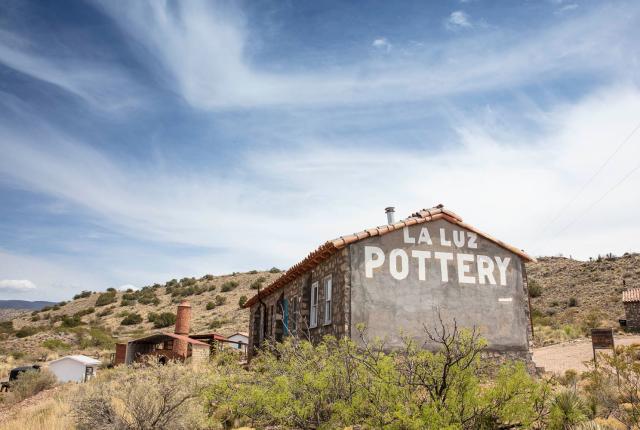

Above: The pottery ruins sit amid scrub-covered hills. Photographs by Jen Judge.

ALL ROWLAND G. HAZARD III WANTED TO DO was dry out, get away from East Coast business pressures, and escape the scorn of his blue-blooded Rhode Island family.

It never occurred to him that he might reinvent himself as the hand-thrown pottery magnate of New Mexico. Take a long drive to California—that was pretty much the best idea he had. He’d already tried therapy with Carl Jung in Europe and hadn’t yet met the group of men who would inspire the creation of Alcoholics Anonymous. That explains why he was on the road, but nothing explains how he got so far off a reasonably reliable east–west route that his car broke down in La Luz, then a town of barely 140 people in the foothills of the Sacramento Mountains, between Cloudcroft and Alamogordo.

He booked a room in La Luz Lodge while waiting for parts, and something about the place infected him. He couldn’t kick it even after a mechanic sent him on his way. The next year, 1929, he went back. With a compulsion that, perhaps, replaced his martini glass, he began buying land. And buildings. And more land. A farm. A ranch. Water rights. Even La Luz Lodge. He mapped out construction plans that required roofing tiles similar to those he’d seen in California Mission–style buildings. He found favorable-clays around La Luz, and he remembered those three Rodriguez brothers back in California. They knew a thing or two about turning pots.

So they struck a deal: He’d bankroll a factory for them in La Jolla, California, and they’d work every summer at the one he was building in La Luz.

What happened after that blends obsession, craftsmanship, fate, mystery, tragedy, and the flat-out weird. Left behind are some hard-to-find pots and the haunting ruins of one man’s beautiful but brief grasp at salvation.

ONE LEGEND HOLDS that the village of La Luz (“the Light”) got its name from the lamps its first residents, in 1866, lit every evening to assure their families in Tularosa, some seven miles away, that they were safe from Apaches, bears, and mountain lions. Other legends credit 18th-century Franciscans. Or a spooky light that bobbed ahead of travelers. Joe Lewandowski explains all this while driving me through the original village, where the rippling curves of terra-cotta tiles grace nearly every roof.

Those competing namesakes are the least of his yarns. A volunteer with the Tularosa Basin Historical Society, Lewandowski details what it took to renovate Alamogordo’s old Plaza Bar for its museum and restore enough of La Luz Pottery’s ruins up in Fresnal Canyon, just beyond the village of La Luz, to make it a tourist attraction. Here’s where it gets weird: A solid-waste consultant, he’s also the guy who dug up the fabled E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial Atari video-game cartridges from the local dump in 2014. That bit of computer-geek folklore fueled the movie Atari: Game Over, but the key point for our purposes is that Lewandowski sold a bunch of the games for $108,000 and donated some of the proceeds to the historical society.

Above: The old laboratory holds artifacts from the pottery-making days.

Above: The old laboratory holds artifacts from the pottery-making days.

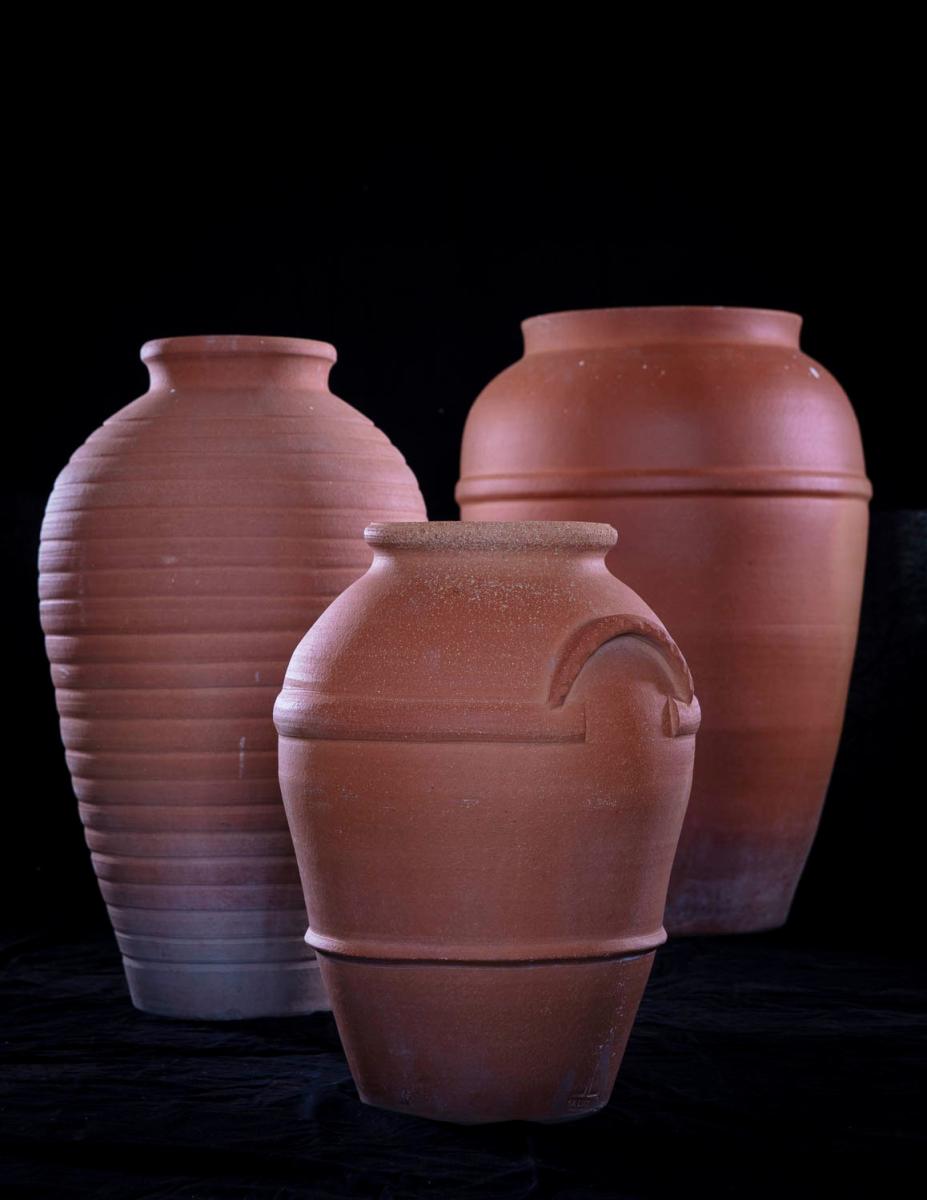

The cash came in handy once the society’s leaders got serious about La Luz. Its former owner gave them its eight structures and 235 acres in 2012, on the condition that they preserve it. Time had not been kind to the compound, most especially the adobe buildings. The property’s most notable feature is a 20-foot-tall clay-tiled chimney that once blew off smoke from the downdraft kiln. In its day, La Luz Pottery churned out anywhere from 80 to nearly 200 varieties of pottery a year—vases, serving dishes, ashtrays, garden pots, birdbaths, lamps, but most especially roof and floor tiles. A June 1931 firing alone produced nearly 16,000 roof tiles and 140 pottery items designed by the Rodriguez brothers. Glazes derived from copper, cobalt, iron, manganese, nickel, chrome, and uranium alchemized into murky purples, deep greens, rich blues, and a muted yellow. Finished pieces were sold in 44 states and seven countries.

In the 1880s, the nation began flipping for American art pottery, with makers like Hull, McCoy, Van Briggle, and Roseville racking up admirers whose successors in recent decades have turned fanatical. Those giants focused largely on dining and decorative pieces with elegant designs and expertly painted glazes. La Luz never matched that production fever. Because its work was hand-thrown, it looks more rough-hewn than those brands. Mainly, though, its major output was those tiles, which won the ardor of architect John Gaw Meem, who helped enshrine Pueblo Revival style as a New Mexico archetype. You can see them at places like the Albuquerque Little Theater and Los Poblanos Historic Inn, in Los Ranchos de Albuquerque. (They used to top St. Joseph’s Mission Church, in Mescalero, but were removed in a recent renovation.) The Tularosa Basin Historical Society Museum has a tile-topped exhibit case filled with decorative pieces. Nearly all of them came from the private collection of Rick Miller, an Alamogordo veterinarian who openly admits to his obsession.

Above: A A A tile-clad chimney stands tall at the Pottery's downdraft kiln.

Above: A A A tile-clad chimney stands tall at the Pottery's downdraft kiln.

“I found my first piece at an antique shop in Artesia,” he says. “Now I’ve got 170 pieces. It’s not easy to find—and it’s getting harder.”

Online auction sites sometimes feature one of the rarities, and buyers shell out serious dough. “The most I’ve spent was $450, but I’ve seen higher,” Miller says. “Even an egg cup now goes for $75, $100. They sold those at the Pottery for a quarter.”

The museum scored a waist-high, unglazed garden pot large enough for a child to play genie in, thanks to a Texas realtor. He called the museum saying he needed to bulldoze a property. If they could move the pot that was on it, they could have it. Lewandowski raced down, strapped it into his pickup, and drove it all the way to Alamogordo, very slowly, one eye on the rearview mirror. “It’s probably worth $20,000,” he says.

Here’s why you hardly ever find La Luz pottery today: Even though Hazard kept the place humming during the Depression, his demons had a flair for finding him. For a while, one of his brothers ran the place, probably when Hazard was back East trying to pull his friend Ebby Thacher out of a major bender and hooking up with the sobriety-seeking Oxford Group. That episode was later chronicled in Alcoholics Anonymous, the “Big Book” that Bill Wilson, Thacher’s onetime drinking buddy, wrote to guide people in despair through 12 lifesaving steps.

Above: Pete Eidenbach takes visitors through he old laboratory, which serves as a mini-museum.

Above: Pete Eidenbach takes visitors through he old laboratory, which serves as a mini-museum.

Hazard himself apparently never found the ultimate cure. Accounts vary, but most say he succumbed to subsequent binges or lost time to an overworked liver. Either way, the halcyon days faded fast. In 1945, Hazard died in Connecticut, just 64 years old. The factory changed hands a few times and pumped out more roofing tiles. In 1955, it fired a final batch. The kiln went cold. But the desire to obtain those pieces of the past continued to smolder.

LEWANDOWSKI STOPS HIS CAR and gets out to unlock the big gate that keeps the factory ruins safe from interlopers. NMSU Alamogordo history professor Pete Eidenbach leads tours twice a month, as weather permits, through the Tularosa Basin Historical Society. Volunteers show up at other times. They’ve stabilized the most endangered buildings and renovated a few others to serve as a visitor center, a mini-museum, and perhaps a one-day artist’s residence. Lewandowski says that’s phase one. Phases two and three include pottery workshops, meditation retreats, and a nature walk.

He leads me through the finished buildings, including the old laboratory (now the mini-museum), where antique bottles with old-timey labels still hold chemicals for glazes that will never gleam. We scrabble around the smokestack, peer into the 12-by-12-foot kiln, and wade through weeds nearly hiding a rusting car. Lewandowski waves his hand at the empty acres on either side of La Luz Creek and describes its former self-contained village—clay mines, houses, gas pumps, a commissary, the blacksmith shop. After it closed, hippies moved in. On one hilltop, they left a rock labyrinth in the shape of a thunderbird. Nearby, their series of upright lumber slabs seem to signify something. Lewandowski calls it “the Stonehenge of La Luz,” but he can’t get it to line up with a celestial event. “Maybe you’ve got to have the right pills or be smoking the right stuff,” he says with a chuckle. Beyond the farthest hill, upscale houses have crept up and down La Luz Canyon. But a peaceful silence has made itself at home amid this ghost of a factory town, where one man hoped to replace his damnable cravings with something more practical.

Above: Classic La Luz Pottery pieces.

Above: Classic La Luz Pottery pieces.

During his tours, Eidenbach says, he tells the story of the factory and its products, but also of Hazard, to whom he can trace a family tie. Each tour takes an hour or two, and visitors get to pop into the lab building, showroom, kiln, and bunkhouse. They take a lot of pictures, he says. Why does that particular pottery fascinate them so? What drives their obsession? Eidenbach isn’t sure.

Some years back, he says, his mother snapped up three pieces of La Luz at a garage sale. He appreciates them, but maybe not as much as other collectors around the world, the ones who lurk on websites and at antique stores, yearning for just one more piece. It’s different for Eidenbach. He has something else to treasure: the 12 steps that helped him crawl out from underneath his own bottle decades ago. For that he credits a touch of fate and his link to a pottery magnate he never met. “I tend to think my ancestor helped save my life 30 years ago.” Speaking only for himself, he says, that may be the finest of all the things Rowland G. Hazard III ever crafted.

LOOK FOR THE LABEL

Genuine pieces of La Luz pottery carry distinctive marks on the bottom. Look for back-to-back capital Ls topped by a flame to resemble a candlestick. The words “La Luz Trademark” and a model number appear along with it, or sometimes in place of it.

FIRED UP

The Tularosa Basin Historical Society organizes tours of La Luz Pottery two Saturdays a month, by donation. Special tours can be arranged. The society’s museum in downtown Alamogordo provides a good background on the pottery, as well as Otero County’s other claims to fame, including nearby White Sands, the railroad, Franciscan missions, the School for the Visually Impaired, and native sons like World War II cartoonist Bill Mauldin. Admission is $3 (1004 N. White Sands Blvd., 575-434-4438, alamogordohistory.com).

Nuckleweed Place is a culinary gem tucked into a trailer in La Luz Canyon. Open for dinner Thursday and Friday and breakfast, lunch, and dinner Saturday and Sunday, its menu features salads, steaks, and over-the-top desserts (526 Laborcita Canyon Road, 575-434-0000, on Facebook).

For more tips on Alamogordo attractions, go to nmmag.us/alamo-fun.