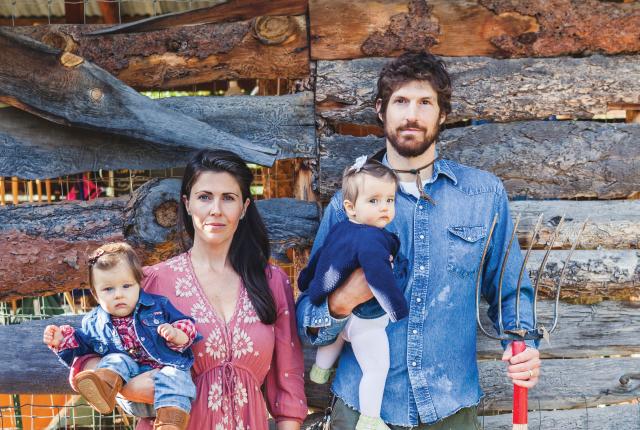

Above: Writer Lander Burr with his wife,Tracy, and children in front of their barn.

MY CORN WAS DYING. Maybe. Actually, I had no idea. Before 2016, I had never grown anything outside of a pot, let alone a plot of blue corn, winter squash, and pinto beans, all irrigated by an acequia. All I knew was that one chilly mid-September dawn, the ends of my corn leaves drooped and their color had turned an ashen yellow.

Looking at the calendar, my stomach dropped. It had now been a month since I had irrigated my plot, and I wasn’t scheduled to receive water for another week. The corn was parched.

I could have uncoiled a hose right then and slaked my babies’ thirst. Except I couldn’t bring myself to do it. I had sown my plot to learn about our local acequia, a centuries-old irrigation ditch. I had already hosed the beds once after the seeds were in the ground, and it felt like cheating. I wasn’t about to do that again.

I texted Dave Kraig, a neighbor who coordinated our section of the ditch, and pleaded for extra water. He replied that the water was flowing to another section, but that he would contact Mario Romero, the man who oversaw that part of the acequia. The next day, I received another text from Kraig.

No word from Mario.

IN THE WINTER OF 2014, my wife, Tracy, and I bought a home in the Pojoaque Valley. Until then we had been living in Santa Fe, but we craved more space and less bustle, a homestead where we could raise our twin girls, so we moved to a plot of land 20 miles north of town. We had met in New Mexico while Tracy was working at an animal sanctuary, and she longed for farm animals to accompany our four yappy little mutts. It never occurred to us that we should have farming experience before purchasing a farmhouse. Tracy had grown up in a West Texas city, while I had been raised preppy in small-town New England. She had learned to mow the lawn; I had grown sprouts in third-grade science class. The rest we figured to pick up on the fly.

We found our dream house and eight acres at the end of a dirt lane that butted up to Pojoaque Pueblo’s bison range. We loved the orchard, the adobe chicken coop, and the field where we envisioned goats romping. We were less sure about the Acequia de las Joyas. We lived at the end of this four-mile ditch, and it cut through our backyard like an odd relic before completing its journey at our driveway. Ancestral Puebloan peoples of the Four Corners region began diverting water for their crops nearly 3,000 years ago. New Mexicans have irrigated from acequias like ours for more than 400 years, diverting water from rivers and springs to grow orchards, pasture grass, gardens, and crops. Acequias have created verdant valleys and riparian habitats in the desert. They have bound communities together as neighbors cleaned ditches and shared water in times of drought. More recently, acequias have persisted in the midst of tumult, even as people have stopped farming, the climate has changed, and urban centers and industry have clamored for more water.

To us, the acequia was just an empty, homely ditch. That is, until it teemed with water. “Baby, come here!” Tracy yelled to me that first time. “The acequia’s flowing!”

We stood there smiling, feeling the humidity rise above the banks, and listening as 45,000 cubic feet of water coursed through the ditch and onto our field. Excitement tingled the nape of my neck, but at the same time, my chest felt heavy. This abundance of water was a blessing, a luxury—and a huge responsibility. I feared squandering it, yet I didn’t know what to do with it.

I spent that first summer trying not to screw up, to make sure the orchard trees stayed alive, our young goats had fresh weeds, and I didn’t flood the house. Once, I forgot to open the irrigation gates and awoke the next morning to water streaming down my driveway and pooling at a neighbor’s front door. I scrambled to avert disaster. By the end of the season, my wife and I often lost the goats in chest-high wild lettuce.

In the spring of 2016, as my second irrigating season loomed, I felt compelled to do more. To be a good steward, I reasoned, I needed to learn something about acequia farming. I needed to grow more than weeds.

AT ONLY 300 YEARS OLD, my acequia is a youngblood. Acequias have spanned five continents over the past 10,000 years, beginning in the Middle East, where the Arabic as-saquiya translates to “the one who gives water.” Acequias traveled with the Moors across North Africa and into Iberia, and conquistadors later brought their knowledge to the Americas. In 1598, when Don Juan de Oñate founded the first Spanish colony in present-day New Mexico, one of his first decrees was to dig an acequia. A few years later, Oñate relocated the colony to what is now the village of Chamita, 16 miles northwest of my home, and that ditch still flows today.

Unlike most other irrigation ditches, acequias are entirely self-governed. Members come together to clean their ditch, elect officers, and vote on improvement projects. The term acequia refers to not just the irrigation system but also the community that cares for it.

This may sound quaint, but in practice, neighborhood democracy can also be rather dull. Weed mitigation and flume repairs don’t make for scintillating cocktail party chatter. When I attended my acequia’s annual meeting, most of the members, or parciantes, played hooky. Before the meeting could begin, Dave Kraig and the other commissioners had to make a flurry of last-minute calls to wrangle a quorum.

That was where I first met Ed Romero, my acequia’s mayordomo, or ditch boss. He wore a straw cowboy hat, scuffed boots, and a rodeo buckle, and he carried the gravitas of a field general. When someone suggested raising membership fees, Romero said that doing so would be onerous for many parciantes. He gave a little dismissive shake of his head. End of discussion.

As the elected mayordomo, Romero was responsible for running our acequia. He distributed water among the parciantes, organized cleanup crews and restoration projects, and decided whether to shut down the ditch if a storm carried too much silt.

In the spring of 2016, I visited Romero at his home, a one-story adobe at the end of a dirt road across the highway from me. While Romero’s cow and 34-year-old horse grazed in a small fenced lot, we sat at a table on his immaculate lawn, near an almost life-size tin horse sculpture. At 60 years old, Romero still looked solid. He wore the same getup, and I learned he had won his buckle in 1988 as a team roper, when he was the heeler. The land had once belonged to Romero’s grandfather, Teodoro Trujillo, and across the field I could see the beige roof of the original farmhouse. Romero remembered when there were no other houses, just alfalfa fields, and the night skies were darker. “You wouldn’t even see a light,” he told me, except from fireflies.

Trujillo made his living as a farmer. He had an apple orchard on one acre, and because he lacked front teeth, he had to squash the fruit against a tree trunk before eating it. Hulking 40-foot semis from Texas used to rumble up the dirt road to buy his produce in bulk.

Romero’s parents lived in Santa Fe, and his mother was county treasurer in the 1960s. Many from that generation left farming to pursue more secure jobs, and later Romero’s peers would do the same. But his parents couldn’t keep him from the farm. “They’d take me over and I’d be crying and they’d have to bring me back. I don’t know why or what—I just enjoyed it here, I guess.”

During those dark nights, Romero went with his grandfather to irrigate the field by lantern light, until Trujillo sprang for a flashlight. The field had a system of lateral ditches, and Romero sometimes catnapped as he waited for the water to reach the next section of field. With his bare feet in the ditch, the water was his alarm clock.

Trujillo served for years as mayordomo, presiding over the acequia’s annual cleaning, the limpia. Parciantes gathered in the ditch with shovels, and often fathers brought their sons when they reached a certain age, marking a rite of passage. Trujillo would pace off, drawing a line in the dirt every six feet or so with a long stick. Each parciante was responsible for cleaning out the weeds and silt in his section, or tarea, making sure to level the ditch bottom. Once Trujillo had inspected each tarea, the party moved on to the next stretch of ditch.

I’ve never been part of a limpia. For several years, Romero has been hiring work crews rather than trying to round up parciantes for cleanings. In Trujillo’s time, there were some 30 parciantes, all with large tracts of farmland. Now there are roughly 100.

As I looked across Romero’s field at the cluster of houses, I wondered how many of the newcomers were like me, people who didn’t know how to level out a ditch, let alone fix a baler. I asked Romero if farming knowledge was disappearing along our acequia. “Oh yeah,” he said. “There’s a lot that’s been lost.”

I inquired what a novice like me could do to help preserve acequia culture. I was thinking of growing a farm plot, but I didn’t tell him this. On some level, I feared he would shoot down the idea. Romero cleared his throat. “It depends on people’s initiative,” he said. “You think it’s important and you’re interested and so you’re willing to take the initiative to move forward.” Until my mayordomo said so, I wasn’t sure I had that initiative. But his words felt like a blessing. Time to get to work.

I DECIDED TO GROW A modest 50-by-50-foot plot of blue corn, beans, and squash. Native Americans have been growing these three, known as the Three Sisters, for thousands of years. They had withstood the test of time, and now I hoped they could withstand my greenhorn farming.

While most local farmers planted in May, I didn’t start on my plot until June. I needed to have my seeds in the ground on June 22, two days after the summer solstice, when I was scheduled to have acequia water. If I waited any longer, my crops would be nipped by frost before they had a chance to mature. Now my whimsy turned to worry.

I had a lot of help from a young man working for me at the time. But feel free to imagine me bathed in golden light, cinematically sweating as I tilled, fertilized, dug furrows, and broadforked beds, all to a John Denver soundtrack. For what it’s worth, I did manage to wrench my shoulder slinging a trailerload of manure.

On the big day, I witnessed a small miracle as water moved where I had intended it to go. A trench carried the flow south through the goats’ field to a corner of my plot. From there, a lateral ditch took the water along the plot’s upper side, and using sandbags, I could dam this ditch to irrigate a couple furrows at a time.

After a few hours, all the beds were soaked and the seeds dibbled. I had only two hours left to irrigate the goat pasture before another neighbor would have rights to the acequia water. It dawned on me then that most of my field would stay dry. For the first time, the water that had seemed so abundant felt scarce.

The plot soon dried out. The beds needed to stay moist for the seeds to sprout, but I was only scheduled to receive water every 16 days. To learn about acequia farming, I reasoned, I should depend on the ditch alone and not resort to my garden hose. If these crops were going to survive, they needed Mother Nature’s help.

It wasn’t forthcoming. Three days after irrigating, a scant shower darkened the beds for just a few hours before the sun sucked them dry once more. The following evening heavy clouds appeared to the south. A band of purple light glowed beneath them, and as I watched, a southwesterly wind picked up, carrying a solitary raindrop to my cheek. I couldn’t turn on the faucet now. This wasn’t just an attempt at farming. It was an exercise in faith. I didn’t wake to rain in the night, and as I walked to the field in the morning, my nose detected no sweet scent of wet earth. I rested a hand atop one of the beds, feeling the fine parched soil already warming in the early sunlight. My stomach fluttered. My faith crumbled. This was no time for hubris. It was time to fetch that hose.

That afternoon, thunder rumbled to the east and dark clouds hid the sun. It began to drizzle, and then rain came in forceful bursts until rivulets streamed off our metal roof. Another shower rolled through that evening, and after putting the goats up, I walked up and down the moist furrows.

Little flecks of green poked through the darkened soil. Some were weeds, but I also saw furled shoots that looked like corn. I knelt down and touched a squash sprout with round symmetrical leaves. It sprang back with vigor. As another mass of clouds hovered above, I vowed to never again resort to using the hose.

FOR THE REST OF JUNE, the rain came every few days. I spent the early mornings plucking the bindweed that I could now distinguish from pinto bean sprouts. One dawn, the clouds turned reddish purple as the sun crested the Sangre de Cristos, and raindrops fell on my shoulders. The air was cool and mild, and I looked up to see the goats grazing the bottom of the field. Two nearby rabbits launched flying kicks at each other. I felt like part of the landscape.

Normally July kicked off the monsoon season, when regular thunderstorms rolled through in the afternoons and evenings. This year, no rain came. The sun was constant, bullying me during the day and leaving me cowed at night. My hands and lips chapped. The county banned fireworks.

The Three Sisters persevered until the acequia flowed again, but once more I stiffed the goats’ pasture. As I walked through the field, parched grass crackled underfoot. The idea struck me that I could take my neighbor’s water for an hour or two without her noticing. I thus contemplated a timeless tradition. Or perhaps a timeless treason. Throughout the history of acequias, neighbors have robbed one another’s water. Confrontations often turned ugly, especially if the aggrieved party had a shovel. Or a shotgun.

In one sense, my idea was novel, perhaps adding to its stupidity. People at the end of ditches tended to have water stolen from their upstream neighbors, not the other way around. One of those victims was Bob Short, the original owner of my house. An octogenarian from Texas, Short had developed a bad back and a shuffle in his step, but his forearms were still thick and bulging with veins. He grew alfalfa for his cows on the field where my goats roam. He would get three cuttings during the season, and he packed the fodder so tightly into his barn that he needed a chainsaw to get it out.

“I was always chasing the water,” Short told me with a raspy chuckle. When the acequia stopped flowing during his irrigating time, he’d follow the ditch until he found the thief. Once a neighbor chased him off with a shovel. Others played dumb, claiming they had the time or even day of the week mixed up. Short then told me the legend of a woman who irrigated from a neighboring acequia and patrolled her ditch with a shotgun, lantern, and bottle of whiskey.

“Nobody got her water,” Short said.

To my knowledge, my water has never been hijacked, but the tradition continues on our ditch. I joined Dave Kraig sometimes when he went to open our acequia’s headgate. On one trip, he noticed that the ditch was dry along another parciante's property when it should have been flowing.

“There’s nothing,” Kraig said. A retired physicist specializing in radiation hazards, Kraig had never raised his voice during our drives. But now he sounded excited. “Someone’s snagging that water!” Kraig called the parciante and told him, effectively, to go chase the water. My neighbor’s tone was polite, but I sensed an undercurrent of frustration suitable to a harried small-town sheriff. “If you find somebody, please let me know; we’ll take it from there.”

By that evening, the case was solved. The culprit turned out to be another ditch member notorious for stealing. Kraig wrote him a citation. If caught again, the thief would face a fine. I never did take my upstream neighbor’s water. It wasn’t that I feared a patroller with a lantern and a shotgun. I just knew, despite my twitchy thirst, that it wasn’t the neighborly thing to do.

AFTER A FEW IRRIGATING SESSIONS, I realized my plot had problems. The ground was lopsided, so the beds nearest the trench received a torrent of water, while only a weak stream reached the beds farthest away. The gradient was also too steep. The bottom of the plot became submerged before I could soak the top part. I tried putting sandbags halfway down the furrows to act as dams, but then I’d get distracted by a mass of weeds or a gopher hole sucking water. By the time I remembered my barriers, the water was already cascading over the sandbags and carving channels along the bed tops. I’d move the bags a few feet upstream, and the dim process would repeat. With a dozen beds, two aching arms, and one frazzled head, I felt like a single parent of 12, and at least half of my charges were always clamoring for attention. Sometimes I just had to tune them out. I’d grab a handful of purslane from a furrow and munch on the tart weed as I gazed east to the mountains from whence my water came. Once, I looked down to see a gopher’s trembling head poking out above the entrance to a hole, his escape routes flooded. With one finger, I reached down and touched his crown. He trembled and blinked his eyes but remained still. I stroked the soft fur a few more times, unaware that this meek little creature might harbor the plague. This time, at least, Mother Nature showed mercy to the neophyte.

In August, the monsoons finally came. More than once, I woke in the night to thunder clapping and water streaming off the roof. In the mornings, beads of water still clung to the corn leaves, leaving my clothes soaked and heavy after I walked through the furrows.

Above: Burr stands in his blue corn field.

Above: Burr stands in his blue corn field.

The goat field grew lush, and my crops flourished. The corn rose to my waist, then my shoulders, and, by the end of the month, overhead. Little shocks of silky purple hair stuck out from the cobs. The squashes bloomed orange flowers that gave way to plumping fruit, and the runners tangled with mats of pinto bean plants and snared my feet. My project, with the modest aim of feeding family and friends, was coming along.

I charted my farming progress through my weeding. In June, one bed yielded a fistful of bindweed. In July, I came away each morning with a plastic five-gallon bucket filled to the brim. And now I had to get on my hands and knees and use the bucket to bulldoze a path through the jungle of bunchgrass, willow shoots, dandelions, purslane, and bindweed.

ON A PLEASANT MORNING after yet another storm, I got in my car and headed north past Española, toward Taos. Like a pilgrim seeking out the mystic on the mountaintop, I was headed to Dixon to see Stanley Crawford.

In 1988, Crawford published Mayordomo, an account of his experience as ditch boss while garlic farming in Dixon. The book won the Western States Book Award, and I can offer my own acclaim. The writing is caustic and soulful, a cross between Edward Abbey and Wendell Berry. The community Crawford depicted was rough around the edges—workers smoked dope during limpias, parciantes scuffled in the school parking lot after annual meetings, and a commissioner brought a loaded .45 to collect delinquent dues. It all made me yearn for a wilder West.

The book also warned of the threats facing acequias. Chief among Crawford’s fears was the possibility that parciantes would sell their water rights, leaving the farmlands dry and the irrigating communities diminished. As a fan, I was eager to meet Crawford, but I also wanted to know whether he thought acequia culture could endure.

As I turned into El Bosque Garlic Farm that morning, I could hear the Embudo River gurgling. Crawford’s property teemed with all the markings of a working farm—piles of firewood, sheds brimming with farm implements and crates of garlic and shallots, a hoop house, a greenhouse, a duck pen, and a field with rows of lettuce, spinach, arugula, kale, endive, carrots, sweet onions, beets, and radishes.

Crawford and his massive Anatolian shepherd mix greeted me outside his house. While Crawford stood nearly six feet four inches tall, he had a disarming slouch that went along with his shorts, sandals, and partially unbuttoned short-sleeved shirt. His quizzical expression was just as I had seen in his book jacket photo—the corner of his mouth hinted at a smile as he raised one eye and crinkled the other.

Crawford was 78 years old, but he ambled with a teenager’s loose-limbed gait as he led me into a cozy sitting room that he and his wife built. The Anatolian and a mother-son pair of heelers were sacked out on the mud floor. I sat on a couch next to a dormant Heatilator fireplace while Crawford took to a chair turned 90 degrees from me. While I looked at him in profile, a hummingbird flitted in and out of phlox growing just outside the window. Crawford waited for me to speak. So, through a long-winded introduction punctuated by “ums,” I asked how his acequia was faring. The answer, it seemed, was complicated.

In a deep voice reminiscent of Johnny Cash without the Arkansas drawl, Crawford told me his acequia community was vibrant. Properties had changed hands since he wrote Mayordomo, but the newcomers were respecting the tradition. Crawford had stepped down as mayordomo in 1996, but the current officers kept him informed. He’d been told that during recent droughts, the various acequias fed by the Embudo cooperated to distribute the trickle fairly.

On the other hand, climate change threatened to make acequia irrigating unpredictable and untenable. Crawford foresaw a future of erratic water flows— “huge runoffs and then nothing.”

Most acequia water begins as mountain snowpack. Good forest cover is critical for keeping the snow from melting too fast, allowing the water to seep into the ground and feed springs and streams gradually. But severe fires and pests thriving in warmer weather could soon decimate these forests, leaving acequias with summer shortages.

Other reports predict severe storms followed by droughts. A decade ago, a massive tempest silted up a host of ditches, including Crawford’s. The acequias eventually received money from the Federal Emer-gency Management Administration, and a miniature track hoe had to maneuver into Crawford’s ditch to dig it out.

The last “desperately dry” years occurred in 2004 and 2005. “I go down to the river every afternoon and sit in the water. It’s not a swimming river, but it’s a nice cooling-off river. Well, it was so bad those two years—there wasn’t enough water, and what water there was, was stagnant—that I did not go in the river.”

Still, Crawford said he was uncertain how climate change would continue to play out in northern New Mexico, since the Sangre de Cristos and the rest of the Rockies lie at the confluence of four major weather systems. “Things kind of collide here,” he said. “It’s very hard to predict what’s going to happen.”

I sank into the couch, my head hurting. The future of acequias felt precarious, regardless of what anyone did to steward them. Before parting ways, I asked Crawford whether he missed being mayordomo. “Oh, not now,” he said, chuckling. “I enjoyed it in a way I didn’t expect to. Now I think I enjoy not doing it.”

I drove down a single-lane road to the Embudo, hoping to clear my head. I crossed a bridge with warped ties for guardrails, parked, and found a path down to the water. As Crawford had advertised, the narrow river was not deep enough for swimming but fine for sitting. I rested on the bank with my feet in the shallows and noticed a little school of hatchlings hovering above their shadows. As the water washed over my toes and I watched those flickers of life, my headache began to lift. In the midst of so much uncertainty, this water held life. I could not help but find hope in it.

IN THE FIRST HALF OF SEPTEMBER, Romero briefly shut down the ditch in order to remove licorice, an invasive plant, and western water hemlock, a poisonous one. The monsoons had ended, but with all the rain in August, I figured I could coast through the rest of the growing season.

I was inundated with squash. By this point, I had given up on weeding, so I shuffled through the furrows like a bushwhacker, feeling for rinds with my toes. I filled my five-gallon bucket with delicatas and buttercups, heaving the 20-pound loads into a sunny hallway to cure or into the arms of any willing takers. Even my mayordomo took two delicatas home after paying a visit.

But on September 19, my idyll ended and I faced the corn crisis—the drooping, dead-looking leaves. Six days later, I learned from Kraig that the other section coordinator had lost his phone, so he had never received my plea for more water. There had been no word from Mario because Mario had never received the message.

That evening, as I went to put the goats up, I heard an unmistakable gurgling sound. I rushed to the acequia and paused for only a second at the lovely, brimming sight. Run, you fool, run! I bolted back to the house to grab my flannel shirt, and my fingers trembled as I put fresh batteries into my headlamp. I wasn’t scheduled to get water for another three days, but it was flowing now, and I had to hurry to distribute the water to my thirsty field.

The rosy dusk gave way to night as I entered the plot. Almost immediately, a corn leaf skewered my eye. Half-blind and weeping, I thrashed through the furrows, inadvertently slugging cornstalks with sandbags. Each time I landed a haymaker, the dry leaves shook like rattlesnakes as the plant fell to the ground. Tiny bugs swarmed to my headlamp and my one good eye. Bewildered moths bedding down on the surviving stalks gave me wary looks. All the while, the water flowed unabated.

Two hours later, I once more gave up trying to soak the beds farthest from the trench. The thighs of my jeans were wet and sullied. My stomach grumbled from missing dinner. I put on my warm shirt, turned off my headlamp, and looked up. The evening clouds had thinned, and I could see the Big Dipper low on the horizon, Polaris suspended above it.

It was early October, and the first hard frost was due in a week or two, around the time the acequia would shut down for the rest of the year. I needed to gather the beans and the rest of the squash soon, and once the corn had dried on the stalks, I would harvest it, too. The season would be over.

Memories from the acequia flickered before me, vivid little moments juicy with life. I knew I would keep stumbling on, chasing the water and the life it held. Someday, perhaps, I would learn to flow along with it, too.

WATER WORLD

Learning by farming isn’t the only way to explore New Mexico’s unique acequia systems. Here are a few places to see them in action.

El Bosque Garlic Farm

Stanley Crawford’s farm is open on Fridays, 3–6 p.m., May through the first full weekend in November. Crawford welcomes volunteers for the garlic and shallot harvests, generally the first and third weeks of June and first and second weeks of July. (505) 579-4288; stanleycrawford.net

Guests can stay in "The Tower Guesthouse," which Crawford once used as his writing studio, starting at $95 a night. stanleycrawford.net, Airbnb, or VRBO

El Rancho de las Golondrinas

The living history museum belongs to a working acequia and grows a crops using traditional furrow techniques. Open Wednesday to Sunday, 10 a.m.–4 p.m., June 1 through October 2. Free daily tours at 10:30 a.m.; docent tours by appointment. (505) 471-2261; golondrinas.org

Valle de Oro National Wildlife Refuge

On a former dairy farm with a working acequia, the refuge uses ditch water to restore wetlands and riparian habitat. Learn when water will flow by contacting the office or visiting the refuge’s Facebook page. Open year-round during daylight hours. (505) 248-6667; nmmag.us/ValleOro; on Facebook

Albuquerque Museum

The Only in Albuquerque exhibit has an interactive demonstration of how water moves through an acequia. (505) 242-4600; albuquerquemuseum.org