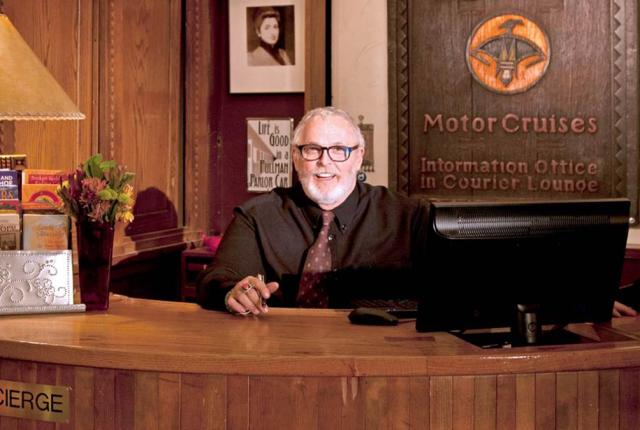

Steve Wimmer gave perfect service as the gregarious, huge-hearted Chef Concierge at La Fonda on the Plaza. Photograph courtesy of La Fonda on the Plaza.

ON OCTOBER 19, 1989, a tall, red-headed, 41-year-old single man from Pylesville, Maryland—a rural town about an hour northeast of Baltimore—showed up at La Fonda Hotel in Santa Fe, applying for a part-time job as a relief concierge. His name was Steven Wimmer, and he had a pretty surprising résumé.

He listed as references a weaver he knew in Española, a chiropractor in Ojo Caliente, and one of the top economic writers at the International Monetary Fund in Washington. He was working part-time as an assistant to the director of the Film Festival of Santa Fe—a job he hoped to keep if it found more funding—and as a shop manager for an antiques store on Palace Avenue. Before that, however, he had spent nearly 18 years at American Express overseeing travel services for the World Bank. While based in Washington, he traveled the world for the company, earning enough for a decent if not extravagant semi-retirement at the age of 40. He had a degree from American University, where he studied history and became fluent in French and Russian. He had since learned Portuguese, Italian, and Spanish. And he was studying Japanese.

He seemed a little overqualified for La Fonda’s part-time position, which paid $5 an hour. But he was engaging, smart and funny—and clearly captivated by the Southwestern history and culture that so many came to Santa Fe to explore, taste, and take home. In his free time, he drove all over New Mexico in his turquoise vintage Cadillac, visiting pueblos, historic sites, and eateries. They gave him a try.

Over the next 26 years, Steve Wimmer became a Santa Fe fixture. He held court and gave perfect service as the gregarious, huge-hearted, history-obsessed, whatever-it-takes Chef Concierge at La Fonda. As he got more comfortable in the job, he became more flamboyant in his manner and appearance, with bright bolo ties and oversize glasses, more ambitious with his solutions to the challenges of hotel guests, and more ingenious and extravagant in his efforts to delight them. He could get impossible, last-minute restaurant reservations and tickets—especially during the frenzied weeks of the Santa Fe Opera and Indian Market. During quieter seasons he could be more creative.

One year jewelry designer Dian Malouf called to say she and her husband were on their way from Dallas for a last-minute visit just before Christmas. Awaiting them in their room was not only cold champagne and warm hors d'ouevres but a real Christmas tree that Wimmer had procured and decorated.

Another time, after telling a regular guest about his most prized piece of Native American art—a black Santa Clara pot—he decided to have one made for the guest … in chocolate. He asked renowned chocolatier Haywood Simoneaux of Todos Santos to make a mold of the pot (which he did, gingerly, terrified the pot would break during the process) and presented the chocolate version as a gift. (Because Wimmer had a lot of VIPs to take care of each year, he never let a brainstorm be used only once. The Maloufs were so moved by their tree that he started doing a few each Christmas, keeping track of who got which decorations so they could be rotated. Simoneaux was later asked to make a few more chocolate pots with that mold, and also made chocolate copies of Wimmer’s most over-the-top concho belt, with silver leaf applied.)

When a first-time guest emailed from Amtrak’s Southwest Chief that he would arrive too late from Kansas City to have a shirt laundered for an event that evening, Wimmer had a clothes rack put up in the gentleman’s hotel room, and brought in a dozen of his own shirts—in various sizes; his weight fluctuated—in case one might work.

“As long as it’s legal and not unkind,” he would say, “we can do it.”

As news of his recent passing flitted among staffers, guests, and an army of “FredHeads”—fans of hospitality entrepreneur Fred Harvey and his onetime chain of Harvey Houses, which La Fonda once was—remembrances flowed forth.

“Steve was one of a kind,” recalled Jenny Kimball, La Fonda’s chairman of the board. “We adored him even when he drove us crazy because he had such an amazing mind and talent. Creative beyond belief and always penniless since, no matter what his budget was, he overspent it and then gave and spent all of his own money on our guests and his friends.”

“He was just everything in one man,” Malouf said. “Someone you never forget in your life: interesting, well-travelled, well-spoken, an original.”

Wimmer placed no boundaries between his professional and personal lives. “He networked people all the time,” said his friend and final La Fonda concierge protégé Rebecca Mascolo. “I once mentioned that I hated my husband’s job, and he came in a couple days later and said ‘I got him a new one.’ He could get people to say ‘yes’ to him. They knew he had integrity and taste and a genuine desire to serve. He loved to see how he could sway people toward what they would enjoy.”

“My favorite Steve story,” said his friend and former La Fonda concierge Nancy Helman, “is one Christmas it snowed, like, 38 inches in Santa Fe and we all got stuck at the hotel—Steve, along with some of his favorite guests like the Slaughters and the Jordans. Steve had a full beard then. He took a break and went to the only room left in the hotel, and he never cared about keeping doors closed. So, he’s lying on the bed, it’s nighttime, his door’s open. One of the Jordan kids sees him lying there and then comes running down the hall yelling ‘Mommy, Daddy, Santa Claus does live at La Fonda!’”

Over the next 26 years at La Fonda on the Plaza, Steve Wimmer became a Santa Fe fixture. Photograph courtesy of La Fonda on the Plaza.

Over the next 26 years at La Fonda on the Plaza, Steve Wimmer became a Santa Fe fixture. Photograph courtesy of La Fonda on the Plaza.

While Wimmer was fascinated with all aspects of culture and history of New Mexico—and had always been a fan of the “dolce vita” of international film, literature, music, and cuisine—he learned about something new as concierge of La Fonda: the fascinating history of Fred Harvey, the family business that created the hotel in the 1920s. From the 1870s through the 1940s, Fred Harvey, the hospitality partner of the Santa Fe Railway, was the dominant national chain in the hotel and restaurant business, from Chicago to the Pacific and south to the Gulf of Mexico, and in all the dining cars of the Santa Fe Railway. It was legendary for its diverse cuisine and chefs; its perfect trackside food service (performed by the all-female wait staff, the Harvey Girls); its amazing architecture and aesthetics (by in-house designer guru Mary Colter); its promotion of Native American art and Southwest cultural tourism; and its fabled hotel managers and concierges, especially at the most important of its dozen large resort hotels, El Tovar at the Grand Canyon and La Fonda.

Both the Fred Harvey company and La Fonda had been sold in the 1970s, to companies not very interested in the Americana of the Harvey legacy. But there were still some older employees and former employees trying to hold on to the Harvey traditions. In some of the original Harvey cities, efforts began springing up to save the Harvey-run hotel and restaurant buildings. Over the years, a great many people heard about a revival in interest in Fred Harvey, the Harvey Girls, Mary Colter, and the ATSF from the Renaissance man behind the round concierge desk at La Fonda, with the original sign from the Harvey excursion business—Indian Detours—hanging behind him.

Wimmer was close to the Ballen family, who owned the hotel during much of his tenure, but he was also thrilled when new La Fonda management, under board chairman Jenny Kimball and architect Barbara Felix, re-embraced its Harvey and Colter heritage through renovation. He admired Allan Affeldt and Tina Mion, the couple who, in the 1990s, saved the Harvey hotel in Winslow, Arizona, La Posada, and in 2014, bought and renovated La Fonda’s sister hotel in Las Vegas, New Mexico, the Castañeda. Wimmer was one of the biggest supporters when the New Mexico History Museum, in Santa Fe, opened a permanent Fred Harvey exhibit. And he was a hero and prized table-mate at the annual Fred Harvey History Weekend every fall.

Stephen Page Wimmer was born October 27, 1947, the only child of World War II veteran Clinton Page Wimmer and Helen Frances Moore Wimmer. He was a precocious, imaginative child who was fascinated by Peter Pan and never quite got over his realization, at age five, that the puppets on the local Baltimore TV show he loved were not actually alive.

His mother died in a car crash when he was seven, and his father remarried—to another woman named Helen—only seven months later. From then on Steve was largely raised by his “Nanny,” his grandmother, with his cousin Mary Sudbrink taking on the role of big sister. The family lived in the largely rural town of Jarrettsville, and Steve attended North Harford High School, where he played clarinet in the school band, the dance band, and the All-State Clinic Band. He was also in the National Honor Society and Drama Club (friends might argue he never left the Drama Club).

Steve Wimmer was fascinated with all aspects of culture and history of New Mexico. Photograph courtesy of La Fonda on the Plaza.

Steve Wimmer was fascinated with all aspects of culture and history of New Mexico. Photograph courtesy of La Fonda on the Plaza.

While attending American University in Washington, he lost his father, who died just before Christmas in 1967, when Steve was 20. He went on to graduate from American in 1969 and the next year was hired by American Express to work in its World Bank Unit, which handled the travel needs for the bank’s 6,000-member international travelling staff. For the first nine years he was a travel counselor—which included perks like the chance to fly on the supersonic Concorde during its inaugural year (he and a friend flew to London for New Year’s Eve, finishing off three bottles of champagne during the flight.) He studied Portuguese at the Brazilian-American Cultural Institute and Arabic at the Middle East Institute to broaden the international clientele he could help, and rose in the company, first specializing in negotiating and overseeing air fares. He later ran the department that managed all the flight, hotel, passport and “special services” needs for the World Bank, and oversaw travel for the organization’s annual meeting in DC, attended by 10,000 economic leaders.

In 1988, he left American Express and relocated to Santa Fe. He had fallen for the Southwest first during a 1981 vacation to Arizona—where he stayed at the Biltmore in Phoenix, and visited the Grand Canyon—and later when he attended a friend’s wedding in New Mexico during the Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta.

While Santa Fe and La Fonda became his family—and he did briefly marry a Portuguese female friend—Wimmer did have one actual family member with him in New Mexico for a while. In 1999, his cousin Mary Sudbrink—whom he called “granMary”—moved to New Mexico after retiring from teaching. They were together for seven years, during which they went on adventures in his Cadillac and Mary occasionally pinch-hit for him at the concierge desk. She also became a docent at the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture. She died at 68 in the summer of 2006, of injuries from an auto accident.

In 2015, Wimmer technically retired because of pulmonary problems, at the age of 68. But he remained in town and continued to help research questions about La Fonda and any other subject folks threw at him; for many of his favorite hotel guests, he kept helping them out with their rooms and restaurant recommendations when they were in town. He also stayed in touch with friends all over the world via email or Facebook, each of which he used energetically, politically, hilariously and sometimes incoherently.

He was helped by current and former La Fonda staff members he had trained and inspired, and friends from Santa Fe restaurants and shops— especially after the global pandemic struck. “It’s tragic he was confined to quarters,” recalled his cousin, Don Sudbrink, “but when you talked on the phone with him you would forget. He had this world of talk and thought and ideas that would lull you into someplace else. He was so stimulating and stimulated.”

“Steve could be impossible in a lot of ways,” recalled Rebecca Mascolo. “After a lifetime of compulsive communication, he started pulling back from people. He couldn’t bear to part with us. It was easier to be mad than to say goodbye.”

She was the last to see him. He was having trouble getting out of bed. Rebecca, with Steve’s friends John Valdes and Everet Apodaca, from Santa Fe Antiques, were taking turns waiting on him (as La Fonda restaurant manager Carol Anglin had before the pandemic.) The morning before Steve died, John and Everet brought him groceries. Wimmer called Rebecca at 8:30 that evening and asked her to come over; he wanted a bowl of strawberry Haagen Dazs ice cream, and he couldn’t get it himself. After she served him and was preparing to leave, he said, “I love you, thank you.”

Steve Wimmer died on March 16. He was 73. He was predeceased by his parents, Page and Helen Wimmer, and his cousin, Mary Sudbrink, and is survived by his cousins Ida May Heidecker, Don Sudbrink, Kristy Sudbrink, and Kurt Sudbrink.

Contributions in his memory can be made to the new Steve Wimmer Historical Research Fund at the New Mexico History Museum. Under “donate to” scroll down to “in memory of,” type in “Steve Wimmer,” and follow the prompts.