Adapted from the book The Work of Art: Folk Artists in the 21st Century

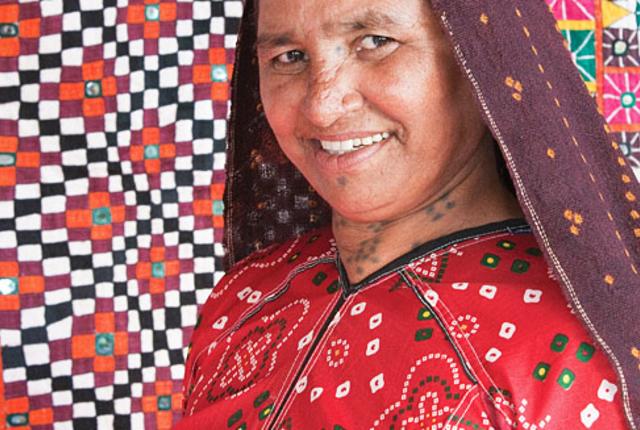

In the summer of 2010, Jamuben Khengabhai Ayar boarded a plane in India and took a brave step into the unknown. A representative of the Trade Facilitation Centre of the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), the commercial arm of a grassroots cooperative of more than 15,000 self-employed women embroiderers from the Indian state of Gujarat, Ayar could not read, and had never traveled to Mumbai or Delhi by herself. Now the Hindu artist was making her way across the world—with four flight changes—alone.

Her destination: Santa Fe, New Mexico, a historic crossroads of international culture and commerce, where she and other SEWA artists would participate in the International Folk Art Market, a grand open-air marketplace in which hundreds of traditional art masters show and sell their work during a two-day honoring of world art and culture. The event would change many of their lives—if they could get there.

Ayar hadn’t planned on going. But when a family member of another SEWA artist died, and Market organizers accepted Ayar as her replacement, the opportunity was too great to reject. The enormity of the journey, however, was overwhelming. Ayar needed a U.S. visa, and while one was quickly granted, the U.S. consulate was closed until after other SEWA artists were scheduled to depart. Remembering an old Hindu saying, she wondered if the venture had “bad or wrong stars,” and if this was a sign. As SEWA leader Reema Nanavaty later detailed, in a letter written on Ayar’s behalf:

On one hand was the livelihood of more than 15,000 sisters, and on the other hand, of Jamuben taking the risk of traveling all alone. But Jamuben was confident, saying, “My sisters and my organization are with me, together with God. If I am confident, others will definitely support.” Jamuben took the Air India flight to Newark. On landing, she followed the rest of the passengers. At the immigration desk, she showed the paper. On realizing that Jamuben cannot converse in English, the immigration official called for a facilitator who was conversant in Hindi and Gujarati. This officer filled up the immigration form. The immigration officer asked her the purpose of her visit. Jamuben responded, “I am going to Santa Fe to demonstrate our skills and explore the possibility of generating livelihood opportunity for my sisters. Our lives depend on our skill.”

From Newark, Ayar flew to Houston, where a thunderstorm canceled her flight to Albuquerque. As she waited, she met a Malaysian artist also traveling to the Market. Ayar finally made it to Santa Fe at 3 a.m., after two days of travel. She had a new friend and newfound confidence. She had the stars on her side as she represented her country and culture at the Market with her handmade art.

Metaphorically and practically, the first International Folk Art Market, held in Santa Fe, New Mexico, on July 17 and 18, 2004, was a bold but blind shot in the dark.

Bold was the Market’s proposition that culture and commerce could coexist in unprecedented ways—in this case, through an ambitious plan to convene the world’s finest folk artists to show and sell the diverse, traditional handmade arts of their communities.

Blind was the Market’s beginning in the shadow of 9/11, when international travel remained precarious and foreign relations were fraught with suspicion.

But Market organizers’ fervent belief that folk art communicates vital cultural and social values lit the way. It overrode political preoccupations and fueled their desire to offer folk artists a respected spot in the global marketplace and to create opportunities for economic, social, and individual empowerment and change. Perhaps most important, it ignited a visionary purpose to compel a world of consumers to buy folk art and to help keep traditional cultures alive.

The big vision: to inspire an international dialogue that elevates master craftsmanship and the art of the traditional handmade above the banality of mass production—to tell the world why folk art matters.

The conversation would be driven by concepts of beauty, community, and tradition, and by big questions of if, and how, a dynamic folk-art marketplace might inspire more consumers to engage in the world in more meaningful ways. If excellence in form, texture, design, and technique were coveted commercial qualities, if 21st-century consumers could find essential value in handmade traditions, could folk art become the socially responsible art of our day? Could an artist-centered international marketplace lead the way in creating more dignified livelihoods and cultural sustainability for folk artists worldwide? Could the enduring spirit and aesthetic splendor of folk art survive?

It was a tall order in tenuous times. Indeed, some critics dismissed the endeavor as idealistic or quaint. The world’s folk artists, however, disagreed. Despite overwhelming obstacles, 61 master artists from 36 countries traveled to Santa Fe to experience what was being billed as the largest international folk-art market in the world. They came from Ecuador, India, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Lithuania, Syria, and Spain. From France, Sweden, South Africa, Mexico, Uzbekistan, the Palestinian territories, and far beyond. They brought exquisite cultural treasures and heartfelt expectations across countless thousands of miles.

In Santa Fe, a community of enthusiastic volunteers imagined and constructed a magnificent global welcome mat: an inviting, color-filled environment where, for 48 hours, all the world would be at home. In this revolutionary global enterprise, only one unknown remained: Would folk art’s promise of beauty, creativity, and cultural diversity inspire the rest of the world to come?

Ten years later, the answer is part of the Market’s founding folklore. The lines began forming at sunrise. They snaked through the parking lot and down the long road to Santa Fe’s Museum Hill that borders the Market site. Organizers had planned for a best-case scenario of 5,000 visitors. Nearly 12,000 stepped under the now-iconic International Folk Art Market sign and into the electric ambiance of an international village.

Ten years later, the answer is part of the Market’s founding folklore. The lines began forming at sunrise. They snaked through the parking lot and down the long road to Santa Fe’s Museum Hill that borders the Market site. Organizers had planned for a best-case scenario of 5,000 visitors. Nearly 12,000 stepped under the now-iconic International Folk Art Market sign and into the electric ambiance of an international village.

As the crowds flooded in, carried along by the curiosity of the unknown and the willingness to open up to something new, an invisible, all-encompassing energy took over. Spectacular handmade artworks shaped through generations of community tradition and change—weavings, clothing, basketry, ceramics, wood carvings, jewelry, metalwork, and more—filled the aisles. Staccato rhythms of Peruvian flutes and African drums merged with the cadences of scores of languages from around the world. Savory smells of exotic foods scented the air.

At the center of it all was a community of artists whose varied ethnicities, clothing, histories, and artistries expressed an astounding range of culture and circumstance. Some artists had never before left their hometowns or villages. Others had endured lives of political and personal hardship. While some lived in war-torn or environmentally devastated countries, others called modern urban centers home. Still others lived in developing countries, where, at the time, according to the World Bank, one in four people strived to survive on less than $1.25 a day.

All made space in their lives to make art.

It was a dizzying multicultural display and a profound human experience. If the visiting artists knew little of one another’s cultures or countries of origin before the gathering, they likely knew less about the eager audience with whom they now shared common ground. With barriers in language, social customs, and business practices, communication could be challenging. Yet with every object admired or sold, intercultural differences gave way to a higher dynamic of diplomacy, sharing, and meaningful exchange. Folk art not only brought these disparate peoples of the world together, it connected them in the most unexpected ways.

For two days on this unique world stage, folk artists were fêted and praised. Every artist made sales, valuable networking contacts, and new friends. Every visitor, from awestruck children to seasoned collectors of folk art and international travelers, learned something new about the world. Even those who viewed one another through the tarnished lenses of government, politics, ethnic conflict, or warfare glimpsed new possibilities for mutual respect and understanding through the bright picture window of folk art.

As a community that has maintained its diverse, deeply rooted traditions in the face of change, and as a centuries-old crossroads of international culture and commerce, Santa Fe was the ideal place to launch the project. Steeped in the longstanding local lore of Native and Hispano peoples, whose own folk-art traditions have been celebrated, with the annual Indian Market and Spanish Market, since the 1920s, the city had long drawn visitors in search of authentic cultural experiences and expressions in art. Furthermore, the city’s large population of fervent collectors was already invested in the beauty of folk art—wearing it, using it, and decorating their homes with it—and understood the reasons for honoring its makers.

A fast-growing circle of Market leaders and friends called on international colleagues, folk-art dealers, and collectors for help in connecting the Market to culture bearers worldwide. No one could yet say what the Market would look like, but they could promise an expertly curated, high-quality exhibition and sales venue where artists would be valued as indispensable cultural assets. Despite the challenges of traveling abroad, the promise was enough for artists and their representatives from around the globe to sign on.

The inaugural Market, like every one since, was painstakingly planned and meticulously executed. Supporting the preparations was an army of 300 volunteers, who drove everything from donor development, marketing, and public relations to artist hospitality, musical entertainment, and site decorations. It took two years of hopeful planning and nerve-racking unknowns. Funding was raised, artist visas and airline tickets were secured, and countless thousands of artworks were crafted, packed, and shipped. Finally, as the sun rose over Museum Hill on the morning of July 17 and the final touches were placed on the global stage, all anyone could do was wait.

In the end, it wasn’t what anyone had planned. It was pure synergy, a rare moment when all the right players and pieces of the world came together in a common vision, united in the values-driven ethic of the traditional handmade.

Nearly 12,000 visitors and close to $1 million in sales. Lives—both of artists and visitors—changed. Artists returned home with earnings to feed their families and to support their communities in meeting vital needs of daily life, and with a new awareness of their value as significant cultural contributors. Veteran and novice lovers of folk art returned home with one-of-a-kind treasures to live with, singular experiences to remember, and venerable cultural values to ponder. Whatever idealism had motivated the Market was now grounded in the reality of an experience that proved that investing in folk artists and their communities in some way transforms everyone who shares in the exchange.

Today, a decade into the life of the International Folk Art Market, the event continues to impress. Since the Market’s founding, 650 artists and organizations from 80 countries have collectively generated more than $16 million from sales at the Market. In 2012 alone, Market sales reached $2.4 million—an average of $18,253 in sales per booth. Participants and their organizations take 90 percent of their Market earnings home to improve the lives of their families and other community members, including more than 100,000 members of artist cooperatives and small family enterprises. By the end of the 10th Market, in July 2013, the event will have touched the lives of more than a million folk artists and others in traditional communities worldwide.

in the 21st Century will be available at the International Folk Art Market, July 12–14, 2013. Hardcover $60, paperback $29.95. Visit folkartmarket.org for a complete list of upcoming author signings and places to buy the book. Distributed by the Museum of New Mexico Press (mnmpress.org), published by International Folk Art Alliance Media.

NEED TO KNOW: Folk Art Market

This month, the International Folk Art Market will celebrate its 10th anniversary by bringing together more than 190 artists from 60 countries for a vast and colorful bazaar on Museum Hill in Santa Fe. Master artists will offer beautiful art that draws on timeless traditions while marketgoers experience the thrill of discovering one-of-a-kind treasures while meeting and supporting the artists who made them.

The Market is held on Milner Plaza, adjacent to the Museum of International Folk Art. Visit folkartmarket.org for tickets, shuttle bus, and parking details.