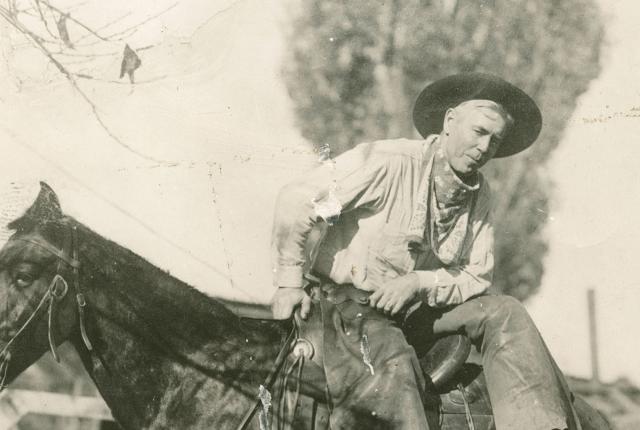

Above: One of the few known portraits of Jack Thorp. Photograph courtesy of the New Mexico History Museum and the Guy Logsdon Collection.

A LONE COWBOY RIDES ACROSS a desert landscape in darkness so profound it shuns shadows. In the distance, a smudge of fire licks defiantly at the gloom. Pieces of a song—None could cut a cow, from corral or herd, as fast as my little horse Joe—reach from the beacon to the rider, a Bar W Ranch hand.

Those words may sound as if they belong in a Western novel or the opening scene of a movie, but they describe something that happened on the New Mexico range in March 1889. On that night, Jack Thorp, a born-to-privilege Easterner who grew into a leather-tough, saddle-wise trail hand, decided to track down the words to songs about cowboy life, a course that proved crucial to the evolution of cowboy culture and the publication of his Songs of the Cowboys, the first collection of its kind.

Printed in Estancia in 1908, the 50-page booklet holds 23 songs. A handful, including the classic “Little Joe, the Wrangler,” were written by Thorp; the rest he collected from cowboys singing in cow camps, at chuck wagons and line camps, in saloons—anywhere Thorp could find them, mostly in New Mexico and Texas.

Read more: Young country traditionalist Will Banister wows ’em from Portales to Piccadilly.

Songs of the Cowboys branded Thorp as a trailblazer and a godfather to all the writers and performers of Western songs who have come since, including members of the International Western Music Association who gather for their annual meeting November 13–17 in Albuquerque.

“Jack Thorp set the standard for the rest of us who write cowboy songs,” says Red Steagall, a popular Western musician and poet who will speak at the conference’s opening-day luncheon. “I have recorded ‘Little Joe, the Wrangler.’ I use it in most all of my performances. It’s one of my all-time favorite songs.”

THORP, BARELY INTO HIS TWENTIES on that March night, had been hunting horses that strayed from the Bar W Ranch, near Carrizozo, when murky evening crowded in on him. “It was pitch dark where I was, Pecos River behind me, Roswell down that-away quite a piece, and somebody’s chuck wagon just ahead, drawn up for the night in the flat sand-dune country rich in grama grass and tabosa,” Thorp recalled in his article “Banjo in the Cow Camps,” posthumously published in the August 1940 issue of The Atlantic Monthly.

Above: The International Western Music Association's 2018 gathering in Albuquerque featured plenty of music—from performers of all ages. Photographs by Sergio Salvador.

Above: The International Western Music Association's 2018 gathering in Albuquerque featured plenty of music—from performers of all ages. Photographs by Sergio Salvador.

He had come upon the night camp of black cowboys from the LFD Ranch, near Roswell. As he rode in, he heard one of them singing “Dodgin’ Joe,” a song about a fast cutting horse. While sharing the LFD hands’ fire, coffee, and chuck, Thorp listened to more songs and asked about “Dodgin’ Joe,” only to learn that his hosts knew only two verses of the ballad.

Thorp was already interested in ballads about horses, cattle, cactus, cowboy work, outlaws, and the land of the West. After his encounter, he decided to devote himself to finding and writing down the missing verses to “Dodgin’ Joe” and every other cowboy song he could snag. The next morning, he sent a note to his Bar W boss telling him where the stray horses were and announcing his leave of absence. Mounted on a horse named Gray Dog and leading a pack horse he called Ample, Thorp set off on a yearlong search for songs.

“He did fieldwork as a cowboy on horseback, riding 1,500 miles across Texas and New Mexico,” says Peter White, a retired UNM professor of American studies and English and co-editor of 1988’s Along the Rio Grande: Cowboy Jack Thorp’s New Mexico. “He was doing something without any real knowledge of what he was doing. That was pioneering work.”

Songs of the Cowboys includes “Windy Bill,” sung to Thorp in the Cornudas Mountains of Otero County; “California Trail,” which he first heard at Horse Head Crossing, on the Pecos River in West Texas; “The Texas Cowboy,” collected at La Luz, near Alamogordo; and “Mustang Gray,” which he picked up in a saloon in La Ascensión, Mexico.

“Maybe cowboy singing was an answer to loneliness,” he wrote in “Banjo in the Cow Camps.” “Maybe it was just another way of expressing good fellowship. Maybe it was several things. Something happened in a day’s work, funny or sad, and somebody with a knack for words made a jingle of it.”

Cowboys added their own verses to songs originated by others, making it tough for ballad wranglers such as Thorp to round them all up. He never did find the missing verses to “Dodgin’ Joe.” “A song-hunter had to pick up his gold in small hunks where he found it,” he wrote.

Above: More from the International Western Music Association's 2018 gathering.

Above: More from the International Western Music Association's 2018 gathering.

Rex Rideout, a Colorado-based music historian and recording artist, credits Thorp with saving songs such as “The Zebra Dun,” which Thorp heard in 1890 at New Mexico’s Carrizozo Flats, and “Windy Bill.”

“These great songs appear in other collections of cowboy songs but were likely found first by Thorp,” says Rideout, who will perform a Jack Thorp showcase at the Albuquerque IWMA gathering. “If he hadn’t heard them in some cow camp, they likely would have been lost.”

HE WAS BORN NATHAN HOWARD THORP on June 10, 1867, in New York City, the son of a prominent lawyer and real estate investor. Thorp learned about horses while playing polo. But he got a taste of cowboy life while visiting an older brother’s ranch in Nebraska and staked his future in the West after his father’s fortune floundered from a real estate deal gone bad.

In New Mexico, Thorp, a big man, six-foot-two, 200 pounds, worked for a mining company in Kingston, rode for the Bar W brand, had a small cattle ranch of his own in the San Andres Mountains of White Sands country, and, in the early 1900s, raised cattle, sheep, and goats on a ranch at Palma, in eastern Torrance County. He served for a few years as a state cattle inspector and, according to his posthumously published book Pardner of the Wind (1945), once got into a gunfight with rustlers.

Read more: From opera to rock, flamenco to folk, here’s your guide to New Mexico music.

The New Yorker turned cowboy was on a cattle drive from Chimney Lake, in Otero County, to Higgins, Texas, in 1898 when he wrote “Little Joe, the Wrangler,” scribbling verses on a paper bag by the light of a campfire. It’s a sad song about a raw Texas kid who gets killed when his horse goes down during a cattle stampede.

Mark L. Gardner, a Colorado-based author and Western musician, says, “All its imagery of the abused young runaway, a lightning storm, cattle stampede, and the final tragic scene of horse and rider mashed to a pulp at the bottom of a draw is as powerful as any Charlie Russell or Frederic Remington masterpiece.”

Thorp first sang it to cowboys with him on that drive and later at Uncle Johnny Root’s store and saloon, in Weed, New Mexico. The song stands as a cowboy anthem, selected number 18 on the Western Writers of America’s top 100 Western songs of all time. It’s been recorded by the likes of Steagall, Don Edwards, Emmylou Harris, Roy Rogers, Marty Robbins, Riders in the Sky, Rex Allen, and many more, including Gardner and Rideout on the CD that accompanied Jack Thorp’s Songs of the Cowboys, a reissue of Thorp’s original collection, edited by and with an introduction by Gardner (Museum of New Mexico Press, 2005).

Thorp himself never made a cent off “Little Joe.” He failed to put his name on any of the songs written by him in the collection, most likely, Gardner says, because he wanted people to accept them as pieces sung by old-time cowboys. It must have later chafed him to know that radio yodelers and silver-screen serenaders were making money off his song while he, the real cowboy who had written it, could not. He knew those other fellows weren’t the real deal because they had, for the most part, beautiful voices. “I never did hear a cowboy with a good voice,” he wrote in “Banjo in the Cow Camps.” “If he had one to start with, he always lost it bawling at cattle, or sleeping out in the open, or telling the judge he didn’t steal that horse.”

Above: More from the International Western Music Association's 2018 gathering.

Above: More from the International Western Music Association's 2018 gathering.

ON JULY 29, 1908, THROP PAID P.A. Specmann, of the Estancia News, $156.50 to produce 2,000 copies of Songs of the Cowboys. Printed on rough stock and bound in red paper, it predated John A. Lomax’s better-known and more widely distributed Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads by two years. Thorp sold copies for 50 cents; today, one in good condition might fetch $1,250.

There is a copy at the Palace Press, a museum dedicated to New Mexico printing at the Palace of the Governors, in Santa Fe. Thomas Leech, the press’s director, is proud to have it, but his most prized possession is the Chandler & Price platen press that printed it. “Popular cowboy culture came out of that book, which came off that press,” Leech says. "Now you can go anywhere in the world and people know about cowboy songs.”

Thorp also contributed to the history of the West in articles about cattle culture, lost mines, outlaws, and colorful characters, many of them written between 1936 and 1939 for the New Mexico Federal Writers Project. J. Frank Dobie, the late Texas folklorist and author, once wrote about the time he visited Thorp and his wife, Annette “Blarney” Thorp, in an adobe house in Alameda, just north of Albuquerque. Dobie planned to stay only an hour or so but lingered through the night listening to Thorp’s yarns.

Thorp was talking to his wife in that house when he died on June 4, 1940, just shy of his 73rd birthday.

“We are still producing Western movies. There are still lots of cowboy singers,” says White. “He was really a person who caught on to something before anyone else did, something that would live 100 years after he died and be an important part of American culture.”

HEAR IT NOW

Western songs take center stage at the International Western Music Association’s annual gathering, November 13–17 at the Hotel Albuquerque. Shop for CDs, attend musical showcases, or find musicians jamming in hotel corridors. For a schedule and ticket prices, click on “event” at westernmusic.org. —OR