pueblo since. Sometime after Matilda, then a widow, left the pueblo, a sacred pot from the tribe’s Fire Society disappeared. To this day, no one knows how the pot moved from its kiva to Santa Fe, where it ended up in artist Andrew Dasburg’s home and later the School of American Research (today’s School for Advanced Research), which was then housed at the Palace of the Governors.

The Fire Society pot bore a Zia symbol—a round sun with stylized eyes and a mouth, surrounded by groups of three rays in each of the four directions. In 1923, when the Daughters of the American Revolution announced a contest for a state-flag design, physician Harry Mera recalled the symbol. He and his wife, Reba, worked up a sample that split the three rays into four (unwittingly mimicking a “brother” to the sacred design) and depicted it in burgundy on a golden field to honor the state’s Spanish heritage.

Perhaps Mera felt he was paying homage to Native people, but he didn’t ask the Zias for permission. At the time, they weren’t considered citizens and weren’t allowed to vote. No one on the pueblo could read or write English, instead relying on vast oral histories to archive their knowledge. If they took offense at the flag, they were unable to hire a lawyer. In 1925, Mera won the contest’s $25 prize, and the Zia sign took root. Soon, schoolchildren faced the state flag every morning, hand over heart, and intoned, “I salute the flag of the state of New Mexico and the Zia symbol of perfect friendship among united cultures.” In 2013, USA Today readers voted it their favorite state flag.

In official publications, the state explains the sun sign as representing the four directions (starting at the north and moving counter-clockwise to the west, south, and east), four seasons (starting with spring, then summer, fall, and winter), four times of day (morning, noon, evening, night), four stages of life (childhood, youth, middle age, and old age), and an overall obligation to develop a strong body, clear mind, pure spirit, and devotion to the welfare of others above oneself.

When Pino talks about the symbol, he starts with the circle itself, a geometric figure that neither begins nor ends. Father Sun, he says, greeted his people when they emerged from the three lower levels within Mother Earth to this one, the fourth. To this day, a midwife carries every newborn outdoors to witness his or her first sunrise. Together, Father Sun and Mother Earth make Zia lives possible, providing food for bodies, clay for the pottery to cook it in, and sun-dried bricks for their homes.

When the tribe finally pulled together the resources to question the symbol’s use, it got stuck in a mesh of U.S. copyright and trademark laws that, combined with the passage of time, left their symbol in the public domain. The Zias weren’t alone. Pick any place on the map and you’ll find towns, businesses, and sports teams bearing tribal names. Pontiac, Michigan. Jeep Cherokee. Mohawk Carpets. Chicago Blackhawks. At one point, a task force created by then-Governor Bill Richardson attempted to address the Zia issue by urging construction of a business park on tribal land. At the time, tribal casinos were on the rise, but Zia had resisted that option—as it then resisted the task force’s proposed placement for the development. Zia has recently placed a 10-year moratorium on oil and gas leases due to the dangers of fracking. Many tribal members leave the pueblo for outside jobs, supplemented by family farm plots, a few head of cattle, and the collective kindness of their neighbors.

Above: Zia elder Peter Pino. Photograph by Steven St. John.

Above: Zia elder Peter Pino. Photograph by Steven St. John.

“In the past,” Pino says, “the yardstick of success was: How well are you maintaining culture, language, song, and dance? Now it’s changed in the larger world. It’s the bottom line: How much money do you have? We don’t have a casino, and the leadership doesn’t want it. It changes people forever. We’re carrying on the teachings of our forefathers, who were hunters, gatherers, and farmers. Younger people may disagree, but if we’re going to be who we are until the end of time, that’s what we have to do.”

Pino believes so strongly in those down-to-earth ways that he shares information about them with schoolchildren and during workshops he leads at Mesa Verde National Park. He’s even broadcast them on television. In 2012, he showed Bizarre Foods America host Andrew Zimmern how to hunt for prairie dog, clean it, and cook it over a campfire. “It’s those ways of our people that are going to be the way we survive as the world changes,” he says. “I think about these recent hurricanes and tornadoes. If we were to survive one at Zia, we can go fishing. We can harvest small birds and game. We can live off the land.”

Most important, he says, his people have the company of others who were raised to value “us and we”—the community—above “I, me, mine.” “In the mainstream world,” he says, “a personal battle is often you on your own. But you need help. Here, it’s always us and we. Losing a child or a wife or a husband—those may seem overwhelming. As a community, we help one another. We take a ristra of the chile we grew, some chicos, some meat, and share it with that family. There’s always encouragement.”

Under that philosophy, the many unauthorized uses of the Zia symbol become particularly hurtful. “On plumbing trucks,” Marcellus Medina says, “that’s a disgrace.” He and Elizabeth use the Zia on their pottery, even as other Zia potters resist doing so, as the pueblo leadership prefers. But, Marcellus notes, the couple never uses the three-ray version, nor the eyes or the mouth. “It goes against all our teaching, our philosophy, our culture. You’ll get chased out from this tribe.”

STATE SENATOR MICHAEL PADILLA has pursued a variety of legislative cures to the Zia symbol’s ownership, mainly through memorials that prompted studies of the issue but carried no force of law. “As it stands,” he says, “there’s no way to protect it legally. But the Zia people, they’re not burning the building down and protesting. They simply want to protect the image. Their approach is peaceful.”

Once he got involved, he started noticing the symbol everywhere. And he took personal action that he hopes others will emulate. “If it’s in the bottom of an ashtray, I literally go to the store owner and say, ‘You need to take that off the shelf. Ask the maker to put the symbol on the side or not at all.’ The more attention we bring to it, the more people will start to change.” Go ahead and wear a Zia T-shirt with pride, he says, but think twice if it represents the symbol in a derogatory way. On the political front, Padilla says, he refuses to use it on any of his campaign materials, because the sacred-secular mix doesn’t work for him.

Last year, Padilla spoke on a panel with Pino at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, in Albuquerque, where Assistant State Historian Rob Martinez joined them in the call for granting the symbol more respect. Martinez acknowledged that the sign has evolved into general usage and that even he hadn’t fully grasped its significance. Unlimited use of any symbol, he said, robs it of its meaning. “Kachinas and santos take on iconographic significance for Native and Hispanic people. They’re not just works of art; they’re the word of God in image. Maybe these symbols aren’t ours to use however we want. We do have a free society with free expression, but we can’t lose our sense of manners and respect. Do we want to lose the meaning of all our symbols?”

For the Medinas, choosing to paint the Zia on their pottery demands the level of consideration others would give to depicting the Virgin Mary or the Star of David. Every year, the couple makes the pottery awarded to the college football team that wins the New Mexico Bowl. It has a Zia on it, as does the coffee mug that Elizabeth designed for the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center’s gift shop. It appears on the Zia tribe’s own flag, on the mission church’s doors, and on the front of the tribal administration office—although the building’s designers originally gave it three rays until the elders pressed them to change it to four. No one in the pueblo wants to ban it altogether. But the contributions they seek for its use will go to good ends.

Above: Curator Betty Toulouse (right) holds sacred zia pot that inspired Reba Mera's (left) state flag design, c. 1940-50.

Above: Curator Betty Toulouse (right) holds sacred zia pot that inspired Reba Mera's (left) state flag design, c. 1940-50.

“We’re going to use it for us, for we,” Pino says. “It’s going to educate our people to become attorneys and doctors to deal with the mainstream culture at their level.” Outside the church, pottery sherds pepper the ground. When he was a boy, Marcellus saw one with a bird on it. Taking the sherd was forbidden, so he memorized the bird and drew it in his sketchbook, and today he occasionally includes it in one of his designs, where it takes on traditional meanings. Even colors matter. On the Zia sign, he says, the white rays remind people to stay on the road that is good and true.

“So many things were taken from us,” he says, referencing stories, traditions, and pieces of pottery. Just as Zia’s potters helped keep their people alive during tough times by selling the work of their hands, every new bowl crafted by the Medinas and all the other remarkable potters here holds a line against what was taken, ensuring that the Zia people remain true to Zia ways. That’s one reason why Marcellus is so proud of the pottery Elizabeth produces—pieces finer, he says, than those of Trinidad Medina, whose work collectors covet. Elizabeth humbly disagrees with his assessment but firmly believes that one of her purposes in life is to walk the white road of the Zia way.

“They adopted me and gave me the rights of any other person born here,” she says. “I adopted their culture and respect everything the women do here—the way of the pottery making and how they help me. I create my pottery from my heart, knowing that they welcomed me from their hearts.”

EXPERIENCE ZIA CULTURE

The public is welcome to the annual Pueblo of Zia Feast Day in August. The celebration, which includes singers, drummers, and dancers, moves at its own pace, but it is generally well under way by noon. As with all tribal events, leave your camera in the car and behave as you would at any religious ceremony. If a pueblo member invites you to eat in their home, accept with gratitude—pueblo feasts are legendary. Adding some bread or a dessert to the table is a gracious gesture.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

We’d like to know what you think about the Zia sun symbol and how it should be used or not used. Write to us at letters@nmmagazine.com or New Mexico Magazine, 495 Old Santa Fe Trail, Santa Fe, NM 87501.