“I AM HERE," said Zuni Pueblo scholar Edmund J. Ladd. “I am here, now. I have been here always.”

Twenty-five years ago, Ladd’s simple declaration lent itself to Here, Now and Always, an exhibition at Santa Fe’s Museum of Indian Arts & Culture that forever altered the museum system. Created in partnership with Native American communities across the Southwest, Here, Now and Always debuted in 1997 and centered on Indigenous people as the preeminent authorities on their own history and lifeways.

As the permanent exhibition at the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture until 2019, it presented a richer narrative of the Native experience, told by Indigenous voices from all walks of life instead of Anglo curators. Ladd’s words described an exhibit that celebrated Native culture as a living, breathing, quintessential part of the Southwest, uncontained by glass display cases.

On July 2, the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture opens the moving new iteration of Here, Now and Always. (Think of it as HNA: The Next Generation.) More than 20 curators and a Native-owned construction crew have worked to revamp and renew the original show. They’ve gathered fresh perspectives and more than 600 objects from the museum’s collections, updated technology, and reimagined ways to tell Indigenous stories from a 21st-century vantage. The result is an immersive cultural encounter that is every bit as engrossing and inspirational as its precursor.

At the exhibit’s entrance, a moody, blue-lit tunnel of emergence evokes the creation stories of tribes across the region. “It’s a transitory space for the visitor to challenge their expectations,” says Tony Chavarria (Santa Clara Pueblo), the museum’s curator of ethnology. “They’re not here to experience a normal natural history exhibit or an art exhibit.”

From there, Here, Now and Always engages visitors via several themed galleries: Art, Community and Home, Cycles, Language and Song, Trade and Exchange, and Survival and Resilience. Organized in a nonlinear, choose-your-own-adventure style, the art, clothing, jewelry, ceramics, and other objects in the 8,400-square-foot wing are interspersed with video features and walk-in re-creations of a Pueblo house and a trading post.

As with the first exhibition, the sheer array of objects makes it likely visitors will notice something new on each return visit. Wells Mahkee Jr. (Zuni Pueblo), co-chair of the museum’s Indian Advisory Panel, compared the experience to looking into a kaleidoscope. Still, some features stand out. Here are six don’t-miss stories from Here, Now and Always.

Mary Weahkee (Santa Clara Pueblo/Comanche) created this Turkey Feather Blanket with more than 15,000 feathers. Photograph courtesy of the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture.

Mary Weahkee (Santa Clara Pueblo/Comanche) created this Turkey Feather Blanket with more than 15,000 feathers. Photograph courtesy of the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture.

Turkey Feather Blanket, Mary Weahkee (Santa Clara Pueblo/Comanche), 2020

Turkeys came to the Southwest by way of Mexico, from the Aztec people who traded there starting in the 1100s. “One bird yields around 600 feathers,” says the artist. “That cloak alone uses over 15,000 to 16,000 plumes.” An accompanying video demonstrates Weahkee’s painstaking feather-weaving technique.

U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland wore this traditional Pueblo dress during her swearing-in ceremony for the House of Representatives in 2019. Photograph courtesy of U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland's Office.

Dress Worn by U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, circa 2010

Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) wore this traditional Pueblo dress at her swearing-in ceremony for the U.S. House of Representatives in 2019. That year, she made history as one of the first two Indigenous women to serve in Congress; in 2021, she became the first Indigenous person to be part of a presidential cabinet. When Diane Bird (Santo Domingo Pueblo), the museum’s archivist, asked the then-Congresswoman if she would donate her dress to the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture, Haaland got teary-eyed. “I never thought a museum would be interested in my clothing!” she said.

Backpack, Gloves, Shirt, Pants, and Boots, Ramah Navajo Hotshot Crew, circa 1970s

Lola Henio (Ramah Navajo) gifted her protective gear to the museum from her time spent working on an Indigenous firefighting crew half a century ago. “It was hard work, but we did it,” says Henio. Bird says she’s particularly fond of this outfit in the Survival and Resilience section, which speaks to the diversity of professional pursuits by Indigenous people in the Southwest over the past century.

Pueblo House, circa 1944

Bird says the museum’s replica of a 1940s-era home reminds her of her grandmother’s house at Santo Domingo Pueblo. Clean walls whitewashed with gypsum and prominent vigas and latillas shore up the adobe home. An exhibition contributor from Acoma Pueblo walked into the space, Bird says, and simply told her, “This feels so good.” A poem on one wall by Ladd, the former MIAC curator of ethnology, sums up the elements of the Pueblo home: “Made of stone and mud,/the foundation,/the four corners,/Made of earth and wood/the roof,/the center./All anchored with prayers.”

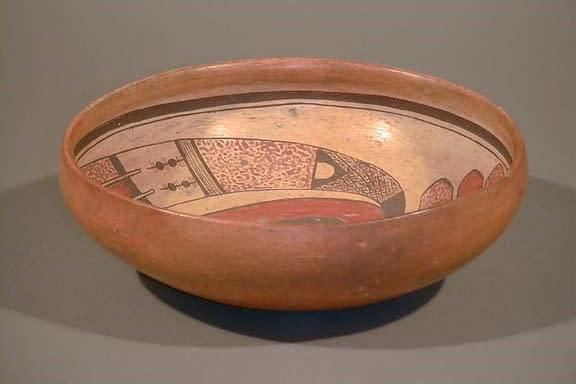

Nampeyo was one of the 20th century's greatest ceramicists. Photograph courtesy of the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture.

Bowl, circa 1910, Nampeyo (Hopi/Tewa), 1859–1942

After Hopi ceramics production waned in the 1700s, Hopi potters relearned the art from Zuni Pueblo artisans in the 19th century. But Nampeyo, one of the 20th century’s greatest ceramicists, was also inspired by sherds from ancient Hopi sites. Her fluid strokes and fine lines decorate this exemplary bowl, made a decade before she went blind. She continued shaping vessels until her death.

Bell Fragments, Undated

The remnants of a destroyed iron Spanish mission bell were found after the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, near a Catholic church at Ogha Pogeh/White Shell Water Place/Santa Fe. Indigenous warriors decimated church implements in more than 40 Pueblo and Hopi villages to express their anger at being forced to practice a foreign religion. “It was a symbol of their oppression,” says Chavarria. “It takes a lot of energy to destroy something so strong.”