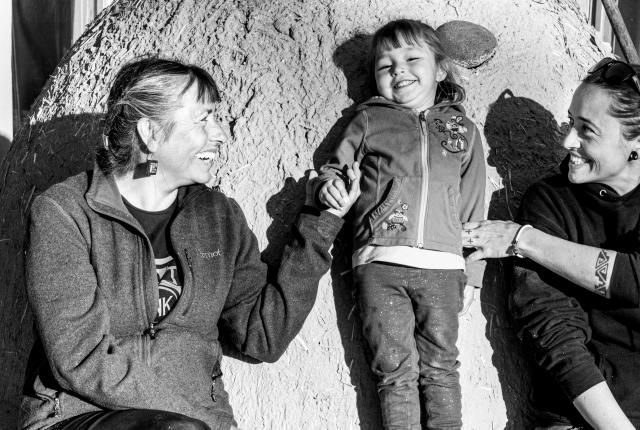

Roxanne Swentzell and her daughter, Rose B. Simpson, sit with Rose's daughter, Cedar. Photograph by Ungelbah Dávila-Shivers.

ON SOME DAYS, WHEN the northern New Mexico weather is nice, I find myself venturing out into the hills, or heading to find some of those rare and sacred spaces where natural water massages the edges of the high desert. I take my three-year-old daughter. As we wander into the hills, she is learning to dodge prickly pears and identify wild edibles. But mostly she looks for pretty rocks, good sticks, and bare earth—eroding hillsides, sandy arroyos, or muddy banks, places where she can draw, dig, push, build. Hands in the earth, she is busied by her natural humanity.

When she plops down on my folded lap, I wrap my arms around her small shoulders and rest my hands on her knees. Thirty-six years of working mud, earth, clay, and metal have rendered scars and wrinkles to my hands. As a child, I studied my own mother’s hands, also prematurely weathered, strong, and capable. As my little hands loved hers, I am now not ashamed of mine.

My daughter and I live across a sandy driveway from the house where I was raised, in the canyon neighborhood of Santa Clara Pueblo. My mother’s is a two-story adobe with a steep, red-tin roof, a home she built for her two babies in the early eighties. The first-floor walls are substantial, adobes laid the thick way and paneled by tall solar windows in rough-sawn frames.

For three decades, the second-floor dormer windows have watched a permaculture food forest evolve—dogs, turkeys, chickens, fish pond, goats, garden beds, and children coexisting on about a quarter-acre of the canyonside. On the hottest days of summer, I sprint in my bare feet across the scorching driveway sand, and once in my mother’s forest, the air is 10 degrees cooler—the most loving of embraces, a body of a home insulated with sustenance.

My mother is Roxanne Swentzell, a farmer, builder, professional sculptor, and cultural preservationist, and my closest ally. Her long career as a well-respected figurative ceramicist is only part of her success, as she is known around the world for the Flowering Tree Permaculture Institute, a nonprofit organization she cocreated in the 1980s to practice and teach sustainable living systems.

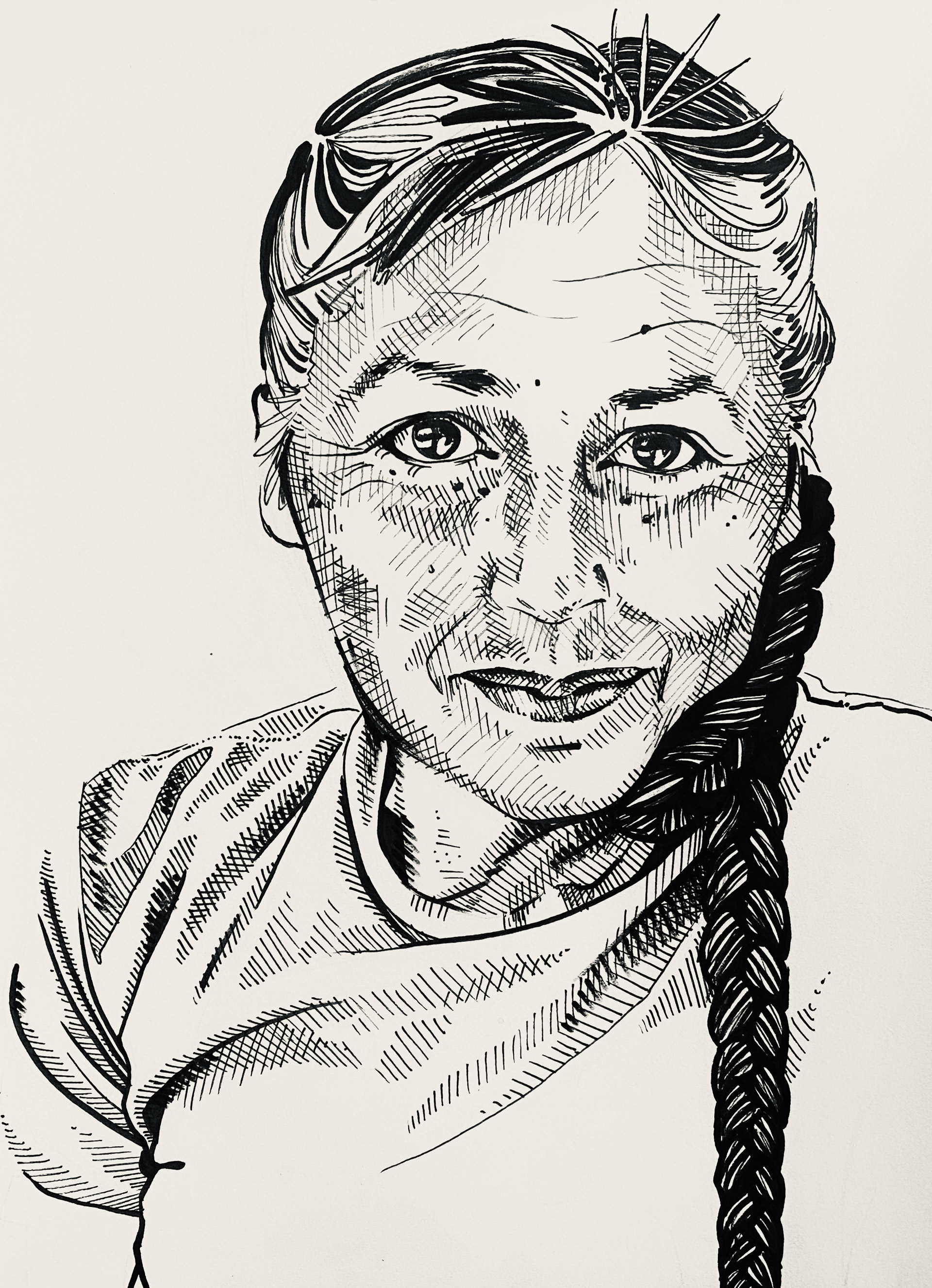

Roxanne Swentzell illustrated by her daughter, Rose B. Simpson.

HER PARENTS WERE BOTH builders. My grandmother Rina Swentzell was an architect with a doctorate in American studies. Grandma Rina worked to demonstrate how architecture reflects cultural belief systems, and how colonization and the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Indian Country construction program negatively affected the lifeways of our Tewa community.

Both of her daughters—my aunt, Athena, and my mother—carried on the family tradition of building with earth and other natural materials, each striking her own balance of innovation and tradition. My mother built our home, farmed the earth to feed her children and community, and made a career of her clay sculpture.

Because of her, I sculpt clay. Because of her, I don’t question whether I am able to build cars. Because of her, I can wield a chain saw and chop an adobe the exact right shape. Because of her, I was raised on our ancestral homelands, participating in our cultural practices. Because of her, I can usually figure out a way to get something done with what I have on hand.

Americans in the 21st century are a culture of teenagers thinking we know best. A close call with a societal crash or pandemic may inspire us to turn to our elders to ask them how they survived without the modern conveniences we have come to take for granted. In our self-righteousness, we may have missed some very important teachings.

As capable as I feel, there are so many times I find myself stuck and have to humble myself and ask Mama which approach she would take or has taken in the past. The more life I live, the more I realize I don’t know.

I call Mama to ask her what she dreamt about last night and to share my dreams. I might ask about the plans for Feast Day cooking or when she might need help to swap tractor implements. I walk my daughter on the river-stone-cobbled path to her house, and she swings the door open to embrace her granddaughter.

There are so many things I know innately about my mother, so it felt almost shameful to ask the following questions. It’s hard to admit that there are things I don’t know about her, to realize that such an untapped and vast knowledge exists within such a familiar and beloved person. We don’t know what we don’t know, and sometimes we struggle to know what to ask.

Roxanne Swentzell (right) teaches her granddaughter Cedar to make pottery with her daughter, Rose B. Simpson. Photograph by Ungelbah Dávila-Shivers.

Roxanne Swentzell (right) teaches her granddaughter Cedar to make pottery with her daughter, Rose B. Simpson. Photograph by Ungelbah Dávila-Shivers.

Please tell me about your first memory of adobe.

I remember the pueblo, walking through the plazas before everything was stuccoed. The houses started to die after they were plastered with cement. But before then, the houses still breathed fresh air and still demanded hands to caress them each year with a new coat of mud. I remember seeing which houses needed some love and which were still fresh from a new coat of mud and straw. I’d stare closely at the texture to see what was captured in the dry dirt, like pieces of sticks, and sometimes I’d even see potsherds added into the mix. It was everything that they scraped up off the plaza floors that went into the mud, recycling the dirt. I remember tasting the mud. Like my mother before me (and probably all pueblo children), I loved to lick the walls. They tasted good, like the smell of rain in the desert.

What is a favorite childhood memory of building with adobe?

We started building our family house when I was about 13. It was a family affair. The bricks were heavy, and we were in charge of hauling them from pallets to the building site. We got strong, strong enough so that we could throw them to each other, saving the walking time. There was a trick to catching them or they would break in our hands, falling to the ground with a thud and the sound of my father scolding us. But when we got into the rhythm of it, like magic, we became a line of bricks floating through the air, weightless. Who knew 20-pound bricks could fly!

I got to build my own cubby room with adobes. I built a curved stairway up to my small loft bed. With adobe I could make any shape, so I sculpted each step to fit the space. The possibilities ignited my imagination. It was sculpture I could live in!

Read more: Acoma Pueblo and Sky City hold to centuries-old traditions. Take a day trip back in time.

I never stopped building with adobe. Having built my own house at the age of 23, I built eight houses and helped on at least six others, but probably the best times I’ve had building was when I, with the help of volunteers, built 18 adobe ovens for the tribe. We gathered—men, women, and children—at the chosen person’s house to build them a working horno out of rock and adobes. Since these were smaller structures than a house, we could finish one in a week. It takes skill to know how to build an igloo out of square adobe bricks, and have it also be beautiful.

I have fond memories of watching kids mix mud and teenagers standing on the keystone adobe to see if we laid it well enough to hold up their weight, and that wonderful feeling of making something out of our own hands that can be used to cook with. It made everyone feel inspired and capable of doing more than they thought.

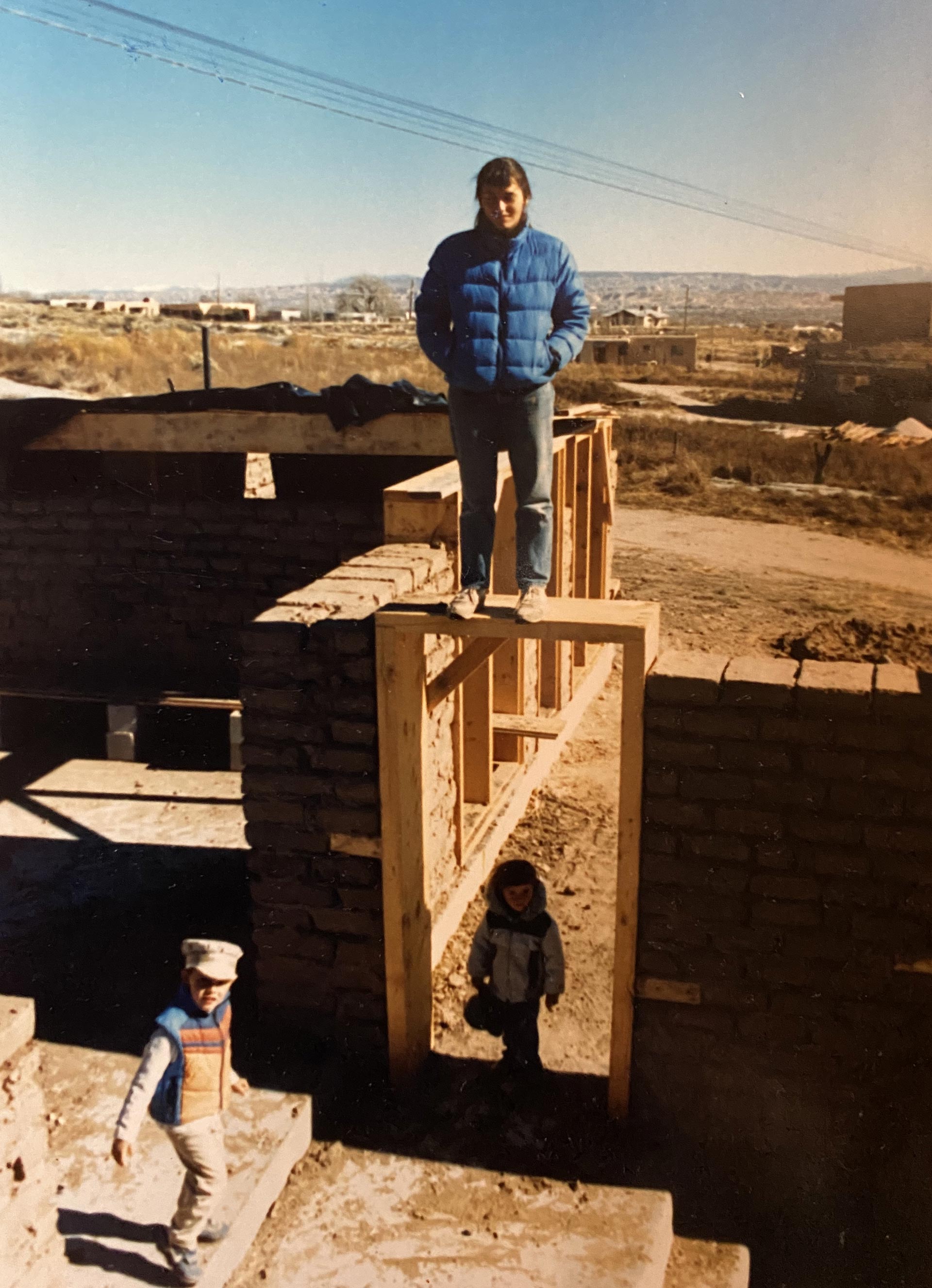

Roxanne Swentzell built her adobe home with the help of her two young children. Photograph courtesy of the family.

Can you tell me what it was like building with me and Porter, as small kids?

When I was building my house at 23, I was a single parent to my two children, who were pretty young but old enough to be put to work at the ripe ages of 3 and 4. I would create a trough shape in the adobe-dirt pile and fill it with water. I told you kids to go play in the mud, which you did happily—what child wouldn’t? In this way you would mix the mud for me to lay the bricks with. All I would have to do is scoop it out as I needed it between your splashing and rolling around like two little pigs in a mud puddle.

By noon I would hose you guys off and we would eat lunch and take our naps. We built our house in this way—no men with construction hats and rules, no heavy equipment, just our days moving mud around, and a need for a home.

The family homestead. Photograph courtesy of the family.

How do you see adobe influencing our future?

I can think of no other building material that can create such an ability for all peoples to work with. Time and time again I have seen that, no matter what age someone is, when they get their hands in some nice mud, they get happy. I built a large straw-and-adobe-plastered sculpture for the Denver Art Museum, in which the public participated in the early stages.

We had to mix mud for coating the straw structure of the sculpture, and everyone was invited to help mix. Hundreds of people helped and walked away dirty but happy. Their handful of mud was added to this permanent art piece, a statement on what is possible with a little mud and straw.

In these times of great changes, we need to look again at our own capabilities. We have strayed too far from Earth and our connection to Her. Building with simple materials like adobe helps us to reconnect. It also lends itself to a creative way of expressing our own uniqueness because of its flexibility. We don’t have to just build boxes; we can live in any shape we can figure out how to sculpt the adobe into! This is a new future, one that could allow our childhood playfulness to come through, and our own imagining of what could be done.

Ceramic pots in the works. Roxanne Swentzell relaxing with her dog. Photographs courtesy of the family.

Ceramic pots in the works. Roxanne Swentzell relaxing with her dog. Photographs courtesy of the family.

I NOW RECALL MOMENTS I might have taken for granted, moments that may someday be important to my daughter. Like how, as a child, I slept curled up against a thick adobe wall, digging my nose into the mud plaster as I met my dreams. Like the time when I was still a small body and could carry only one adobe at a time and I fell, adobe on my chest. I was stuck and called for help. We all had a good laugh.

Maybe my own daughter will also grow to know the consistency of good plaster and mortar mud, how to use a trowel, and which one is the best. I will tell her how I crawled into the adobe ovens because I was the only one who fit through the door, and how proud I was that it was my job to plaster the inside.

She will know the coolness of a summer adobe room, the warmth of a winter fireplace flickering off the earthen walls. She’ll appreciate the silence, the weight, the comforting density, the lack of internet and cellphone reception, as fewer wavelengths bounce around and through our already overactive heads.

I don’t think Mama sat down one day and decided she was going to challenge socially accepted gender roles and lifestyle choices. I believe something deep within her cannot compromise what feels like truth in the human experience, what feels like life, what feels like real living. I don’t think she went looking for it outside herself. I think she figured out how to find it within.