Illustration by Jameson Simpson.

AS YOU DRIVE INTO White Sands National Park on Dunes Drive, the one road into the park, the Chihuahuan Desert gives way to ever taller white sand dunes. The sands may look dry, but there is actually more water here, not less. That water makes the difference between gypsum blowing away, like it does everywhere else in the world, and doing what it does only in this unmatched place: forming dunes.

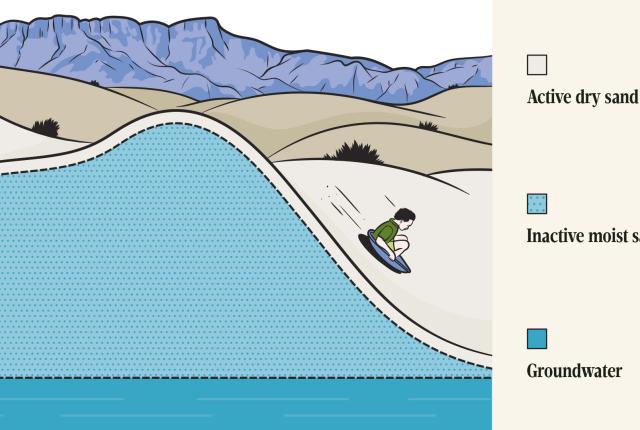

In the Tularosa Basin, the water table sits roughly one to three feet below the surface. The water leaches into the sand and acts like glue that holds it together. “The role of the water is to stabilize the body of sand,” says Ryan Ewing, an associate professor of geology at Texas A&M University who studies White Sands. “You get cohesion of the particles because of a little, thin meniscus of water that’s trapped between them.”

Read More: How the Dunes at White Sands Shift Over Time

Water also transports gypsum from the San Andres Mountains, to the west of the basin, and the Franklin and Organ mountains, in the south, to Lake Lucero and Alkali Flat, at the park. When the brine water in Lake Lucero evaporates, it leaves behind big gypsum crystals, which wind and water then break up and transport into the dune fields. “If you don’t have a big playa to form the sand, and the soil moisture and the high water table to hold that sand once you form it, then it just blows away,” says David Bustos, resource program manager with the Park Service.

For most of the year, the pore space of the dunes (the space between the grains) holds the maximum amount of water possible against the pull of gravity. Precipitation—or its lack—dramatically affects it. In the driest months, March through June, groundwater is pulled up from the shallow water table and evaporates, even as the sands hold on to their moisture. During summer monsoons, the extra water easily replenishes the water table, and sometimes even overflows, creating deep pools between the dunes and flooding the picnic area.

Read More: Prehistoric Footprints at White Sands Tell Rich Stories

The best way to perceive the water at White Sands is one that takes patience. Bustos recommends sitting in an interdunal area beginning a few minutes before sunset. As the sun sets, the temperature drops and the breezes pick up. You should notice a hint of dampness in the air—this represents the soil moisture rising as the sun goes down.

Streams flow into the Tularosa Basin from the San Andres Peaks but then disappear among the dunes. Then, on the far eastern edge of the monument, water reappears and flows for a short distance in what is called the Lost River. The water seems to flow in the direction opposite that of the dunes, though it’s unclear exactly why.