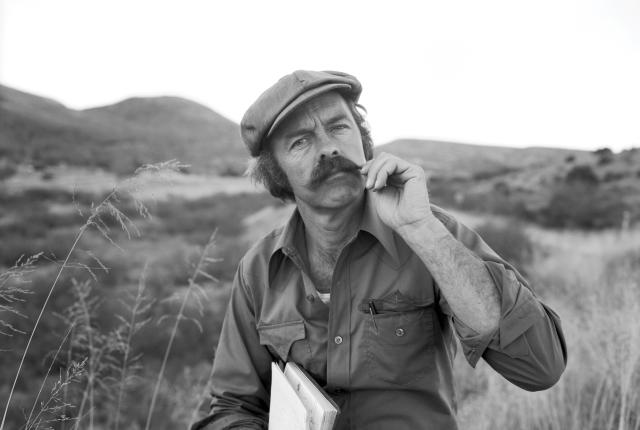

Above: Artist Jerry West in the late 1980s. Photography Meridel Rubenstein/ Museum of New Mexico Press.

“To be born on the prairie means to wander all your life, always being pulled back. It means accident, incident, drama, movement. It always means dreams.”

— Jerry West

THE OLD ADOBE HOMESTEAD is on fire. Jerry West walks down a row of weathered fence posts. Two figures, West’s parents, emerge from their gnarled curves. A barefooted Mildred holds a baby to her breast. Husband Hal is rooted in his cowboy boots. Three sharp strings of barbed wire separate them—and bind them together. Their five children—five ravens—roam nearby.

Dark smoke from the burning homestead spirals into the orange sky. Mildred and Hal appear unfazed. They are pillars of their hard-won patch of prairie earth, both of them unwilling to abandon their stake.

West’s 2003 painting Prairie Pillars with Five Ravens was only a dream. Yet the pressures it expressed were keenly vivid and real. So real that, as with West’s most evocative dreams, the artist merged memory and reverie into a painting.

At 84, West has produced a wide-ranging oeuvre of similarly dramatic dream narratives. Together, they combine his deep-seated reverence for American regionalism with potent recollections of family life on the windswept prairie 18 miles southwest of Santa Fe. West’s paintbrush maps a fantastical world of distant farmsteads with lonely windmills. Rattlesnakes, ravens, lizards, coyotes, and other Southwestern creatures share space with the living and the dead. Storm clouds, fire plumes, or warheads threaten, yet a solid sense of belonging fills the frame. Come what may, the prairie is home.

While the dreams of West the painter inspire his intimate artistic territory, the everyday experiences of West the wanderer cast him as a unique figure in New Mexico’s creative landscape. He stands as an iconic artist and beloved local character, a “Maverick American,” as Southwest art historian and curator MaLin Wilson-Powell calls him in the 2015 retrospective book Jerry West: The Alchemy of Memory (Museum of New Mexico Press). There, cultural critic Rebecca Solnit likens West to a bridge straddling the “old self-reliant prairie world of homesteaders and horse breakers … and the new internationalism of big ideas.”

Nearly a century of history—from the Great Depression to World War II, the new millennium to today—informs West’s canvases, connecting viewers to pivotal points of New Mexico’s social and cultural development. With a flair for magical realism, he propels viewers across time, space, and mind, conjuring and honoring a New Mexico that is long gone but, thanks to West’s brushstrokes, ever present.

“I believe as much in the story as I do in the paint,” he says. “The dreams are in the story.”

ON A SUNDAY MORNING in late summer, West retraces the hopeful and sometimes harrowing path that brought him to his two-story painting studio on the homestead south of Santa Fe where he came of age. Back in the forties, his late artist father, Harold E. “Hal” West, hitched his own dreams to these far-flung flatlands. Today the area remains a nucleus for generations of Wests who, like Jerry, share Hal’s idiosyncratic way of life.

Living in the family’s original adobe is West’s younger brother Archie, who, at 80, West says, is “the family cowboy who still runs cows on the Galisteo.” West’s son, Joe, is down the road, in the place West built for Mildred to spend her final years. Joe, an award-winning country/folk singer-songwriter, is a cult musical hero (see “Joe West’s New Mexico Song-book,” nmmag.us/JoeWestNM). In 2014, the London Telegraph named his Blood Red Velvet one of the year’s best country music albums, praising it as “strange and appealing.” The same can be said of his father’s allegorical dreamscapes.

Guiding a guest across the sweeping narrative of his life in an hours-long conversation, West proves himself a storyteller extraordinaire. “The story of my growing up is a story of family, of the hard years and the magical years, of the love mixed with all the other things that went with it,” he says.

West’s gravelly voice is soft and unhurried. His hands move constantly, gesturing or sketching. His words weave wonder and reverence for the New Mexican way of life, for the land, and for the cultures that collide and coexist here. His laid-back demeanor belies the boldly emotional paintings that fill his studio: A skeletal image of his sickly father looms over his shoulder; a portrait of his mother cradling a rooster commands a wall. Like them, West recounts his story with unflinching honesty.

“In the twenties and thirties,” he says, “no matter who you were or where you came from, it was a really hard time.”

With poor, working-class origins in southern Oklahoma, Hal was no romantic. He was a farmer who, West says, also had talent “as a fine painter of signs.” At the urging of his older sister, Etna, he came to Santa Fe in 1926 to explore its opportunities in art. Etna had arrived a year earlier and made friends with Gustave Baumann, Gerald Cassidy, and other creative movers. Hal easily fell into his sister’s circle but, practical-minded, took a job at a downtown filling station.

“Hal had it in him to be a real thoughtful painter, and Santa Fe opened up a whole world to him,” West says. “But he did everything from a working-class perspective.”

He befriended a co-worker, an Ohio native whose niece taught in a one-room schoolhouse back home. Hal hitchhiked to New York a year later and stopped off to see the friend, who drove him to meet Mildred Olive. He continued to New York and stayed there for a time, but kept looking west—toward Mildred.

West sings an old country standard as his story unwinds. Highways are happy ways when they lead the way to home. Hal picked up Mildred. The two eloped. The highway eventually led back to Santa Fe and a rented home on a tree-lined alameda.

HAL BUMPED THROUGH THE DEPRESSION working as a cowboy on the San Marcos spread south of Santa Fe and at a brief job in Ohio, where Jerry West was born in 1933. Hal got the family back to Santa Fe, where he put in stints at McCrossen’s weaving shop on the Plaza and as a WPA artist crafting prints and paintings for schools throughout the state. “He became known as a cowboy artist, painting from the people’s point of view,” West says.

In 1936, he tried homesteading in La Ciénega and later logged time as a caretaker at Puyé Cliffs, in Santa Clara Pueblo, then as a guard at Santa Fe’s Japanese internment camp and at a German prisoner-of-war camp in Texas. He disclosed little about the nature of those latter jobs, but he saved enough to buy a spread. West was 12 when he and Hal met a man on the Plaza with a 160-acre homestead for sale. “For $500, and $25 a month, he sold it to Hal right there,” West recalls. “Hal finally had his own piece of the prairie.”

West’s memories of visiting the internment camp and his father’s sketches of it inspired his 2009 painting A Westward Glance, a Place Called the “Jap Camp,” a Strange Story. Rows of pitch-roofed barracks fill the frame, beneath a dusty and unusually colorless Santa Fe sky. The scene is viewed from the vantage of Hal’s brother, West’s Uncle Gene, a consummate cowboy who kept watch while riding horseback around the camp’s perimeter. West depicts Gene in a slumped posture, suggesting the overwhelming nature of his task. Hal, however, withheld judgment. “It was a job,” West says.

But a steady job couldn’t dim the economic challenges and worries of wartime. The homestead had no electricity or other luxuries. Only long days of hard work sustained the family. As Hal began struggling with a brain tumor, he worked less, and the pressures intensified. The family’s isolation and economic uncertainty further strained them. Without going into details, West says, “There were dark times, but all families are complicated. Everyone was struggling.”

West struggled, too. He spent nights with Hal to keep him from hurting himself in the throes of severe convulsions. He lost sleep, worried as he was about his father’s survival and confused about how the world would survive the atomic bomb being constructed at nearby Los Alamos.

At school, his talent for drawing and his easy personality fostered camaraderie with teachers and friends. At Santa Fe High School, he launched a lifelong friendship with Jozef Bakos, one of the famed Cinco Pintores, who taught there. “It was almost like he adopted me. I learned painting and plastering from him.”

Bakos likely influenced the awarding of an art scholarship to West, to study at New Mexico Highlands University in Las Vegas with noted painter and printmaker Elmer Schooley—but West turned it down. Instead, in 1952, he and his sister Sarah left Santa Fe to attend Colorado State University. Hal soundly disapproved, and West’s departure caused a rift that took years to repair.

“My dad had a real prejudice about higher education and never pushed it,” he recalls. “But my mother really encouraged me to go to school, and I wanted to go out into the world.”

In Colorado, West excelled at biology and got involved in liberal student politics. In grad school at the University of New Mexico, his adviser egged him on to a doctorate. Again West reversed course. Instead, he began wandering. He married in 1958, put in a stint as an artillery officer at Oklahoma’s Fort Sill, worked at the New Mexico National Guard, and did seasonal work at Gran Quivira with the National Park Service. He taught school at Santa Fe High, first history and later biology, finally realizing, “I wasn’t going to spend the rest of my life dissecting frogs.” By 1964, his destiny suddenly seemed obvious. The path forward was the path back to Hal.

“He and I had been so alienated through the hard times,” West says. “I knew I had to get back into the art mode. I realized it was my calling.”

HIS FATHER HAD LEFT MILDRED by then, entrusting the homestead to her and the children. Hal had survived the tumor, but, somewhere in the midst of the hard times, his prairie spirit died. No longer able to drive or climb scaffolds, he moved to Canyon Road, spending the rest of his life painting and running a small gallery.

West’s reunion with Hal took place there. He visited regularly, built frames for Hal’s paintings, even taught him etching. He also decided to finally study with Schooley at Highlands. After three summers of making A’s, West was invited to enter the graduate program. There, Schooley suddenly downgraded him to a C.

“Elmer was into abstract expressionism as the art god of the times,” he says. “He tried very hard to get me out of being a storyteller.” Dejected, West left the program. Three years later, while West was running the art department at Santa Fe Preparatory School, Schooley persuaded him to return.

More tumult followed. Hal died in the late sixties. West’s marriage, which had produced three children, ended in the early seventies. “It made all the difference in the world that I continued to be a painter,” he says. To support his creativity, he and an artist friend partnered in building custom homes, reserving winters for making art. With a new romance in New York, West spent three of those winters making prints and etchings with international artists at the workshop of African-American artist Robert Blackburn. His artistic course was turning.

“I started doing some really serious dreaming,” he says. He dreamed of his childhood, his family, his New Mexico home. He looked down on the landscape from above, often flying with his brother Archie at his side. He saw his mother with a rooster, saw his sickly father lying beside him in bed. Rattlers writhed beneath his bedcovers, ravens circled the house, and West’s own brain, cinched in barbed wire, hurtled across the New Mexico sky. The dreams laid bare the psychic terrain that held the story of his life.

“I just couldn’t pull myself away from the prairie,” he says. “I had kids, I had land, I had history here. What else was there?”

There was painting. In New York, West began dabbling in dream-inspired imagery. When the romance ended, he returned to Santa Fe, where a Jungian therapist taught him to tap into his tangled subconscious. He confronted hidden childhood fears and anxieties. “Wondering how things had happened was a little mystical,” he says. “I saw the poetry in it.” Meeting photographer Meridel Ruben-stein in the late 1970s, he followed her to Boulder, Colorado. While she taught photography, he translated his dreams to canvas.

At an East Side Santa Fe gallery in 1982, West debuted Prairie Night, an installation of 26 detailed, deeply felt paintings in saturated hues. For theatrical effect, he constructed an environment that immersed viewers in a sleepy blue night sky. The gallery was perfumed with sagebrush and other desert scents. A soundtrack carried the echo of barking dogs, chirping birds, mooing cows, flowing water, Indian chants, children singing, a family laughing. Rabbit tracks traversed the floor, boldly imprinting West’s modern magical realism upon the elite ground of the contemporary art world.

West was 49. He had come to art on his own time and on his own terms, intentionally sidestepping Southwestern art clichés and cliques. Prairie Night was a kind of visual denouement, a creative completion to his life with Hal. It was also the beginning of a new expression and new opportunities in art and life. “It disturbed so many people, but it informed the rest of my painting,” West says. “It made me more determined than ever to do deeply psychological paintings of the West that I know and the people I love. Exploring the human condition, the emotional content of life—that’s where the story is. There is honesty in that.”

Where is the warm summer day when I first saw the green sweet vega, with grama grass waving and water gurgling, with butterflies alighting on clover—and yes, where do we go from here?

So wrote West in Jerry West: The Alchemy of Memory, about his 1981 painting The Prairie World—My Coney Island of the Mind. In the work, a hunter returning with a fresh catch looks down upon his cherished homestead, whose once open rangelands are now ringed by power poles, ramshackle trailers, and mobile homes. West’s 2009 Intricate Shuffle of God’s Living Creatures plays out a similar theme with an in-your-face image of a giant foot that is close to crushing a horned toad, one of many precious prairie creatures that have nearly gone extinct since West’s childhood.

“I’ve seen it my whole life. I’ve seen the development and the drift of this world I am so attached to,” he says. “These paintings are about the psychic pain of seeing it change.”

As the landscape around him has changed, West’s commitment to painting an honest story of his homeland has grown stronger. Through the years, he and his paintbrush have frequently wandered away from his autobiographical prairie pictures to paint other New Mexican people and places. More than two decades working in a studio on the outskirts of Las Vegas, fueled celebratory reflections on small-town life. His reverence for the great Mexican muralists Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros, as well as murals Hal painted in a Plaza grocery, inspired a longtime record of public art. From northern New Mexico senior centers, the New Mexico State Penitentiary, and the Navajo reservation to a mural of Santa Fe’s multicultural history at City Hall, West’s public art projects promote dialogues among the state’s diverse cultures. His home-building projects and friendships with artists and other working-class heroes keep him engaged in communities all across the state.

In 2013, after a yearlong gig at the Roswell Artist in Residence Program (see “Artful Lodgers,” nmmag.us/RAIR), West returned to his prairie studio, where he continues to paint the story of his life—ultimately, he says, the story of all our lives. “My painting is about the interconnectedness of the world,” he says. “We all have dreams and stories to tell.”

With every brushstroke, West honors his parents and the place they staked for him. He still sees them in his dreams. He follows them back to the homestead, where the windmill still turns, and the fire still burns. “Where do we go from here?” he asks. “We don’t go anywhere. We just go right on.”