All photographs by Gabriella Marks.

THE CORNER BOOTH that Loren Aragon occupied at the Poeh Cultural Center’s Summer Art Fair at Pojoaque Pueblo was Native American market standard—rectangular tables covered with tablecloths, business cards, and an artist plaque proclaiming his Acoma Pueblo heritage. But the contents were far from expected. Shift dresses in a striking black-and-white geometric print hung next to evening gowns of the richest eggplant-colored silk taffeta.

Fashion design is rare at Native art markets like this one. It’s an unlikely medium among the silverwork, pottery, and weavings that not only are traditional crafts for New Mexico’s Native artists, but also have been sold as collectibles longer. Although Native people have made ceremonial regalia for centuries, those garments aren’t meant to be used for everyday clothing, either for their makers or for buyers.

Still, Native design has influenced mainstream fashion, with designers such as Ralph Lauren and Isabel Marant co-opting “Southwest prints” and “blanket prints” for their labels. In 2016, Urban Outfitters settled a lawsuit with the Navajo Nation after the brand released jewelry, handbags, flasks, and underwear in its “Navajo” line using tribal-inspired textile patterns. That case established the brand’s cultural appropriation as theft. The mainstream fashion houses’ imitations have been far more visible than their authentic counterparts, but that is changing.

New Mexico fashion designers Virgil Ortiz, of Cochiti Pueblo, and Patricia Michaels, of Taos Pueblo, have long carried the mantle for genuine design, though they’ve often done so out of the limelight. That changed with Michaels’ 2012 appearance on the reality TV show Project Runway, and her follow up stint on Project Runway: All Stars in 2014. As the first indigenous designer on the show, she introduced national audiences to fashion with a Native flair. Her success—both on camera and off, including invitations to show at haute couture events in Paris and designing home decor textiles—opened the door for Native artists like Aragon. He and other artists like him have stepped up with a verve all their own.

Above: Loren Aragon designs for the powerful millennial woman acting as a CEO or entrepreneur.

“A big part of fashion design in the mainstream has been generalized versions of Native culture—fringe, feathers, and war bonnets,” Aragon says. “But not all Native Americans have those as part of their culture.” He says he stays away from stereotypes and tries to inspire other designers through his example to tell stories based on their own cultures. Even as Aragon and other Native designers join the larger fashion world, they’re still distinctive. “I like how it stands out,” Aragon says. “We don’t want traditional garments to be the limit. We want it to be enjoyed by everybody, every day.”

His company, ACONAV, combines his Acoma Pueblo heritage with that of his wife, Valentina, a Navajo (Diné) who also serves as his operations manager. Visually, Aragon’s designs echo the black-and-white pottery for which his pueblo is renowned. ACONAV traces Diné influences more subtly. The culture’s matrilineal heritage inspires Aragon’s “girl”—the person he imagines designing for—whom he visualizes as a powerful millennial woman acting as a CEO or entrepreneur. Diné culture also teaches that living people represent their ancestors in this world, so those who dress to reflect their heritage are making their ancestors proud.

Above: Aragon's dresses are inspired by traditional Acoma pottery. Models showcase new works at the Native American Clothing Contest during this year's Santa Fe Indian Market.

These overt cultural ties—and Aragon’s seamless interpretation of them—drew attention from Phoenix Fashion Week, where he won the 2018 Couture Designer of the Year Award, and from Disney executives. Partnering with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and Santa Fe’s Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Disney opened Creating Tradition: Innovation and Change in American Indian Art at Florida’s Epcot theme park in July. They commissioned Aragon to create a dress for the exhibition—he was one of only three U.S. artists of any medium to receive that invitation. Disney directed Aragon to seek design inspiration in the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture’s archives. He landed on a traditional, early-1900s olla with a black-on-white design and a terra-cotta interior. The resulting “Ancient Resonance” dress reflects the vessel’s color with white silk and a terra-cotta lining. A hand-cut black leather overlay translates the pot’s graphic pattern in a modern way. The dress echoes the olla’s rounded form with structured cap sleeves, a mock turtleneck, and a double fluted skirt.

Above: "When you're hearing prayers, it's a holy experience that transports your from where you are. I hope these designs transport you as well," says Orlando Dugi.

Acoma Pueblo’s pottery is Aragon’s creative well, but he takes the art beyond clay. “I wanted to show the importance of preserving our culture through different mediums,” he says, smiling above his soul patch and wearing spiked hoop earrings along with his own buffalo-design T-shirt. “I wanted to stimulate the youth to expand and not just be a pottery culture, to take what we know to be our traditional art and to present it in a more creative way.”

Aragon moved to Arizona in 1998 to pursue an engineering degree. He left that career behind for full-time design in 2016. The Phoenix-based designer says the two fields aren’t as different as one might expect. Even while an engineer, Aragon dabbled in illustration, sculpture, and jewelry. As he observed his fellow Native artists, he realized that clothing was a nearly unexplored niche, a way to take a creative stand. The only problem: He had no experience in fashion design or garment construction. He taught himself by dismantling dresses and reverse-engineering them. He also had a little help from his seamstress mother and YouTube videos. To infuse the garments with Acoma style, he began painting fabric by hand, then producing his own textiles. He bases many of his textile patterns on traditional pottery designs, from a parrot pattern to one of a dragonfly. One of his most popular textile and T-shirt designs is based on an image of shattered pottery pieces. “In our culture, broken pottery isn’t bad—it’s just the beginning,” he says.

Those textiles birthed his fashion career. He’s since shown at Denver’s Native Fashion in the City and at PLITZS New York City Fashion Week. Indigenous actresses Tinsel Korey and Grace Dove have worn his designs at red-carpet events. And he’s earned art fellowships at the School for Advanced Research, in 2017, and the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, in 2012. Perhaps his splashiest showing, outside of Epcot, was at the 2017 Phoenix Fashion Week. His pueblo’s emergence story inspired the collection. Models strutted down the runway in swirling dresses of the deepest eggplant and black, recalling the stories of his people rising out of darkness. An elegant rainbow gown captured every hue, and the collection’s single white dress rippled playfully with ruffles inspired by a pinch pot. The dresses were at home on the runway and still purely Acoma/Diné.

Above: "I was artistic from the time I was born to the earth," says Michelle Tsosie Sisneros, who now focuses on painting shoes.

LOREN ARAGON DESIGNS ARE NEWER to Native American fashion runways, but even longtime designers are inspired by Patricia Michaels’ success and the design renaissance. For some, like Santa Fe–based Diné designer Orlando Dugi, heritage is ever present, though less visually explicit.

Dugi was a Santa Fe Indian Market regular for several years and opened his own City Different atelier in 2013, but he has been publicly absent since his shop closed in 2016. He spent the time studying fashion design at Santa Fe Community College and completing the same Phoenix Fashion Week boot camp that catapulted Aragon’s career. With a rebooted brand and the fall 2018 launch of his ready-to-wear line, the Diné designer’s clothes are available once again—this time online and through yet-to-be-named boutiques.

Although Dugi’s creativity flowed into the creation of accessories and custom gowns, finding buyers for those items either in his store or online was a struggle. He, like other Native fashion designers, was competing against fast fashion, at one end of the spectrum, and established, big-name design houses at the other. He hopes his new production and marketing knowledge will help him turn his previously haute couture fashion brand into a ready-to-wear line.

Although Dugi will no longer hand-stitch every garment, each will still bear design hallmarks inspired by his childhood in Gray Mountain, Arizona. He recalls ceremony days on the reservation, when women would turn out in their luxurious velvet blouses and skirts, intricate jewelry, and perfectly coiffed hair. Young Dugi found it glamorous, so when he began to sketch dresses a decade ago, he leaned into haute couture. By then he was living away from the small reservation town where he’d grown up and had seen high-end designers’ creations in glossy fashion magazines. He’d spotted Judith Leiber’s fantastical beaded clutches in shapes like cupcakes and unicorns, though he observed that the beads were glued on—a lesser art for someone who grew up sewing beads with his grandmother and father. So he started making his own versions and selling them at Native art markets. He added Yves Saint Laurent–inspired ear pendants. Soon his pieces were featured during Indian Market’s Native American Clothing Contest, where he won first place in the contemporary category in 2011.

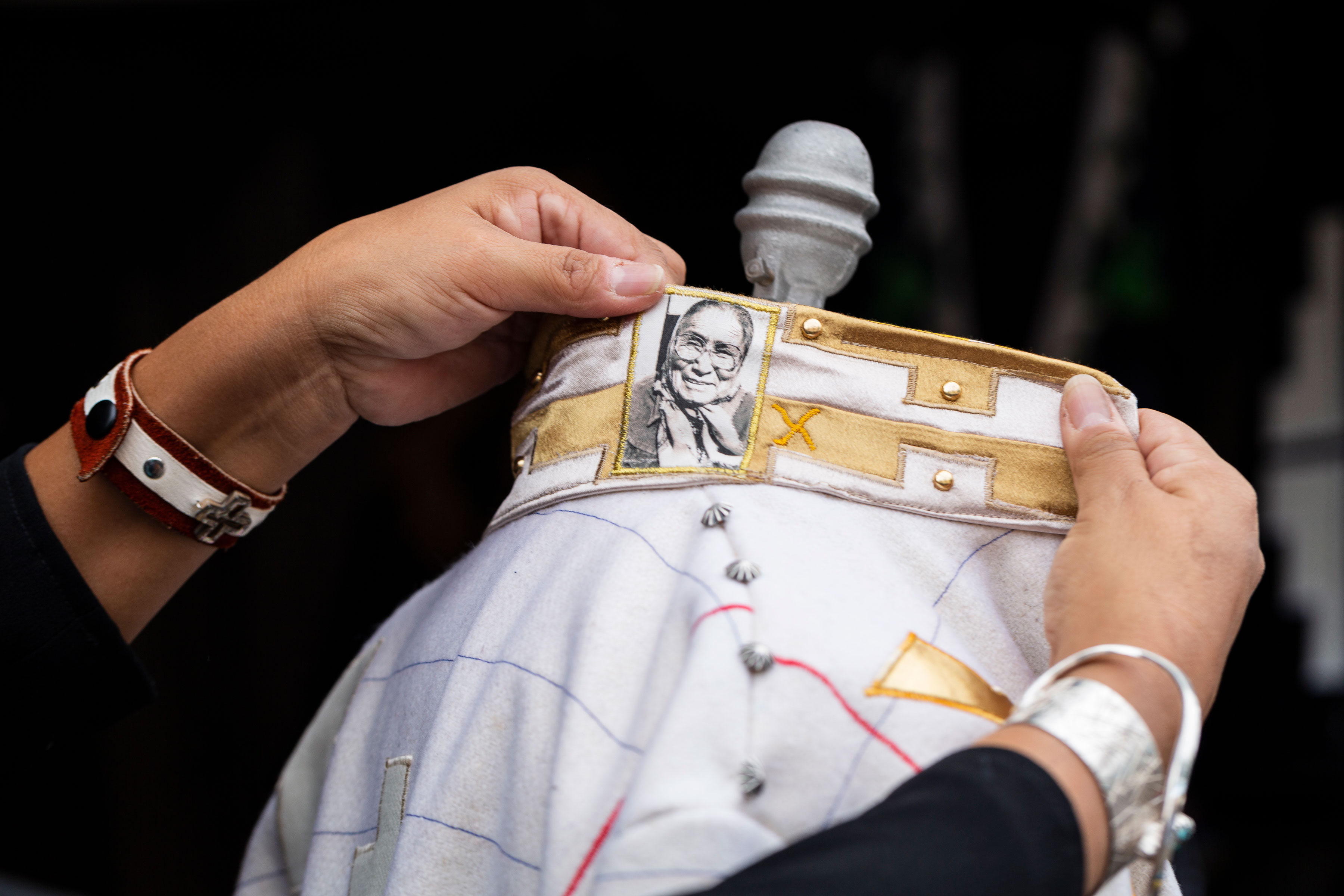

Above: Penny Singer is known for her appliqués, like the one below with a photo of her grandparents on the Navajo reservation.

“The influence of Native culture is not literal for me,” he says. His memories of tribal ceremonies influenced his work. He recalls the ceremonies as transcendent experiences that carried him out of the earthly plane and he aims for his designs to do the same. For much of his career, his dresses have been for galas and red-carpet occasions—events far from the everyday. “When you’re hearing prayers, it’s a holy experience that transports you from where you are. I hope these designs transport you as well,” he says. There are more concrete influences, too: Many of his people’s ceremonies take place at night, beneath glittering stars. Under Dugi’s sewing needle, that experience translates into intricately beaded crystals and rhinestones.

His new collection, which was slated to debut at Phoenix Fashion Week in October, was signature Orlando Dugi, with a few new patterns. The structured designs simmered in slate gray, with touches of berry and pink, and intricate details like fabric pleating, sparkling beadwork, embroidery, or fluffy feathers (finishings more typical of designers like Valentino or Carolina Herrera than Native American regalia). Models strutted down the runway in pants and tops he’d designed, not just gowns. Selling separates, combined with his new hands-off approach, means his designs will be more affordable, running $500–$5,000—a move he hopes will make his work more accessible and profitable, too.

SEVERAL NATIVE AMERICAN DESIGNERS focus exclusively on everyday fashions like tees and sneakers. Like Dugi, Albuquerque-based Diné designer Penny Singer has been a staple at Santa Fe Indian Market and other art markets for more than a decade. With her son out of school, the single mom says she hopes to expand her brand.

Singer’s design career began when she was attending Haskell Indian Nations University, in Lawrence, Kansas, where she sewed Southern Plains dance regalia for fellow students. She transferred to Santa Fe’s Institute of American Indian Arts in 1992 to study photography and documentary film. After graduating in 1995, the self-taught designer felt drawn back to fashion design, and showed her first pieces at Indian Market in 1999. She earned a 2007 fellowship from the market and has remained a Santa Fe Indian Market regular.

Read more: 5 Can't Miss Native Restaurants.

Her signature ribbon shirts—men’s broadcloth tops detailed with ribbons across the chest, back, and sleeves—have found Native and non-Native fans alike. Over time, she’s created purses, pillows, and bow ties. She designs wearable art to complement modern clothes. While not always identifiably Diné, the creations are always distinguishably Singer. “I like very bold designs,” says the artist, who on this day is wearing turquoise sunglasses and a beaded bracelet with Star Wars Stormtroopers.

Above: Cody St. Arnold designs and prints concert-inspired T-shirts.

Although Singer has often fashioned coats made of broadcloth—eye-catching for their striking white, black, and red geometric patterns—she narrowed her vision for her fall 2018 collection. Diné Life, which is available via her website and by calling the artist, features appliqués—fabric stitched onto a garment—of hogans and sheep on jackets. Appliqués of Navajo Nation landmarks appear on handbags. For Singer, it feels like getting back to her roots, connecting with both her culture and her artistic training. “I’m putting more documentary in my work,” she says.

Albuquerque resident Cody St. Arnold also bases his T-shirt designs on cultural symbols, though his are from his Jicarilla Apache heritage. St. Arnold fell in love with printmaking during a 2010 class at the University of Colorado. Although he had the technical knowledge, it wasn’t until a Boulder screen-printing shop showed him that T-shirts could be a viable business that he began printing concert-inspired tees. He bought his first four-color press in 2013 and has been printing ever since. “People liked having wearable artwork,” he says. He blends a rock-show vibe with Native influences. Just as carved stone animal fetishes are thought to harness the power of that creature, St. Arnold sees animal imagery on T-shirts as a way to bring their energy to the wearer. With a California eighties aesthetic and repeating Southwestern patterns, his Bear design reflects the animal’s strength and protective powers. On his Good Luck design, St. Arnold depicts a circle of horny toads, a symbol of luck to the Jicarilla Apache.

Pueblo imagery is front and center on Michelle Tsosie Sisneros’ painted shoes. “I was artistic from the time I was born to the earth,” Sisneros says. No wonder: Her aunt was renowned Santa Clara Pueblo painter Pablita Velarde. “She really motivated me and planted the seeds for me to follow in her footsteps,” she says. Though Sisneros harbored a love for fashion design, she leaned into painting, a more stable career choice. A few years ago, she found a new canvas: Converse shoes. She’s since expanded to children’s shoes, and leather ankle boots, sandals, and high heels for adults. She paints abstractions of eagle feathers, bear footprints, turtles, and other Native symbols that reflect her combined Santa Clara Pueblo, Diné, and Laguna Pueblo roots. “One thing I’m careful with is to be very respectful of the heritage I come from. I don’t paint anything ceremonial, like katsinas. I don’t want to disrespect what I’ve been taught,” she says. Her shoes were available at the Museum of Arts and Culture in conjunction with the exhibit Stepping Out: 10,000 Years of Walking the West and can be found at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center shop. However, she sells mostly through her Facebook page, where she’s able to share directly with customers. Someone usually snaps up her designs as soon as she posts a picture. The Santa Clara Pueblo–based artist has also spread her wings into accessories, including silk scarves for which she painted the design, and a beaded butterfly bag available in the Smithsonian museums’ spring 2018 catalog.

Sisneros has observed Native American fashion design over the years and has witnessed the Patricia Michaels effect. “She struggled a lot, no doubt, but she pushed forward,” she says. “To put yourself out there in a dog-eat-dog world speaks volumes about who she is as a person and the passion she has about her artwork. She’s the trailblazer of her generation. She opened the door for artists to get out there and do what they want to do.”

LEARN MORE

- ACONAV

- Orlando Dugi

- Cody St. Arnold: The Octopus and the Fox and Spur Line Supply Co., both in Albuquerque, as well as the site, codysaintarnold.com

- Michelle Tsosie Sisneros: On her Facebook page

- Penny Singer