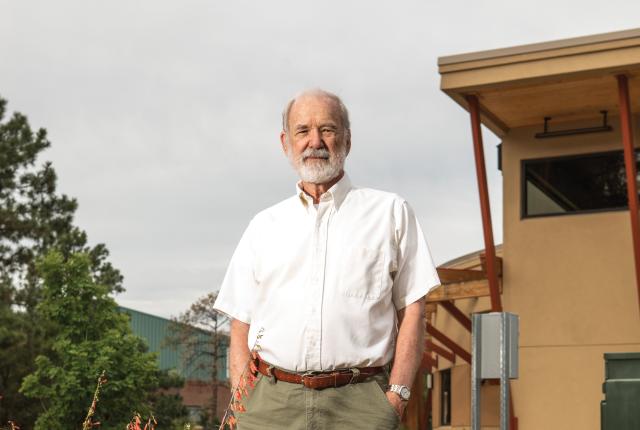

Above: Larry Deaven. Photograph by Minesh Bacrania.

LARRY DEAVEN HELPED FOUND helped found Los Alamos National Laboratory’s portion of the Human Genome Project, work that earned him the lab’s highest distinction, the Los Alamos Medal. Retired since 2015, he has plowed ever deeper into a 45-year passion project: acclimating penstemons, or “beardtongues,” from all over North America to the high desert. At the Los Alamos Nature Center (aka the Pajarito Environmental Education Center, aka “the PEEC”), he commandeers beds where the plants thrive so well that his volunteer badge reads, “Penstemon Whisperer.”

Above: Penstemons.

Above: Penstemons.

I grew up in Pennsylvania, and was doing graduate work at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, in Houston. One night in Houston, I saw a British movie about World War II, and it included aerial photographs of Los Alamos. I saw the mountains and thought, I have to go visit there.

The main reason I wanted to come was that the lab had invented flow cytometers—devices that could measure 100,000 cells in a matter of seconds. They had mathematicians to analyze the data. And they developed one of the first robots to copy the chromosomes. I had opportunities here that I wouldn’t have had if I worked at a university.

I fell in love with the mountains. I used to go backpacking every weekend. I like to go fishing and would hike to high mountain lakes.

I created a backyard rock garden and had a few penstemons. I’d get seeds every year from the North American Rock Garden Society. I had quite a few that grew for a long time. But the Cerro Grande Fire in 2000 wiped it all out.

In 1748, John Mitchell, a British physician, identified the first penstemon, Penstemon laevigatus, in Virginia. They became extremely popular in Britain, because it was a shade of blue they didn’t have.

In some penstemons, the color is inherited, but in some strains the color is continually expressing itself. It’s pink, then purple, or blue. It’s a complex series of genes. If Gregor Mendel had started working with these seeds, we wouldn’t know who he is today. He wouldn’t have been able to codify them.

Penstemons live in a desert or alpine climates where they’re subjected to dramatic changes. If they all germinated at once, they could all be wiped out at once. I think individual seeds have different amounts of germination inhibitor in them—and it’s not species-specific.

The plants begin blooming in late May, early June. But I try to have others that don’t bloom until July. There’s about 2,500 plants here. We have bright reds, many shades of pink, blues, purples, yellow, and a few bicolors. These plants’ colors and intensity of colors aren’t matched anywhere else.

Last year, I got a spontaneous hybrid. I’m calling it PEEC Pink for now, but we’ll probably have a naming contest.

I have penstemons from the Pacific Northwest, Canada, the Southwest, Southern California, Maine, Florida. I’m amazed they grow side by side with plants from the Southwest.

When I was a boy, one of my relatives sent me a package of zinnia seeds. I’ve been hooked on growing flowers and vegetables ever since.

In the dead of winter, I write research papers about the work, and then it’s planting time. When they bloom, I give tours of the garden. All year long, I give talks. The penstemons have become an important part of my life.

People stop me in the grocery store and say, “You’re the guy who raises penstemons.”

I haven’t done my own DNA test. But I think those tests give people a sense of the universality of human beings, and maybe it will help to break down our racial boundaries. Sooner or later we’re going to learn we have more in common than different.

SEE FOR YOURSELF

Besides penstemons, the Los Alamos Nature Center has indoor exhibits and an outdoor fort-building area for kids.