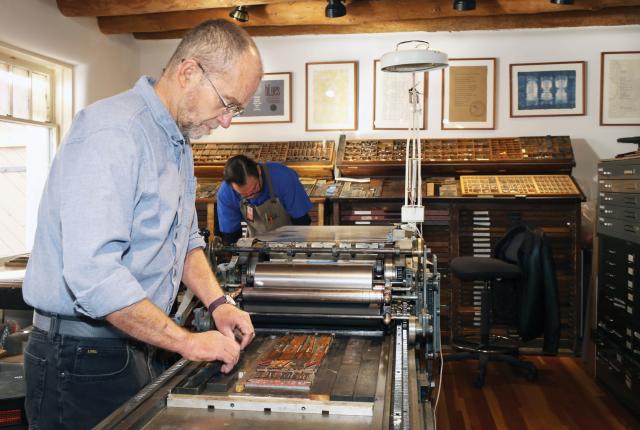

Above: Thomas Leech (left) and James Bourland prep the Vandercook. Photographs by Allison Pharmakis.

Thomas Leech stands at the belly of a 65-year-old Vandercook letterpress, a hand-operated, half-ton beast of a machine that’s about the size of a James Bond–era sports car. The director of the Palace Press at the New Mexico History Museum, in Santa Fe, Leech might as well be Yoda, with his round eyeglasses and Zenlike demeanor—and he is about to conjure magic. Metal grippers anchor a sheet of paper to a heavy-impression cylinder as he turns a crank on the machine, unleashing first a set of inked rollers across a square of metal type, then the paper, the mechanical glissade finishing with a satisfying clank.

Gently, he pulls away the paper, revealing a poet’s words embedded with a whisper. “Whenever we print for kids here,” he says, “they have this aha moment. One moment this isn’t there, and then it is.”

That piece of slow-ink printing represents centuries-old technology still practiced with painstaking precision. Leech takes days, sometimes weeks, to meticulously set the type, boost the height of letters that have worn thin, and add hair’s-width spaces with blank pieces of lead. He spends weeks, sometimes months, finding just the right kind of paper, even crafting it himself. He invests months, sometimes years, in mulling over ways to bring someone else’s words to life via letterpress.

This year, the Palace Press hits its 50th year of book-arts craftsmanship, with plans for long-awaited publications and an unprecedented bounty of tools to carry them out. Surrounding Leech in this long, narrow, adobe-walled space that once served as stables for the Palace of the Governors are 11 antique presses—or maybe 15; he’s sort of lost count—along with 500 cases of wood and metal type, more than 5,000 wood, linoleum, copper, and zinc engravings, inkpots, paper cutters, saddle clippers, sewing frames, and tools for decorating leather bookbindings. In one corner, he’s re-created the print studio of famed Santa Fe–based artist Gustave Baumann, with the ca. 1900 press, powdered inks, and tools once used by the master in his backyard studio off Old Santa Fe Trail. The joint is one part museum exhibit, one part working press. Among the DIY makers of cheese, beer, and even salad greens who have achieved artisanal small-batch status, Leech and the Palace Press have become stars in a national letterpress renaissance that claims satellites throughout New Mexico.

Above: Fonts are ready for printing on the Vandercook press.

Power & Light Press, in Silver City, inks up sassy NSFW greeting cards with an all-female press crew and an annual Print Fiesta where a steamroller stamps giant prints. In a renovated brick-and-adobe hardware store in tiny Magdalena, Laurie Taylor Gregg and Glenn Bigelow’s Village Press Print Studio combines letterpress with fine-art lithography and a coffee shop dubbed “Es-press-o.” At Madrid’s Wildland Press, Blossom Merz prints custom orders using inks he made from pulverized rocks gathered on nearby hikes. In Santa Fe, a variety of makers have latched on to heavyweight, hand-powered machines to produce wedding announcements, political posters, and one-of-a-kind cards.

“It’s a very attractive art form,” Leech says. “But it takes a lifetime to learn this stuff. There’s a yin-yang between paper and print. You see more paper than print, so even that makes a comment. The printer’s job is to be subtly expressive, to support the message and enhance the mood. The beauty comes from the sensitive handling of the materials. It’s how it feels in your hand, the sound of it, even the smell. It’s sensual.”

Despite those positives, Leech regularly dissuades people from taking up a craft that has grown into a craze. “It’s like adopting a teenager: There are problems that come with it. And you have to be using it. Printing is a verb. If you’re not using it, it’s an 800-pound dust catcher.”

The Palace presses get plenty of work. Along with fellow pressman James Bourland, Leech has amassed an array of poetry broadsides (the literary equivalent of posters) and limited-edition, hand-stitched books that can cost hundreds of dollars and weaken the knees of serious collectors. Leech’s first project upon taking the helm in 2001 was a broadside collection of revered poets like Naomi Shihab Nye, John Brandi, and former U.S. Poet Laureate Rita Dove. Brooklyn-based, New Mexico–born poet Gary Mex Glazner, who’s won global accolades for his Alzheimer’s Poetry Project, brought him the idea and helped dream up printerly approaches. For one, Leech crafted paper that included holy dirt from the Santuario de Chimayó. Another used bits of a 1930s road map of Route 66. And he experimented with blending a poet’s words and his own marbled paper—a riff on an ancient Islamic technique that he’s since turned into an art form of his own.

Above: Blossom Merz grinds rocks into powders that he uses for pigments at

Wildland Press.

Margaret Wood’s memoir of Georgia O’Keeffe, Remembering Miss O’Keeffe, includes the print of a deeply evocative engraving of the artist that the press commissioned from celebrated Tennessee illustrator Barry Moser. Leech’s version of Jack Thorp’s Songs of the Cowboys represents a labor of love—and legacy. The original Songs of the Cowboys, the world’s first collection of round-the-campfire songs by real-life New Mexico cowboys, was printed in 1908 in Estancia, on a Chandler & Price press now owned by the Palace. (It’s the same 112-year-old, foot-treadled gem that visitors to the museum’s annual Christmas at the Palace use to print holiday cards.) Leech’s version of Thorp’s book incorporates grama grass into the paper; artist Ron Kil hand-colored every illustration in the 10-book deluxe set.

For such work, Leech has won a Santa Fe Mayor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts and a national Carl Hertzog Award for Excellence in Book Design. It’s a far cry from the Grand Rapids, Michigan, kid who took a junior high semester of printing and walked out of it with this prayer: “Please, God, don’t let me be a printer.” Years later, living in Colorado Springs with his young family, Leech set aside his art degree in painting and sculpting and took a job with an offset-printing company. In his spare time, he started playing around with papermaking, then met a guy who had a Chandler & Price letterpress in his garage. They made some business cards, and Leech offered to buy it, then and there. The guy said no way, but a few weeks later he called Leech and said that his wife really wanted it out of the garage. “Best $500 investment I ever made,” Leech says of the machine, which today could command four or five times that.

Other press adherents tell similar stories of acquiring their equipment. Kyle Durrie, founder of Power & Light Press, exults about her Golding Official No. 3, two Heidelberg Windmills, and two Chandler & Prices, as well as her Challenge proofing press. But, she warns, “the first press I ever got took five years to fix. When you’re plugged in, they appear every now and then. A friend of mine found a barnload of equipment in Nebraska.” Gregg gushes about her preference for wood type over metal, because, for her, “it has history in all the nooks, nicks, scratching, and wearing. I know they’ve been well loved.”

Merz left southern Oregon last fall for Madrid—where startup artists can afford rent and find local support, he says—but as 2018 turned to 2019, he was still raising cash to move his Chandler & Price to his Wildland Press storefront. In the meantime, he’s making do with a World War II–era tabletop Craftsmen Imperial and borrowing time on larger presses from Liza Bambenek’s Penumbra Letterpress, in Santa Fe. A reliable seller: sets of delicately hued ink powders and watercolor paints that he makes from rocks. “My primary art is hiking,” he says. “All these colors are the memory of a place and an experience.” Learning of Leech’s penchant for making papers that likewise carry products of the earth, Merz freezes in place, then whispers, almost reverentially, “There’s so much to talk to Tom Leech about.”

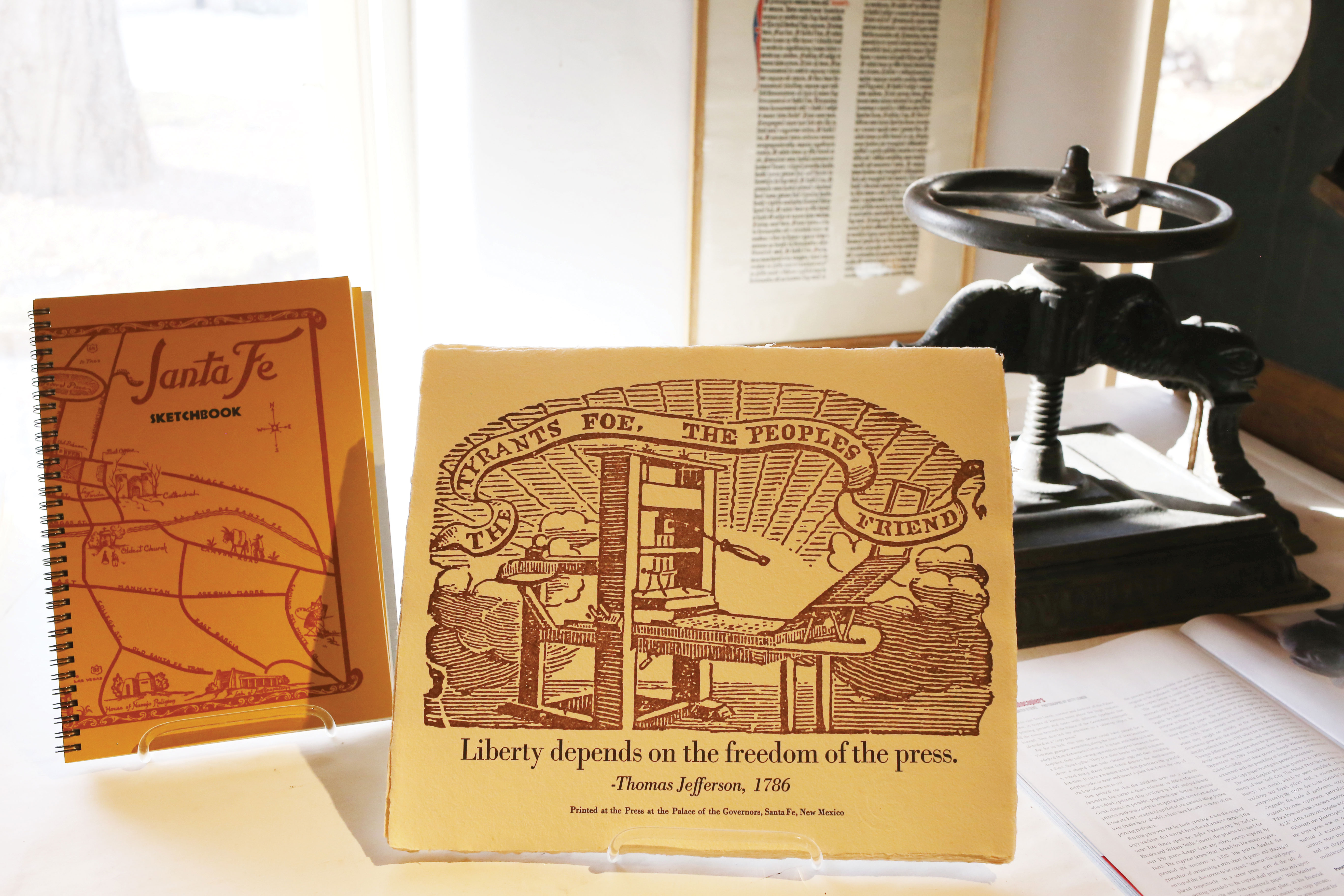

Above: A sample of Palace Press productions.

James Bourland entices a new generation of presspeople through his classes at Santa Fe Community College. “Letterpress is exotic,” he says. “The students are looking for something tactile, Old World, and heavy impression—which I frown upon.” He’s referring to debossing, or leaving deep indentations on the paper, which many enthusiasts adore. Printing purists, however, say the paper should barely “kiss” the type, to slow down its inevitable wear. But latter-day innovations in easily reproduced photo-polymer plates sweep aside the need for wood or metal type—and expand the grasp of letterpress wannabes.

Still, Bourland says, history matters. “This kind of printing goes back 500 years. It allowed mankind to crawl out of the Dark Ages. It is a noble profession. I tell the students, ‘I don’t take myself seriously, but I do take printing seriously.’”

In coming months, Leech plans to tackle some of the most serious challenges of his printing and curatorial career. He’s one of 26 international printers paired with writers like Margaret Atwood, Wendell Berry, and Joy Harjo for Extraction: Art on the Edge of the Abyss, a portfolio by the Berkeley-based Codex Foundation. Leech is paired with Santa Fe’s first poet laureate and Guggenheim Fellow Arthur Sze; starting price for the 50 portfolios is $3,000. He’s writing an essay for the first catalogue raisonné of Baumann’s art, to be published by Rizzoli New York this fall. And he’ll be the first printer ever to ink woodblocks carved by Baumann since his 1971 death. The prints will illustrate a never-before-published book about saints written by the late Mary Austin.

“It’s a big deal that we have the Baumann estate’s permission to do this, but also that we have their moral support,” he says. “I don’t go into this lightly. I have so much respect for Gustave Baumann and his work. He was always experimenting. He never did things the same way. He wasn’t cranking things out by formula.”

Not coincidentally, Leech doesn’t do things by formula, either. From accordion books to slyly subversive posters to handmade papers to back-and-forth collaborations with authors, he stands today as The Guy to whom authors and printers turn for help.

“Tom’s work gives a place for poems to live,” Glazner says. “He’s the perfect partner for anyone who loves words and language.” Even better, Glazner says, is to catch him at work. “You should see him dance as he cranks the old press.”

GET SOME GOOD PRESS

The Palace Press at the New Mexico History Museum is open 10 a.m.–5 p.m., Tuesday–Sunday (daily in summer months). Besides seeing exhibits of historic presses, visitors can purchase handmade books, broadsides, posters, cards, and journals (113 Lincoln Ave., Santa Fe; 505-476-5200).

Power & Light Press sells witty greeting cards, posters, and tote bags online and at its Silver City location, as well as at Spur Line Supply Co., in Albuquerque; Ampersand, Dandelion Guild, Hyperclash, and Meow Wolf, in Santa Fe; Black Diamond Curio, in Taos; and Paper Source stores in 30 states (601 N. Bullard St., Silver City; 207-772-6584).

The Southwest Print Fiesta, organized by Power & Light Press and the Mimbres Region Art Council, takes over downtown Silver City October 11–13, with shows, demonstrations, and hands-on opportunities for all ages.

Village Press Print Studio is open Monday–Friday; hours vary. Enjoy a freshly made espresso and peruse letterpress pieces and artwork. Classes are offered occasionally; experienced printers can rent time on the presses (601 1st St., Magdalena; 575-418-6431).

Blossom Merz at Wildland Press will help you design a custom business card, stationery, birth or wedding announcement, or just about anything else you dream up (2843 NM 14, Madrid; 505-629-0763).

Through workshops and demonstrations, the Santa Fe Book Arts Group shares techniques and tips on creating books by hand—often turning them into sculptures. Enjoy their 2019 exhibit in the Roundhouse rotunda, September 6 through December 13.