NEED TO KNOW: NOVEMBER 18, 2012–FEBRUARY 9, 2014. Tall Tales of the Wild West: The Stories of Karl May. An exhibition of first-edition and foreign-language versions of books, film ephemera, and more. Tues.–Sun. 8 a.m.–5 p.m. $9. New Mexico History Museum. (505) 476-5200; nmhistorymuseum.org

Elements of an atypical exhibition are scattered about Tomas Jaehn’s office in the Fray Angélico Chávez Library of the Palace of the Governors: books, posters, and action figures, all sourced from eBay, private collections, even a flea market. The librarian archivist is in the process of putting the final touches on Tall Tales of the Wild West: The Stories of Karl May, for Santa Fe’s New Mexico History Museum. It could be argued that what will really be on display is either utter baloney, or a holy grail of boyhood lore: German author May’s take on the Southwest.

Karl May (pronounced my), who died100 years ago, delivered “authentic” American Wild West adventure fiction to his German countrymen. Of course, you can’t have Wild West adventure fiction without two iconic archetypes: frontiersmen and Indians. In that genre, May, born in 1842, is the most famous and successful Western writer you’ve likely never heard of. His books have been translated into40 languages, and his multimillions of sales eclipse those of Louis L’Amour and Zane Grey taken together.

I first learned about May back in the early 1980s, when I was a teenage exchange student in Germany. My host family enthusiastically ferried me to the Karl May Festival in Bad Segeberg, an annual event celebrating May’s characters, which to this day draws upward of 300,000 people per year. I found myself seated in an amphitheater built into an exhausted gypsum quarry in the 1930s, by the Third Reich Labor Service. Onstage a performance played out, with Broadway-level production values, featuring hundreds of Native American characters singing and dancing their way through an elaborate plot. I was impressed—these lucky German festivalgoers were watching hundreds of Native visitors who had crossed the Atlantic to sing, dance, drum, and put on an entire multi-act play . . . and all in fluent German! At least, that’s what I thought.

In fact, it was a European cast, covered in body paint and wearing flowing, raven wigs. I’m sure my host family explained

the situation in German; I didn’t understand everything they said, but nodded and went along for the ride. In a way, I was lucky. The most authentic way to engage with Karl May is to fall headlong for his illusions, at least for a time.

Born into a family of poor weavers in the Kingdom of Saxony, Karl Friedrich May was a petty thief and embellisher from childhood on, getting caught, inevitably, for progressively illegal acts of cuckoldry and the pinching of furs and watches. May studied to be a teacher, but had his permit revoked permanently for his misdeeds. Becoming a writer reformed him; it gave him new, less explicitly felonious opportunities to be a scoundrel.

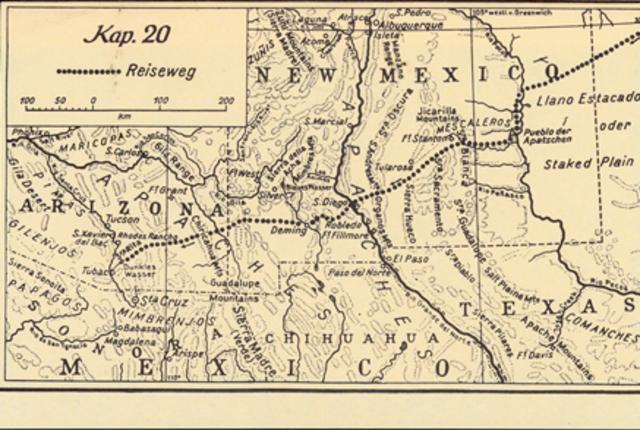

May’s characters, Apache Winnetou and his German friend and blood brother, Old Shatterhand, are friends who play out an eternal adventure tale in Southwest states, though they call New Mexico’s Llano Estacado home. May himself claimed to be a habitué of these stomping grounds, encouraged people to think of Shatterhand as his alter ego, and wore a bear-tooth necklace, fringed leather clothing, and other frontiersy accoutrements. As Rivka Galchen observed puckishly in “Wild West Germany,” a piece in the April 9, 2012, issue of the New Yorker, “Flaubert may have said, ‘Madame Bovary, c’est moi,’ but he never went so far as to wear a housedress.”

May represented himself as someone who understood 1,200 indigenous American dialects. In fact, during his sole trip to the U.S., he ventured no farther west than Buffalo, New York. He was an appropriator of the highest order, taking many liberties with his portrayal of indigenous Americans. Assessing that nomad-averse Germans wouldn’t find the roving Apaches simpatico, he portrayed the tribe as being cave-dwellers. He infused different tribes with the values Germans held dear, and cast non-German American whites as villains.

According to exhibit curator Jaehn, May consulted a vast research library consisting of stories by James Fenimore Cooper and illustrations by Swiss painter Karl Bodmer, which indicates that when May included inaccuracies, he did so consciously. “He had the research notes and the biographies. He didn’t get it out of thin air,” Jaehn says.

As Jaehn wrote in “Karl May and His Wild West,” an article in the Fall 2012 issue of El Palacio, New Mexico’s magazine of state museums and monuments: “His message of German nationalism and Protestant Christian values, and his emphasis on chivalry, manliness, and adventure still appeal to the German audience.” While May was at it, he also culturally colonized the U.S.: the heroes in his books toss back German beer, sing German songs, and read German newspapers.

Is it any wonder that the German audience loved it? So popular is May in Germany to this day, Jaehn says, that his Villa Shatterhand, in Radebeul, is like a German Graceland. There is a well-visited Karl May museum, and online you can even find Karl May fanfiction (additional stories written by fans as homages, a practice popular among Harry Potter devotees). Today, many German fans of Karl May aren’t satisfied by being familiar with his body of work; they further signal their devotion by noting and documenting his flubs and misinformation. Galchen writes in her New Yorker article, “Part of being a Karl May fan, it seems, is correcting Karl May.”

There’s no denying that May was a goofball, a fabulist, a culturally insensitive lout. Regardless, his legacy endures, and is too significant to be thrown out with the liar-liar-pants-on-firewater. What the exhibition intends to capture is a record of influence that spawned an industry of translated editions, action figures, illustrations, movies, and film scores.

Sascha Schneider, an art-nouveau artist, received his big break by illustrating several of May’s book covers in the 19-aughts. Schneider rendered Old Shatterhand and Winnetou as Greek god–like, gratuitously bare-buttocked figures. What does that style of art have to do with the American Southwest? Nothing, but taking such liberties didn’t stop Schneider from lassoing his muse any more than it had stopped May.

Martin Böttcher, composer for the 1960s Karl May movies, also saw his star rise, as his soundtracks and songs climbed the charts and sold thousands of units. The influence of the movies and soundtracks paved the way for Italy’s Spaghetti westerns and their Ennio Morricone scores. In the last 15 years, May has popped up in Germany in new and unexpected ways. One Böttcher song, “Winnetou-Melodie,” was sampled in the 1998 Superboys rap/techno hit “Ich Wünscht Du Wärst Bei Mir” (I Wish You Were With Me). In 2001, a spoof of Karl May movies, Der Schuh des Manitu (Manitou’s Shoe), raked in lots of euros at German box offices.

May-mania (like May himself) did not leave much of a footprint in the U.S., given its überwhelming Germanic gestalt. Although May’s visits to New Mexico and the Southwest were entirely fictional, his wife, Klara, did come here in the 1930s, twenty-some years after her husband’s death, to visit and collect local artwork and mementos. She sent letters to trading posts in Taos, looking for Native pottery to bring back to Germany.

Following in Klara’s footsteps, thousands of May-influenced Germans visit New Mexico each year, and have a reliably strong presence at Santa Fe’s Indian Market. If Karl May’s illusions and confabulations have birthed an enduring tradition of well-versed German visitors seeking authentic Southwestern experiences, who play a part in sustaining Native American artists, that seems to fall into the category of another of May’s signatures: the happy ending.