On the west side of Mesilla’s storied Plaza, between two unassuming storefronts, is an unremarkable door. But behind this door is a staggeringly rich trove of over 4,000 treasures: a unique collection of art, furnishings, textiles, and ephemera spanning four centuries. In toto, they tell the story of New Mexico and its borderlands. And they tell the story of the collector, J. Paul Taylor, one of Mesilla’s—and the state’s—most notable living treasures. To this day, bold and curious souls who knock on this door often find that Taylor himself opens it with a smile, and offers to show them around.

It’s just something J. Paul Taylor has always done. For the people of Mesilla, the connection between the revered former teacher, legislator, and cultural ambassador and his house is intrinsic. Ten years ago, all of New Mexico stood to benefit when Taylor and his family decided to donate the house and its unique collections to the state.

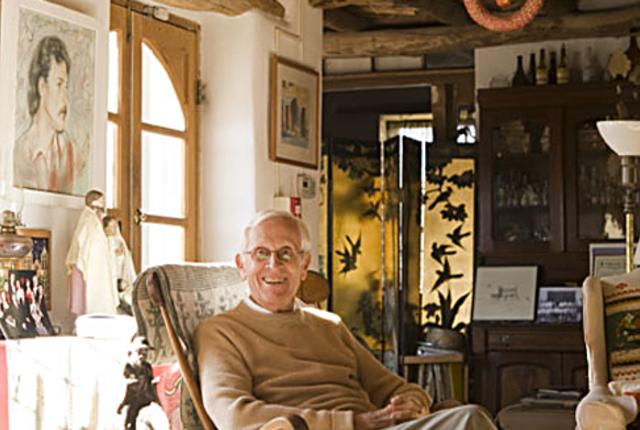

Now 92, Taylor settles easily into a damask-covered chair in the gran sala. Its tables are laden with a lifetime of memories in stone, wood, and paper—a perfect stage on which to talk about his life and the house that holds it.

Mesilla is where Taylor and his wife of 63 years, Mary (who died in 2007), wanted to live from the very beginning. They each had history here. He attended what’s now New Mexico State University, and Mary had visited occasionally, and they both thought it was the right kind of place for raising their family. “Tourists described it as quaint, but we saw a quiet and vibrant Hispanic community filled with wonderful people,” Taylor says, explaining the beginning of a relationship with the village that has grown stronger over the past 66 years.

Taylor began teaching in 1951, and over the course of the next 34 years would introduce bilingual education and new ways of teaching history to the district, in addition to serving as a principal in, and finally as the associate superintendent of, the Las Cruces Public Schools. He speaks with passion about the charter school named for him two years ago, and relishes his time spent with “all those curious kids, who just want a chance to learn.”

“After nearly four decades of teaching, I was looking forward finally to puttering around in the patio and doing some writing,” Taylor says. “It didn’t work.” A year after he retired, in 1985, Taylor was convinced to run for New Mexico’s House of Representatives. He won, and over the next 18 years he represented Mesilla and the surrounding area, becoming known among his colleagues as “the conscience of the Legislature.” He served as the chair of the House Health and Human Services Committee, and was instrumental in establishing the Department of Cultural Affairs, which administers state museums and monuments, and is the agency to which he has entrusted his home and its contents. “It was one of the highlights of my time in the House,” he says of the DCA. “It ensures that what is unique about New Mexico and this area is preserved and taught—that there is a bridge between the past and the present.”

The past is important to Taylor—part of his makeup. “We’re an old New Mexico family,” he says, noting that his mother’s side goes back to Francisco Vásquez de Coronado y Luján’s expedition in 1540, and that his family was part of one the first waves of settlement. Various generations of forebears—many of whose portraits hang throughout the house—include the founder of the New Mexico Republican Party, Civil War veterans, a commander of the Santa Fe garrison, representatives to various government bodies, and ranchers. “After all that, we ended up on the farm in Chamberino, where I was born.”

Following university, and a time in the Navy during World War II, Taylor married his childhood sweetheart, Mary Daniels, in 1945. She and Taylor slowly modified the house to accommodate their growing family. By 1958, they had seven children; four still live in Mesilla today. Mary encouraged the first tours of the house.

With kids at home and kids at work, Taylor’s reputation as a teacher and storyteller grew. Almost from the beginning, he says, he “wanted to teach New Mexican history differently. I wanted my students to see and touch their history. To understand the connection between their lives now and their past.” The house presented an ideal opportunity.

With the house already beginning to fill with his and Mary’s art collection, Taylor turned it into a very different sort of classroom. “Coming to the house helps some kids value their own culture and their own experiences, and helps their friends, who might not share that culture, understand it better.”

One of the best teaching aids—what Taylor calls “learning things”—is the portrait collection, which includes images of Taylor’s great-grandparents Miguel Romero y Baca and Josefa Delgado de Romero, who lived in the mid-19th century, and continues through his own children to his grandchildren. “The portraits are a big hit, “Taylor remarks. “The kids—well, almost everybody, in fact—always want to know about them. They tell stories about family and history. We can look at them and ask questions about how people dressed and what that might mean.”

But it’s not just students who flock to the house and what it has to offer to increase understanding of southern New Mexico and the borderlands. For many years, incoming presidents of New Mexico State University and members of the New Mexico Museum Board of Regents would come to the Taylors’ house to spend time talking and get a crash course in regional lore.

“We look at things like the santos and the bultos, and the furniture. We talk about what they mean, and what their place was—and is—in the history and culture of the area.”

Then there are the folks who just stop by to see what’s behind the walls—the purely curious, of whom there are many. Taylor is amenable. His habit of taking folks on impromptu tours, his sort of reflexive hospitality, is multigenerational.

“I’d finally convinced my mother [Maria Margarita Romero de Taylor]—at 90 or so years old—to move off the farm and into the house,” says Taylor. “Her apartment opened onto the Plaza, and one day I walked by and noticed that she and a woman I’d never seen before were having tea and bizcochitos, and laughing like old friends. Later I asked her who the woman was, and she said she had no idea, just a nice lady who wandered by.”

Taylor and his family’s lifelong affinity for the borderlands region is evident in each of the house’s 13 rooms, and in the bones and body of the structure itself. Built, rebuilt, remodeled, and renovated over 130 years, the house tells the story of different cultures and times coming into contact and becoming something new: It’s a microcosm of the American experiment, but its easy movement from inside to out, its thick adobe walls—and, of course, the artwork—give it a distinctly Southwestern feel.

This not lost on Taylor; he’s worked hard to refine and burnish it. “The house is as much about my family as it is Mary’s, as it is about the Barelas of the 1880s, and the Reynoldses of the first decade of 1900s.” And indeed, Taylor and his wife insisted that the monument name encompass those family names as well as their own: the Taylor-Barela-Reynolds-Mesilla State Monument.

“The house is really about telling the story of what an authentic Hispanic house of a certain sort would look like,” says Taylor. A large part of the collection is religious in nature, and includes his first real art purchase, a 19th-century statue of Santiago de Compostela that he purchased on a five-dollar layaway plan in 1956. To it has been added a wide assortment of bultos, ceramics, and retablos. “I don’t want people to think I’m evangelizing. But this is real; this is the way houses like this were.” But, after a moment of reflection, he adds, the collector’s glint in his eye, “It might be a little over the top.”

The many bookshelves throughout the house contain late 17th-century Spanish works as well as more contemporary titles. Textiles, both newly collected from Central and South America, as well as quilts—some of appliqué silk—made by his mother, and Hopi and Navajo blankets can be found on beds and stacked on chests. Paintings and sketches by artists such as José Cisneros and family friend Ken Barrick line the walls. Notable too are the fruits of Mary’s many years as a photographer.

Furniture spanning at least four identifiable periods and styles (French salon, Victorian, Neoclassical, and early Hispanic) is scattered throughout the house. Taylor is also an avid collector of folk art. “The things I love are humble things, made by humble people,” he says. Indeed, while there are elements of what might be considered high culture throughout the house, it’s things like a favored rough-hewn chair in the gran sala, pots from New Mexico pueblos, and a brightly painted bullfighting diorama—products of people simply living their lives, expressing their faith, and embracing beauty—that most resonate.

But for all of this, Taylor’s house is more than a classroom or a museum. It was, first and foremost, his family’s home. And to mold it to their needs, they added to the original structures while keeping an eye on the history and overall character of the house.

“The current house was originally two storefronts with residential quarters behind, and once we’d bought both of them, we had some practical problems,” Taylor says. “We’d have to go outside to get from one side of the house to another. So we enclosed a section of the patio between the two, and created the gran sala.” The other notable addition was one that has taken on greater significance as the cycles of life have made themselves felt in the family, first with the death of Taylor’s son John, in 2004, and then, three years later, that of Mary. At the same time they built the gran sala, the Taylors built an oratorio (a chapel, a traditional component in many Hispanic homes). It now holds images of the Virgin Mary, the chalice used during John’s wedding and funeral, the rosary used at Mary’s funeral, and the ashes of both loved ones.

Inevitably, the losses of Mary and John are among the most potent of memories for Taylor. But he is a man long used to that pain, and smiles broadly when he thinks back. He sees much that he loves. Topping that list, he says, is the house as a place that hosted and still hosts “great gatherings of family and friends around the table on Sundays and holidays, gatherings that have gotten so large that they now overflow. Times of joy.”

Taylor sees the house and his gift of it to the state as a chance to preserve a way of life. “There is nothing else like this. I hope people 50 years from now can come here and get an idea of the passage of time, and how people lived, and understand that the things in the house reflect what they found important.” Others agree. A few years ago, a group of local citizens got together and formed the Friends of the Taylor Family Monument. Today they help Taylor and his family prepare the house for its eventual transition to state management, run special tours, and raise funds.

“J. Paul is one of the most precious and special people I’ve ever met,” says Veronica Gonzales, the state’s Secretary of Cultural Affairs. “He’s dedicated his life to the people of New Mexico, and the very essence of him is in that house. And that house,” she says adamantly, “is who we really are. It’s our story.”

Back in the gran sala, after two days of conversation, Taylor answers a question about what has changed in Mesilla—the little village he and Mary moved to with such joy and hope nearly 60 years ago. “What strikes me most,” he says, a little bemused, “is just how busy everything is now.” The light from a photographer’s flash momentarily illuminates the room in front of him; a grandchild comes in from the back patio, hugs him; a member of the Friends group pauses to ask a question. Taylor’s desire to be “puttering around in the patio and doing some writing” has been subsumed—gladly, it appears—once again by the pleasant industry of his house and what it will become.

Need to Know

The Taylor-Barela-Reynolds-Mesilla State Monument is not yet open to the general public. Special tours and school trips can be arranged through the Friends of the Taylor Family Monument. (575) 915-5756; ftfm.mesilla.nm@gmail.com; ftfm-mesilla-nm.org

Peter BG Shoemaker is a New Mexico writer and journalist. Chris Corrie is a Santa Fe-based photographer. See more of his work at santafestockphotos.com.