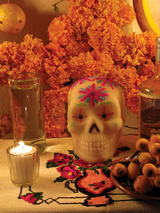

As skeleton-happy New Mexicans know, honoring departed souls is not some eerie voyage into the macabre—in fact, it’s an annual cause for celebration. From the somber to the festive, El Día de los Muertos—the Day of the Dead—is an occasion for descendants to demonstrate their love for the deceased. The event is celebrated in ways large and small around the state, but perhaps nowhere more fervently or on a grander scale than in Mesilla, the mostly Hispanic town that’s part of the Las Cruces metropolitan area.

The festivities take over Mesilla’s historic plaza November 2–4, with dozens of shrines of devotion, dances by an Aztec dance troupe, music, and art exhibits from around the country. “It’s the most traditional and most popular Day of the Dead festival in southern New Mexico,” says Preciliana Sandoval, president of the Calavera Coalition, which sponsors the event to “keep the tradition alive of celebrating our dead.” There are local families, she says, whose members have been erecting shrines to their ancestors annually for over 100 years.

Armando Espinosa Prieto and Craig Johnson, founders of Santa Fe’s Metamorfosis Documentation Project (MDP), a nonprofit that produces documentaries depicting cultural rituals in the Americas, are collaborating with the Calavera Coalition to record the annual events with photographs and film. The community will get DVDs of the documentary to offer for sale, and MDP will include Mesilla’s activities in a feature-length documentary and a large-format art photography book about various Day of the Dead traditions.

Armando Espinosa Prieto and Craig Johnson, founders of Santa Fe’s Metamorfosis Documentation Project (MDP), a nonprofit that produces documentaries depicting cultural rituals in the Americas, are collaborating with the Calavera Coalition to record the annual events with photographs and film. The community will get DVDs of the documentary to offer for sale, and MDP will include Mesilla’s activities in a feature-length documentary and a large-format art photography book about various Day of the Dead traditions.

“Our interest in Mesilla is to have a New Mexican component to this larger documentary,” says Prieto. “It will explore how generations of Hispanic New Mexicans have celebrated Day of the Dead, and investigate how Mexican immigrants celebrate their dead when their graves are still in Mexico.”

The Calavera Coalition anticipates that income generated by the DVD sales will help them restore the graves of 17 children in the San Albino Cemetery. These children, whose grave markers have disappeared, were buried between 1938 and 1940, and are thought to have succumbed to scarlet fever or whooping cough. Community members will be enlisted to help identify the children, and a collaboration involving students from a local school will produce and install grave markers. The goal is to reinforce a sense of historical cultural identity and the meaning behind today’s rituals: to honor the dead.

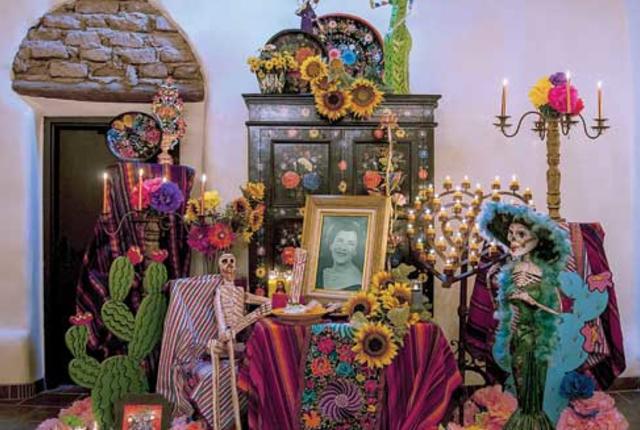

During a recent trip to Mesilla, a number of residents prepared altars for Metamorfosis to photograph. Prieto lit candles for the altar at La Posta de Mesilla, the restaurant “famed for Mexican Food and Steaks Since 1939.” The annual altar was in honor of Katy Griggs Camuñez (1914–1993), a chef and former postmaster. Adorned with a photograph of her as a beautiful young woman, the altar included a large, heart-shaped votive candelabra accompanied by a variety of tapers, flowers, cookies, humorously dressed Day of the Dead figures, and an offering of her favorite meal: enchiladas and black coffee. It all combined to create a joyful atmosphere in which stories were shared and everyone laughed over chilled mugs of Dos Equis.

During a recent trip to Mesilla, a number of residents prepared altars for Metamorfosis to photograph. Prieto lit candles for the altar at La Posta de Mesilla, the restaurant “famed for Mexican Food and Steaks Since 1939.” The annual altar was in honor of Katy Griggs Camuñez (1914–1993), a chef and former postmaster. Adorned with a photograph of her as a beautiful young woman, the altar included a large, heart-shaped votive candelabra accompanied by a variety of tapers, flowers, cookies, humorously dressed Day of the Dead figures, and an offering of her favorite meal: enchiladas and black coffee. It all combined to create a joyful atmosphere in which stories were shared and everyone laughed over chilled mugs of Dos Equis.

“This particular collaboration reflects so well what we strive to achieve,” says Espinosa Prieto. The restoration of Mesilla’s cemetery reminds him of a trip to Michoacán, Mexico, where he met a woman named Guadalupe Dimas. He was telling her about the Day of the Dead project when she interrupted him. “She said, ‘They are not dead until they are forgotten.’”

Miranda Merklein is a Santa Fe–based writer, poet, and teacher.