Above: Jon Sanchez in his Albuquerque studio. Photographs by Inga Hendrickson.

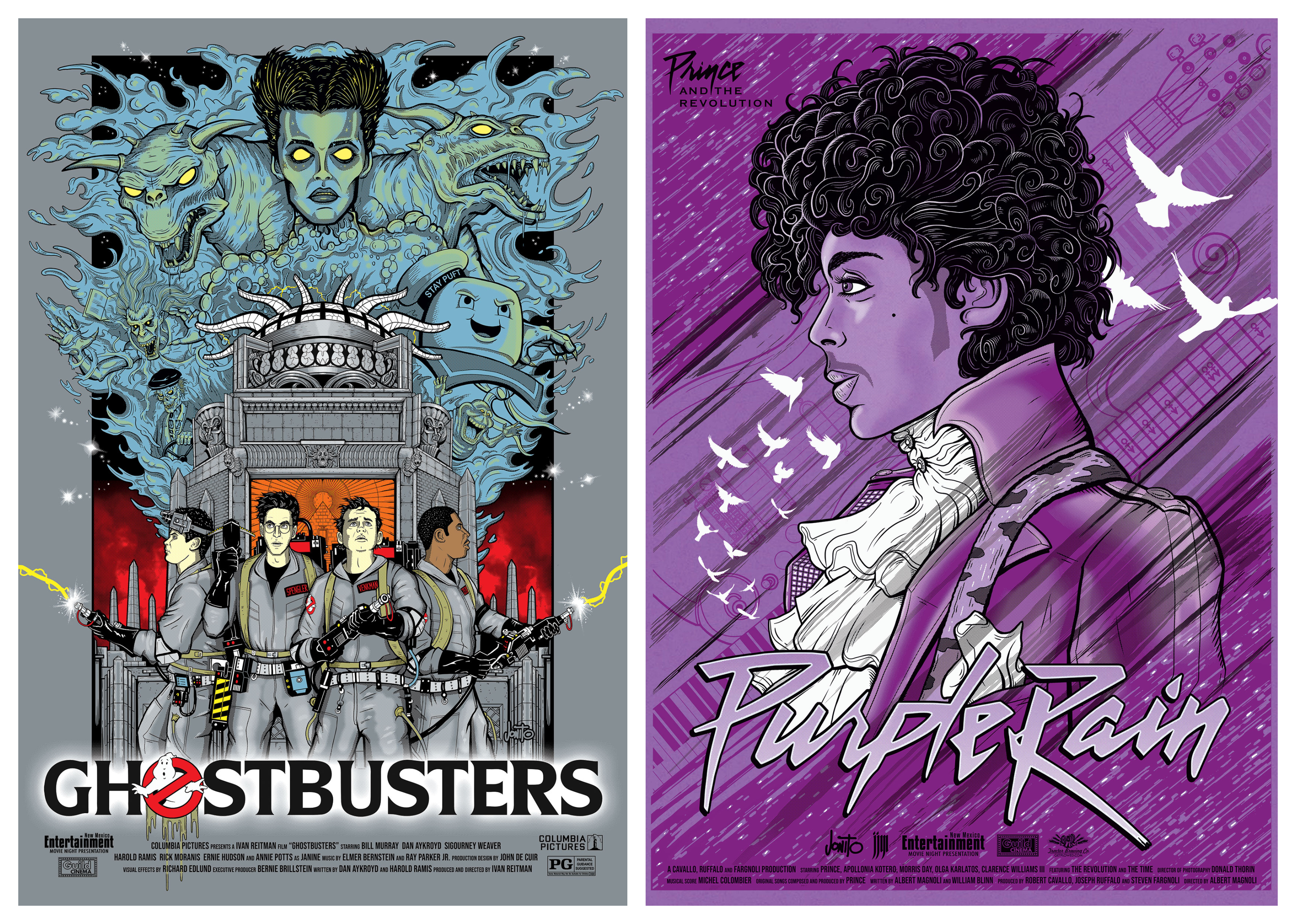

IT’S HOT AND I’VE SPENT MOST of the day at the Hispanic Contemporary Market, on the Santa Fe Plaza, waiting for a cloud to give some reprieve. Jon Sanchez sees me lingering at the entrance to his corner booth on Lincoln Avenue and invites me in. Screen prints fill the space, some framed, others not. I look closely at his movie poster for Purple Rain, remembering the record I used to have and still regret losing in a move. The record cover pictured a purple-clad Prince sitting on his matching purple motorcycle in a haze of darkness and fog with a come-hither look. Sanchez’s poster is more dialed in and focused on the artist himself, no motorcycle, no stoop, no woman peeking out from the doorway.

It’s all Prince—the purple, the eccentricity, the poise.

Designed in 2018 for a special showing of the film at the Guild Cinema, a small and eclectic indie-film haven in Albuquerque, to commemorate Prince’s June 7 birthday, Sanchez’s poster depicts the musician in profile, lace jabot spilling out of his military jacket, and curls rendered like a Greek god’s, all against abstract guitar strings and doves. The purple paper it’s printed on glints with the shimmer of metallic amethyst ink.

There’s another poster for Labyrinth, starring David Bowie, and some more New Mexico–specific designs—skulls, roses, and La Muerte Roja, a screen print of a woman with a calavera face wearing an off-the-shoulder blouse and holding a single rose. A drawn frame mimics wood and arches over her sombrero and long hair, each tendril drawn in detail. It’s a crowd favorite, one that won the First Time Exhibitor Award in 2015.

Over the past decade, Sanchez has honed his chops as an Albuquerque-based printmaker among a community of like-minded artists and friends who share an in-your-face graphic aesthetic—hard lines, bold colors, and a love of pop culture. It’s true camp alchemy and an ideal mash-up for his original art, limited-edition alternative film posters, and band-show posters, all of which he draws, inks, digitally separates, and screen-prints by hand. A regular at local pop-ups, breweries, regional comic conventions, the Albuquerque Museum, the Guild Cinema, and the Hispanic Contemporary Market, Sanchez creates art that by its nature is made in multiples, making it much more attainable than other media.

That means we can all have a piece of Prince.

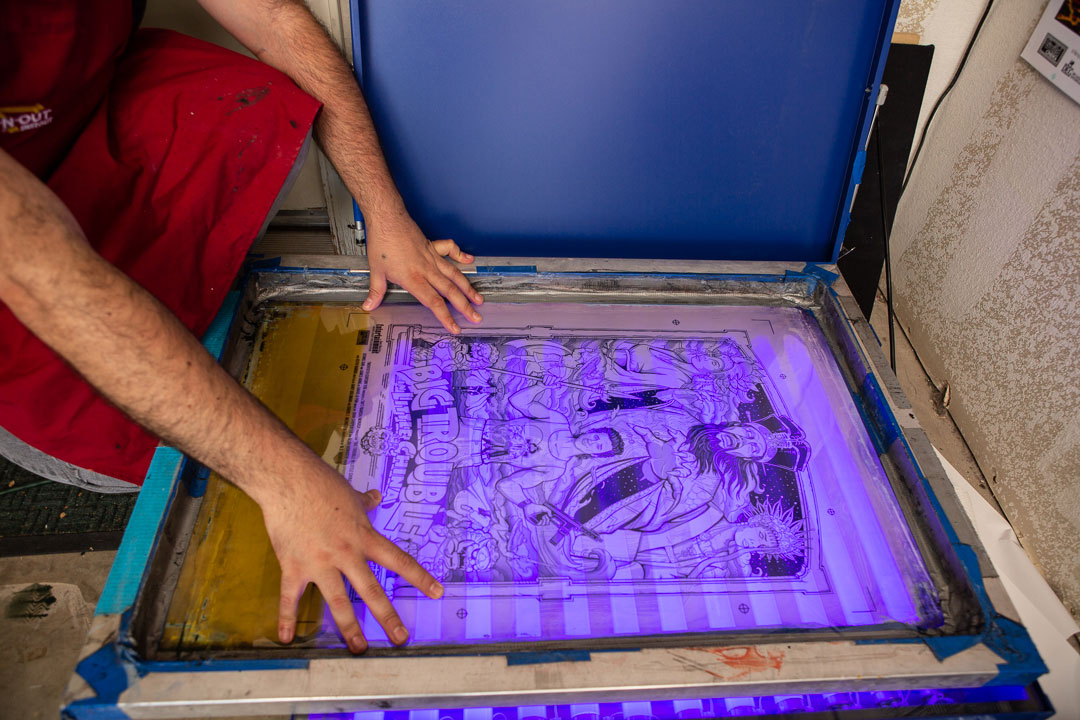

Above: Jon Sanchez setting up a screen for printing.

SANCHEZ'S TINY SIDEKICK, LEIA, IS A congested pug with late-spring allergies. Named for the Star Wars character who leads the Rebel Alliance, the 13-year-old dog sometimes sports a collar with the starbird insignia. She’s even wearing it in the massive 48-inch-square portrait that Sanchez painted of her for the South Broadway Cultural Center’s 2016 group exhibition Old Disciples, New Worshipers. The canvas now hangs prominently in the living room of his home on Albuquerque’s West Side, just off I-40 and Coors Boulevard.

The actual pug, the beloved Leia in his painting, waddles over. Mildly curious and very soft, she seems to snore even when not sleeping, making “tiny whale noises,” as Sanchez puts it. Above the couch where she curls up, her visage reigns, a composition multiplied four times over, Andy Warhol style. It’s his campy ode to the canine, and a painting that deviates far from the staidness of the pet-art genre on the whole. In it, her glassy round eyes look out, like a space dog heroically leading the galaxy into the future, framed by a smooshed snout and droopy jowls painted in colors that contrast with the rest of her round pug bod.

In Albuquerque, Sanchez is known in art circles as “Jonito,” a nickname his cousins coined growing up—classic New Mexico Spanglish with an added diminutive. “I was the conse of the family” (conse is short for consentido, or “spoiled”), he says, and Nana Frances’ first grandchild and “casino buddy.” Hence his cousins baptized him Jonito, pronounced with a long o on the first syllable, to tease him. He was the kid who even got his own special cereal.

Back then, Sanchez and his cousins rented horror and sci-fi movies after school at a movie spot across the street from the family business, Sanchez Income Tax and Accounting Service, off Central Avenue. The operation, started by his Grandpa Gilbert in 1963 and still run by members of the Sanchez clan, was a virtual jungle of office supplies. There was enough paper, boxes, and highlighters in the back rooms to win over any eighties kid’s heart. He rendered dinosaurs, superheroes, and Transformers on printer paper taken from the copier room. He drew He-Man comics on long rolls of adding machine paper, which came to life when pulled, like a reel, through the cardboard TVs he also fashioned with a few folds and some scissors. They were his version of motion pictures.

A soft-spoken man who seems always to have a visual pun buried somewhere in an artwork and who still retains that kid wonder, Sanchez signs each of his original silk screens and paintings with the nickname of his childhood. It’s a nod to his family’s playfulness and, of course, his revered grandmother.

Above: Ghostbusters and Purple Rain posters by Jon Sanchez.

Above: Ghostbusters and Purple Rain posters by Jon Sanchez.

IN 2008, SANCHEZ WAS WORKING as a graphic designer at the Albuquerque Journal, where he’d been on staff since 2003. He shared “drawing jams” with his co worker Jeremy Montoya, who would become like a brother, each sketching what they called their “Sharpie murals.” When one drew something, the other added it to it, in an office game of exquisite corpse. There were monsters and sci-fi landscapes, the pair’s first collaborations.

Then Montoya got a call. A local band that was opening for the Indiana-based outfit Murder by Death (named after Robert Moore’s 1976 film of the same name) needed a gig poster and wanted him to design it. He asked Sanchez for his help. “I’d wanted to make a rock poster since college, when one of the art students was making gig posters for bands in El Paso,” Sanchez says, “so we busted out the dusty old box of printmaking equipment,” which he’d kept since his class with Louis Ocepek, a renowned NMSU art professor with a reputation for high standards. Nearly 10 years prior, Sanchez had studied with Ocepek while working on his BFA in graphic design. Montoya designed that first poster, and Sanchez assisted with the screen printing.

“It was a very homegrown operation,” says Sanchez. “We used a little lightbulb that eventually failed, and some of the ink didn’t come through the mesh. Now that I think about it, it’s cool to see where we started. We’re still working in a garage, but we’re just more advanced now. After that, I got the itch.”

The next year, he designed own gig poster for the Tucson-based Americana band Calexico, capturing the desert-noir vibe that still defines the group, with a skull made of thorns and a baby bird peeking out of its eye. “After that, any bands we liked, we reached out to them. More than 50 percent of the time, they said no or never even answered. But we kept the fire alive.”

While the pair collaborated, they also had independent practices. Montoya drafted gig posters for Coheed and Cambria and for Minus the Bear, and Sanchez for bands like Fitz and the Tantrums, Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeroes, and the Dandy Warhols. Sanchez even entered a contest to design a tour poster for Fleetwood Mac. When his design became the official poster for the band’s 2013 tour, he ended up spending his winnings on two tickets to one of their performances.

FOR A LAYPERSON, SCREEN PRINTING MIGHT seem counterintuitive—deconstruct an image to construct it. It’s a laborious process that requires the kind of mind that can think backwards, visualizing the end goal through its constituent elements. “What you see in the print,” Sanchez says, “is the result of many efforts.” A five-color print, for instance, has five layers, each a different color, made with a different screen (a transparency of an image is burned onto the screen with a UV light) that imprints one component of the hand-drawn image onto paper.

Sanchez, now a marketing representative for UNM, blobs the acrylic paint on the press when the screen is in place and pushes it through with a squeegee. The term “registration” refers to getting all those overlapping colors to line up on one single image, a purely analog process that takes an eye for precision.

“I like the magic of the handmade. When you can touch the paper and feel the ink, where it starts and stops. It’s very tangible that way,” he says.

Above: Ghostbusters characters come to life on a digital art pad.

Above: Ghostbusters characters come to life on a digital art pad.

I think about how Andy Warhol was drawn to the medium for the same reasons—for its ability to look mass-produced when it is actually very manual. Ink may not be evenly distributed, registration might be slightly off, and there might even be a drip. You can see it and feel it, the texture of registration, the difference that shows up in each repetition. Produced in a run of 30 or 40, each print can be thought of as an original work of art with many almost-but-not-quite-identical siblings.

Besides the tactile and glittery Purple Rain, Sanchez’s movie poster designs include cult classics Ghostbusters, Big Trouble in Little China, Dawn of the Dead, Galaxy Quest, The Goonies, Heathers, and 2001: A Space Odyssey. The swath reflects the visual culture of an era, when part of the overall creative endeavor of making movies included crafting hand-drawn movie posters that were works of art in and of themselves. Escapist eighties sci-fi and fantasy movies, in particular, generated film posters that often looked as if they might open into bizarre dimensions that felt at once familiar and unfamiliar. Now, as the genre of alternative movie posters revives that practice on a smaller, regional scale, the motivation remains the same: to remind viewers of the elements—the magic—that made those movies and their characters so memorable in the first place.

Read more: Silver City knows how to throw a next-level printing party.

Sanchez’s art brings it all back for me, as one who often feels the pull of nostalgia that comes from recalling icons like David Bowie in Labyrinth, reminding me of my seven-year-old self, even as his line work, symmetry, and color palette infuse the past with newness.

IN THE END, SANCHEZ ALWAYS comes back to the importance of his family and the trifecta of women in his life—his mom, Linda, his sister, Tamara, and Nana Frances. “Anytime I have an event, all my aunties and uncles show up in support, too.” Many of those same relatives also abide by an unspoken agreement to live in close proximity to one another. On the West Side, of course.

Nana Frances, perhaps his biggest art fan, is like a patron saint to him. In 2015, when Sanchez won that first award at the Hispanic Contemporary Market, Nana Frances insisted on making the trip to see her grandson’s booth, even though health issues required her to carry a nebulizer. That didn’t keep her from elbowing other potential buyers out of the way from her wheelchair to purchase the original artwork on which the winning poster was based. When she passed away the following year, the artwork came back to Sanchez.

He pauses, emotional at the memory. “I do what I do because of her.”

POSTER BOY

The Guild Cinema, at 3405 Central Ave. in Albuquerque, features limited-run showings of independent and cult classic films. Keep an eye on the website for the Alibi Midnight Movie series, New Mexico Entertainment Magazine Movie Night presentations, and Bubonicon-sponsored nights, where Jon Sanchez and Jeremy Montoya often sell and give away original commissioned alternative movie posters.

Sanchez participates in each July’s Hispanic Contemporary Market, in Santa Fe.