MABEL DODGE LUHAN on D.H. Lawrence: "Of all the places where he lived I know he loved Taos best for did he not tell me so, and write it many times, too, when he was far away? . . . No, there was no one like Lawrence before or since his brief years here: no one like him for making all things new. His genius lay in his capacity for being, a capacity so few people seem to have. To comfort oneself for the absence of him one tries to believe that he was a forerunner, the first sample of a type to come, of those who will defeat industrialism and the mechanization of life, and who will lead humanity out of the impasse where it perishes now.

"[His essay on New Mexico] was one of the really appreciative things that has been written about it. He always felt its magic." —Excerpted from New Mexico Magazine, February, 1936.

THE FIRST TIME I heard of New Mexico, I was living through the depths of a rainy autumn in Cambridge, England. I was a student at the time, renting a small sublet overwhelmed by its owner’s books, with shelves double-deep in books, and towers of books stacked on their sides that quivered when I crossed the floor. One night, ground down by the essay I was supposed to be writing, with the rain sparkling through the stripped branches of a birch tree outside the window, I idly pulled out a small volume. The book happened to be D.H. Lawrence’s Mornings in Mexico, and I happened to open it at the following lines:

THE FIRST TIME I heard of New Mexico, I was living through the depths of a rainy autumn in Cambridge, England. I was a student at the time, renting a small sublet overwhelmed by its owner’s books, with shelves double-deep in books, and towers of books stacked on their sides that quivered when I crossed the floor. One night, ground down by the essay I was supposed to be writing, with the rain sparkling through the stripped branches of a birch tree outside the window, I idly pulled out a small volume. The book happened to be D.H. Lawrence’s Mornings in Mexico, and I happened to open it at the following lines:

“It has snowed, and the nearly full moon blazes wolf-like. . . . risen like a were-wolf over the mountains. So there is a faint hoar shagginess of pine trees, away at the foot of the alfalfa field, and a grey gleam of snow in the night, on the level desert, and a ruddy point of human light, in Ranchos de Taos.

“And beyond, you see them even if you don’t see them, the circling mountains, since there is a moon.

“So, one hurries indoors, and throws more logs on the fire.”

I was spellbound. Life on a ranch in those distant mountains, an English voice recording it so vividly: It was as if the ink were still wet, and I could just about smell the ranch, and feel the cold air wrapped about the mountain, and see that ghostly red light in Ranchos. It hit me suddenly: What was I doing with my life, moldering away in libraries, when I could surely somehow find a way to be there, where this man was? What was I doing with my precious days? It felt as if I had to go to New Mexico.

Some seven years later, I did find a way there, sent by a publisher to write a book about Lawrence in Taos. (The result, Savage Pilgrim, turned out different than planned.) The remarkable thing was not that a young writer was inspired to travel out here by a random paragraph of luminous prose, but that he did find Lawrence’s New Mexico when he came, 70 years after Lawrence had written about it. Essentially, nothing had changed. The heart of Taos, and the land around, the mountains, Pueblo, forest, and lakes—even Lawrence’s little ranch house—were all still just as he had known them. And they still are now, in 2012, nine decades after he was here.

The early cultural pioneers who, in the 1920s, established northern New Mexico as an arts destination, are often lauded for their foresight in lobbying for the building codes that created the unified looks of Santa Fe and Taos. What is less commonly recognized is that they were not only steering this part of the state into a certain kind of future, they were also, even if inadvertently, preserving its past.

As I write this, it’s a blustery fall day in Santa Fe. Golden leaves scurry across the parking lots and hang in clusters on the trees. There is traffic—in fact, cars and trucks are everywhere. The roads are nearly all paved. The city has spread prodigiously in recent decades. Yet wherever I look I see adobe houses, none of them more than two stories high. The sky is still huge. There’ll be wood-smoke in the air soon, as winter rolls closer. A waft of roasting chiles reaches me from a roadside roaster nearby. And the mountains rise in the distance, green, gold, blue, unscarred in any way. This is the same New Mexico Lawrence knew.

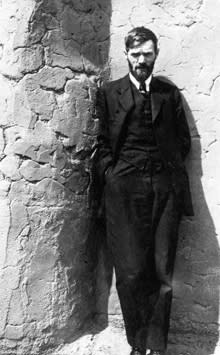

He came here because Mabel Dodge Luhan, the patroness who did so much to put Taos on the map, invited him. In fact, in the letter she sent urging him to come, she included a necklace over which some magic spells had allegedly been uttered, in the hope of not just inviting but compelling him to visit. She wanted him here for two known reasons: He was a writer sympathetic to the new practice of psychoanalysis. His wife, Frieda, was a devotee, as was Luhan herself. She hoped Lawrence would help her grand project of revitalizing and healing what she (and many other “New Thinkers” of the day) regarded as the pathological “dissociation” of modern civilization. We were disconnected from one another, from our labor, from the earth itself. Luhan believed she had found the hope of a cure, in the form not just of analysis, but the indigenous spiritual practices of Taos Pueblo, near which she lived. If her message of renewal appealed to the itinerant, innovative writer, he might become an important broadcaster of it.

At the same time, Luhan had hopes Lawrence would write a great novel—if not the great novel—of America. He had, she thought, done this for England with Sons and Lovers and Women in Love, and, more recently, Australia with Kangaroo. Why not for America, too? And what better place to do it from than Taos, the fount of the new vision for America, of which she was part of the spearhead?

Lawrence, for his part, was in the middle of his “savage pilgrimage”—his worldwide search for what he called an “elemental” civilization, rich in connection to the earth. It’s an odd paradox that the globe-trotting writer should have been desperate to find a deep connectedness to locality, to the earth, given his endless travels. It’s almost as if he might have been searching for his own lost roots in an English mining community. He had grown up with the daily spectacle of his father emerging from “the pit” each afternoon black with coal dust from head to foot, coated in the very innards of the earth where he worked.

Before reaching New Mexico, Lawrence had spent time in Sicily, the Alps, Sri Lanka, and Australia. Generally, he had been favoring high, dry climates. He knew by now that he had tuberculosis, and quite apart from his quest for the right kind of civilization, he was also searching for the right kind of climate, one that might bring about a cure for his lungs. At the time, New Mexico, unlike California and neighboring Arizona, welcomed consumptives, with several sanatoria and famously good air (which it still has).

In the end, although Lawrence declared that “New Mexico was the greatest experience from the outside world” that he had ever had; although he wrote with passionate nostalgia for his ranch above Taos after he had left it; and although that ranch was in fact the only house he would ever own (Luhan gave it to the Lawrences), he nevertheless did not write the great novel of New Mexico, let alone of America, or any novel at all here. Instead he wrote The Plumed Serpent, a novel of Mexico, where he had spent three months on an excursion from Taos. He also wrote a series of wonderful essays about Native American dances, but these are mostly set in Arizona.

What Lawrence did write about New Mexico is primarily a collection of short pieces of prose published in Phoenix, the two volumes of his posthumous works. It is an oddity about Lawrence that somehow the books at which he labored most directly, such as the novels, are arguably not his best. Rather, when he was relaxing, as it were doodling, leaning back against the tree at his ranch where he loved to write, a notebook in his lap, it seemed his vivid genius was in full flood, and he was most able to capture a mood or atmosphere, a character, a relationship. You can see this perhaps most of all in his poems, a large handful of which have made their way into the 20th-century canon, burning with an unparalleled intensity all their own. The other place it happens is in his writing about place. And of this genre, his New Mexico fragments are perhaps the best examples.

In rambling, free-form essays like “New Mexico,” reprinted in this magazine in 1936, Lawrence roams through philosophy, geography, civilization, personal history, and transcendent meditation on humankind’s relationship with the earth. He not only reflects on the place of tribal wisdom in our shallow modern way of life, but ruminates on the beauty of the landscape here with a restless freedom that is exhilarating to follow.

I think New Mexico was the greatest experience from the outside world that I have ever had. It certainly changed me forever. . . . the moment I saw the brilliant, proud morning shine high up over the deserts of Santa Fe, something stood still in my soul, and I started to attend. . . . In the magnificent fierce morning of New Mexico one sprang awake, a new part of the soul woke up suddenly and the old world gave way to a new.

There are all kinds of beauty in the world, thank God, though ugliness is homogeneous. . . . But for a greatness of beauty I have never experienced anything like New Mexico. As those mornings when I went with a hoe along the ditch to the canyon, at the ranch, and stood in fierce, proud silence of the Rockies, or their foothills, to look far over the desert to the blue mountains away in Arizona, blue as chalcedony, with the sagebrush desert sweeping gray-blue in between, dotted with tiny cube-crystals of houses: the vast amphitheater of lofty, indomitable desert, sweeping round to the ponderous Sangre de Cristo Mountains on the East, and coming up flush at the pine-dotted foothills of the Rockies! What splendor! Only the tawny eagle could really sail out into the splendor of it all.”

In the ringing final line of this same essay, Lawrence also shows remarkable prescience when he declares, with prophetic certainty: “This is an interregnum,” predicting that modern civilization will have its day, and be replaced by a more earth-centered culture. While this has not happened yet, a lot of people are now hoping it will: that we’ll reduce our spectacular energy consumption and create more local economic systems. Not only that, but from the unusual vantage of New Mexico, there is a plausible argument that, out here, we are still waiting for the “interregnum” even to arrive. We still live in houses made of local earth; we have more and more farmers’ markets selling food that grows locally; the land is spectacularly unspoiled; and far from losing ground, the Native cultures and ways have been growing in prosperity and resilience.

If Lawrence’s New Mexico is still here, what about Lawrence himself?

After tuberculosis took his life in the south of France in 1930, Lawrence’s widow, Frieda, arranged to have his ashes shipped back to Taos. She was building a shrine to him high among the pine trees above the ranch, and she wanted his remains to be its centerpiece. The story goes that Mabel Dodge Luhan had other plans for the ashes, and came up to the ranch to claim them for herself. The two women fought over the urn, and to settle the matter once and for all, Frieda is said to have emptied the container into a barrow of wet cement, ensuring that the remains would indeed wind up in her shrine, in the form of the altar for which the cement was destined.

For decades, this account of Lawrence’s final resting place has been accepted as historical fact. But it’s not the only account. Another oral account that has been passed down from former friends of the Lawrences holds that when his ashes reached Lamy, the rail station just south of Santa Fe, Lawrence’s friend and fellow poet Witter Bynner was charged with collecting them, along with a case of Lawrence’s unpublished papers. He took all the effects back to his home in Santa Fe, where they stayed with him over the weekend before his journey to Taos to deliver them the following Monday.

Over the course of that weekend, sitting alone with his great friend’s papers, he couldn’t resist reading through them. He was dismayed. Here was all the work Lawrence had not published. Yet it was devastatingly clear that its energy and vitality far surpassed his own best work. Then he had an idea.

Friends of Bynner’s report that whenever he was having cocktails at his house, he used to reach for a large bowl on his mantelpiece, which contained some kind of powder. He would take a pinch from it and sprinkle it in his martini before drinking. Speculation is that this bowl may have contained Lawrence’s actual ashes, and that Bynner was hoping to absorb some of his late friend’s brilliance by literally imbibing it. Did he keep the ashes there on his mantelpiece, in plain view of everyone, and meanwhile send up some sweepings from his own fireplace to Frieda in Taos, for use in her shrine?

Whatever the truth, it is Lawrence’s spirit that still resides in New Mexico. As Mabel Dodge Luhan said of him in her introduction, he shared a special capacity with New Mexico itself. Just like the land here, his spirit “awakens [people], stimulates them, makes them more essential; it reveals their buried life, and shows them up; it excites them, making them realize the color, taste, sight or sound of unspoiled natural life.” Which is the very thing that drew Lawrence, and still draws people, to this rare land.