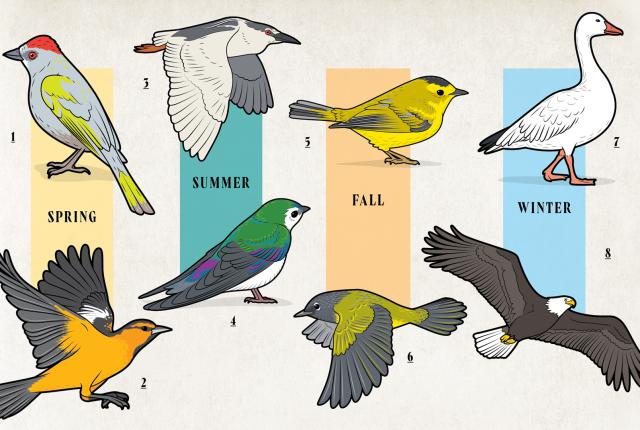

Catch these migratory birds before they leave for the season. Illustration by Chris Philpot.

EACH BIRD SPECIES HAS ADAPTED to different ecological conditions based on the best habitats for feeding, breeding, and raising offspring. When conditions in one place aren’t suitable anymore, it is time to fly the coop to a better spot. “The migrations follow a pretty predictable pattern,” says Chris Rustay, of the Great Backyard Bird Count. “You’ll know the time of year by the birds that show up in your area.”

Spring

The green-tailed towhee (1) can be a bit hard to find. Come April, as the olive-colored bird with a white throat and a rufous-colored cap returns from northwestern Mexico, look for it in the shrubs or sage, digging through leaf litter seeking a tasty bug. During mating season, the males will top a shrub and sing out in a crisp, multi-note trill.

Often, the first bird to show up to a hummingbird feeder in spring, the bright-orange-and-black Bullock’s oriole (2) arrives from western Mexico and eagerly sips on the sugar water between hunts for caterpillars and juicy bugs.

Summer

The black-crowned night heron (3), which can migrate from as near as southern New Mexico or as far as Central America, demands patience. These stunning black-and-gray creatures build their nests along New Mexico’s waterways and wetlands, hiding most of the day before emerging to fish at night. Social with one another, they will even take in and raise chicks that are not their own.

The speedy violet-green swallow (4) migrates from Central America to feed and breed in every corner of New Mexico. Though they’re fairly common in the western U.S., the population declined 28 percent between 1966 and 2015 because of pesticides killing the insects that serve as their main food source.

Fall

In spring, the coppery rufous hummingbird migrates 2,000 miles from Central America, along California’s coast, to British Columbia. On the return south, they follow the Rocky Mountains into New Mexico for a July-through-mid-September stopover.

Warblers also make their way south come September and October. But be sharp: The Wilson’s warbler (5), a bright yellow bird with a black cap, rarely sits still. As one of North America’s smallest warblers, they love trees and woodlands, hunting insects from the ground. The gorgeous gray-and-black MacGillivray’s warbler (6) migrates from Alaska to Costa Rica and back again. As it passes through New Mexico, it can be found hunting insects inside shrubs, willows, and other dense vegetation.

Winter

Winter has arrived in central New Mexico when the massive groups of sandhill cranes and snow geese wing across the blue sky. Snow geese (7) breed in the Arctic, so as that region has warmed, the populations have grown. Cranes and geese are often found together along the Río Grande. Look for them on lakes and in cornfields.

Not long ago, bald eagles (8) were absent in New Mexico. Now, thanks to federal protection, populations have recovered, and the massive bird of prey has reclaimed its traditional territory along our waterways, sitting high in trees or soaring over fields.

Read More: These hot spots offer some of the best birding in the state.